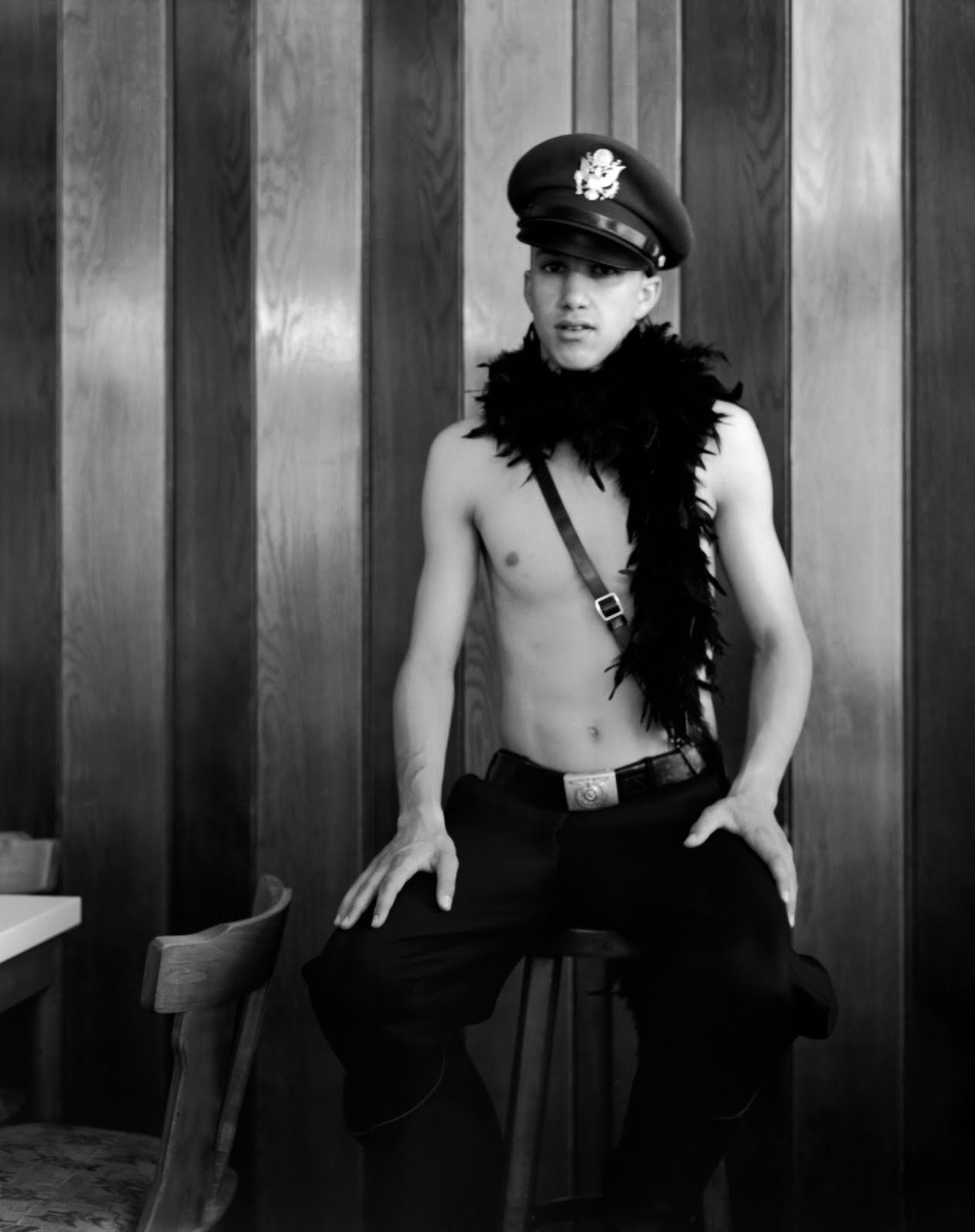

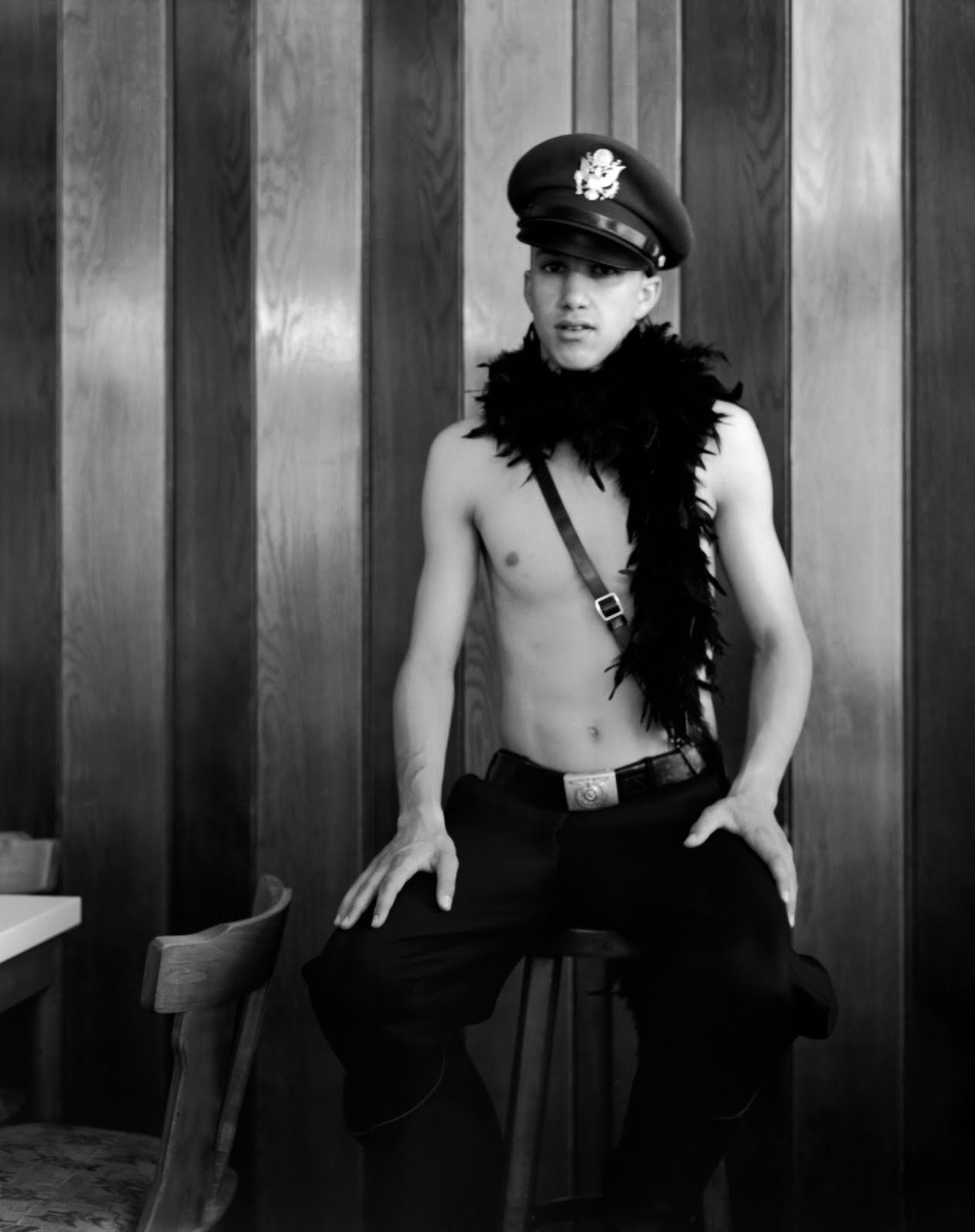

artwork by Collier Schorr

[On October 11, 2010 the Unit for Criticism and the Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studies Initiative hosted "The Killer in Me is the Killer in You: Homosexuality and Fascism," a lecture by Judith Halberstam of the University of Southern California.]

Judith Halberstam’s “The Killer in Me is the Killer in You: Homosexuality and Fascism”

Written by Chase Dimock (Comparative & World Literature)

Beyond merely cataloguing homosexuality’s flirtations with fascist politics and iconography, Judith Halberstam’s lecture sought to question the very core of historical research in queer studies by asking “how do we do or not do gay history?” For Halberstam, the key question is: what parts of queer history we ignore or leave uninvestigated because of political inconvenience, or because we wish to repress certain objectionable past practices from consciousness.

Beyond merely cataloguing homosexuality’s flirtations with fascist politics and iconography, Judith Halberstam’s lecture sought to question the very core of historical research in queer studies by asking “how do we do or not do gay history?” For Halberstam, the key question is: what parts of queer history we ignore or leave uninvestigated because of political inconvenience, or because we wish to repress certain objectionable past practices from consciousness.

Calling upon George Chauncey’s notion of queer history as a “repressed archive”, Halberstam argued that while queer scholarship has often uncovered narratives that had remained buried in the back of the closet, it has also tended only to pull from that closet the voices and histories that support an unquestioned progress narrative of queer culture. The skeletons that do not please the historian remain closeted.

Halberstam appealed against this logic of selective history, arguing that this vision of queer history has painted a distorted picture of the 20th century in which gays and lesbians are portrayed as perpetual victims of a universal, culturally unspecific homophobia. Instead, Halberstam proposed that we pay more attention to the history of gay collaboration with the production of fascist ideology and imagery while stating that the goal should not be to settle the issue on one correct history, but to explore “the ethics of complicity” with fascism alongside other narratives.

Halberstam located homosexuality’s complicity with fascism in the politics of Nazi Germany and its afterlife in Nazi iconography and the contemporary politics of equating modern causes with the Holocaust. Halberstam argued against the notion that in order to prove homosexuality’s collusion with Nazi Germany, one must cite examples of openly homosexual Nazi leaders (of which only one example, Ernst Roehm is typically given). Instead, she argued that the most important role homosexuality played in German culture in the 1920s and ‘30s was in its parallel valorization of virile masculinity and the promotion of homosocial bonds with men, setting a precedent for the imagery and discourse of masculine superiority and gender-exclusive social programs employed by the Nazi party. While homosexuality remained prohibited under an 1871 law (known as “Paragraph 175”) and while the Nazi party did not encourage homosexual relationships among its corps, the encouragement of intense male bonding, which sometimes spilled over into homosexual activity, allowed for a cohesion amongst Nazi men which strengthened the Nazi war machine.

While homosexuality remained prohibited under an 1871 law (known as “Paragraph 175”) and while the Nazi party did not encourage homosexual relationships among its corps, the encouragement of intense male bonding, which sometimes spilled over into homosexual activity, allowed for a cohesion amongst Nazi men which strengthened the Nazi war machine.

Halberstam traced this genealogy to the often-overlooked works of Hans Bluher and Adolf Brand and their promotion of the “Masculinism movement” within 1920s German gay liberation. Whereas the famous German sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld promoted the notion of “inversion” to conceptualize homosexuality as an innate reversal of gender traits, the masculinists resisted biological causes and championed a culturalist notion of the superior masculinity of homosexual men. They envisioned a structure of homosexual relations in which neither man played the role of a woman and the influence of femininity would be completely eliminated. Halberstam argued that the glorification of masculinity which Bluher and Brand encouraged in the men’s groups (Männerbünde) helped to inform the Nazis’ formation of tightly knit men’s groups along comparable lines. In fact, in many young men’s minds, the two groups were virtually indistinguishable. Despite the overt interdiction against homosexuality in their ranks, the Nazi Party appealed to many homosexual men whose vision of masculinity corresponded to that of the Nazi Party. Thus, many became complicit in the Nazi Party’s crimes.

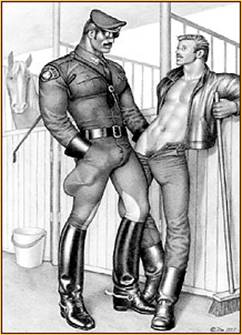

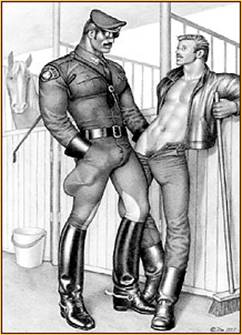

Halberstam devoted equal time to a consideration of the erotic afterlife of homosexuality’s relationship with fascism. Her focus on the appropriation of Nazi imagery in the visual arts included the drawings of Tom of Finland, the paintings of Richard Lukas, and the photography of Collier Schorr. In discussing the works of Tom of Finland (see image right), whose experience with Finnish Army and Nazi soldiers inspired his erotic drawings, Halberstam recalled a contentious moment with another scholar who opposed the idea that an erotic attraction to the cartoons featuring exaggeratedly muscled nude SS men and Nazi soldiers indicated any endorsement of political ideology. While Halberstam made it clear she was not accusing Tom of Finland or the defensive scholar of promoting Nazi politics, she was quick to criticize a concept of the erotic which attempts to deny the political meanings of the images that it appropriates.

Halberstam devoted equal time to a consideration of the erotic afterlife of homosexuality’s relationship with fascism. Her focus on the appropriation of Nazi imagery in the visual arts included the drawings of Tom of Finland, the paintings of Richard Lukas, and the photography of Collier Schorr. In discussing the works of Tom of Finland (see image right), whose experience with Finnish Army and Nazi soldiers inspired his erotic drawings, Halberstam recalled a contentious moment with another scholar who opposed the idea that an erotic attraction to the cartoons featuring exaggeratedly muscled nude SS men and Nazi soldiers indicated any endorsement of political ideology. While Halberstam made it clear she was not accusing Tom of Finland or the defensive scholar of promoting Nazi politics, she was quick to criticize a concept of the erotic which attempts to deny the political meanings of the images that it appropriates.

Ultimately, this refusal to acknowledge a relationship between the erotic and the political represents another site of repression in queer studies where the opportunity to explore and learn more about how queer sexuality fetishizes relations of power is condemned due to fear of what may be found hidden in the closet.

Halberstam lauded the works of Lukas (see image right) and Schorr as ethical in their unflinching portrayal of erotic male bodies either dressed in or situated around Nazi imagery. As visual artists, Schorr and Lukas create works that perform a similar function to Halberstam’s scholarship: an endeavor to not settle the score or let any segment of the queer community off the hook for the life and afterlife of fascism. Instead, they continue to raise questions and to map the various intersections of homosexuality and fascism in history and in the future.

Halberstam lauded the works of Lukas (see image right) and Schorr as ethical in their unflinching portrayal of erotic male bodies either dressed in or situated around Nazi imagery. As visual artists, Schorr and Lukas create works that perform a similar function to Halberstam’s scholarship: an endeavor to not settle the score or let any segment of the queer community off the hook for the life and afterlife of fascism. Instead, they continue to raise questions and to map the various intersections of homosexuality and fascism in history and in the future.

[On October 11, 2010 the Unit for Criticism and the Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studies Initiative hosted "The Killer in Me is the Killer in You: Homosexuality and Fascism," a lecture by Judith Halberstam of the University of Southern California.]

Judith Halberstam’s “The Killer in Me is the Killer in You: Homosexuality and Fascism”

Written by Chase Dimock (Comparative & World Literature)

Beyond merely cataloguing homosexuality’s flirtations with fascist politics and iconography, Judith Halberstam’s lecture sought to question the very core of historical research in queer studies by asking “how do we do or not do gay history?” For Halberstam, the key question is: what parts of queer history we ignore or leave uninvestigated because of political inconvenience, or because we wish to repress certain objectionable past practices from consciousness.

Beyond merely cataloguing homosexuality’s flirtations with fascist politics and iconography, Judith Halberstam’s lecture sought to question the very core of historical research in queer studies by asking “how do we do or not do gay history?” For Halberstam, the key question is: what parts of queer history we ignore or leave uninvestigated because of political inconvenience, or because we wish to repress certain objectionable past practices from consciousness.Calling upon George Chauncey’s notion of queer history as a “repressed archive”, Halberstam argued that while queer scholarship has often uncovered narratives that had remained buried in the back of the closet, it has also tended only to pull from that closet the voices and histories that support an unquestioned progress narrative of queer culture. The skeletons that do not please the historian remain closeted.

Halberstam appealed against this logic of selective history, arguing that this vision of queer history has painted a distorted picture of the 20th century in which gays and lesbians are portrayed as perpetual victims of a universal, culturally unspecific homophobia. Instead, Halberstam proposed that we pay more attention to the history of gay collaboration with the production of fascist ideology and imagery while stating that the goal should not be to settle the issue on one correct history, but to explore “the ethics of complicity” with fascism alongside other narratives.

Halberstam located homosexuality’s complicity with fascism in the politics of Nazi Germany and its afterlife in Nazi iconography and the contemporary politics of equating modern causes with the Holocaust. Halberstam argued against the notion that in order to prove homosexuality’s collusion with Nazi Germany, one must cite examples of openly homosexual Nazi leaders (of which only one example, Ernst Roehm is typically given). Instead, she argued that the most important role homosexuality played in German culture in the 1920s and ‘30s was in its parallel valorization of virile masculinity and the promotion of homosocial bonds with men, setting a precedent for the imagery and discourse of masculine superiority and gender-exclusive social programs employed by the Nazi party.

While homosexuality remained prohibited under an 1871 law (known as “Paragraph 175”) and while the Nazi party did not encourage homosexual relationships among its corps, the encouragement of intense male bonding, which sometimes spilled over into homosexual activity, allowed for a cohesion amongst Nazi men which strengthened the Nazi war machine.

While homosexuality remained prohibited under an 1871 law (known as “Paragraph 175”) and while the Nazi party did not encourage homosexual relationships among its corps, the encouragement of intense male bonding, which sometimes spilled over into homosexual activity, allowed for a cohesion amongst Nazi men which strengthened the Nazi war machine.Halberstam traced this genealogy to the often-overlooked works of Hans Bluher and Adolf Brand and their promotion of the “Masculinism movement” within 1920s German gay liberation. Whereas the famous German sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld promoted the notion of “inversion” to conceptualize homosexuality as an innate reversal of gender traits, the masculinists resisted biological causes and championed a culturalist notion of the superior masculinity of homosexual men. They envisioned a structure of homosexual relations in which neither man played the role of a woman and the influence of femininity would be completely eliminated. Halberstam argued that the glorification of masculinity which Bluher and Brand encouraged in the men’s groups (Männerbünde) helped to inform the Nazis’ formation of tightly knit men’s groups along comparable lines. In fact, in many young men’s minds, the two groups were virtually indistinguishable. Despite the overt interdiction against homosexuality in their ranks, the Nazi Party appealed to many homosexual men whose vision of masculinity corresponded to that of the Nazi Party. Thus, many became complicit in the Nazi Party’s crimes.

Halberstam devoted equal time to a consideration of the erotic afterlife of homosexuality’s relationship with fascism. Her focus on the appropriation of Nazi imagery in the visual arts included the drawings of Tom of Finland, the paintings of Richard Lukas, and the photography of Collier Schorr. In discussing the works of Tom of Finland (see image right), whose experience with Finnish Army and Nazi soldiers inspired his erotic drawings, Halberstam recalled a contentious moment with another scholar who opposed the idea that an erotic attraction to the cartoons featuring exaggeratedly muscled nude SS men and Nazi soldiers indicated any endorsement of political ideology. While Halberstam made it clear she was not accusing Tom of Finland or the defensive scholar of promoting Nazi politics, she was quick to criticize a concept of the erotic which attempts to deny the political meanings of the images that it appropriates.

Halberstam devoted equal time to a consideration of the erotic afterlife of homosexuality’s relationship with fascism. Her focus on the appropriation of Nazi imagery in the visual arts included the drawings of Tom of Finland, the paintings of Richard Lukas, and the photography of Collier Schorr. In discussing the works of Tom of Finland (see image right), whose experience with Finnish Army and Nazi soldiers inspired his erotic drawings, Halberstam recalled a contentious moment with another scholar who opposed the idea that an erotic attraction to the cartoons featuring exaggeratedly muscled nude SS men and Nazi soldiers indicated any endorsement of political ideology. While Halberstam made it clear she was not accusing Tom of Finland or the defensive scholar of promoting Nazi politics, she was quick to criticize a concept of the erotic which attempts to deny the political meanings of the images that it appropriates.Ultimately, this refusal to acknowledge a relationship between the erotic and the political represents another site of repression in queer studies where the opportunity to explore and learn more about how queer sexuality fetishizes relations of power is condemned due to fear of what may be found hidden in the closet.

Halberstam lauded the works of Lukas (see image right) and Schorr as ethical in their unflinching portrayal of erotic male bodies either dressed in or situated around Nazi imagery. As visual artists, Schorr and Lukas create works that perform a similar function to Halberstam’s scholarship: an endeavor to not settle the score or let any segment of the queer community off the hook for the life and afterlife of fascism. Instead, they continue to raise questions and to map the various intersections of homosexuality and fascism in history and in the future.

Halberstam lauded the works of Lukas (see image right) and Schorr as ethical in their unflinching portrayal of erotic male bodies either dressed in or situated around Nazi imagery. As visual artists, Schorr and Lukas create works that perform a similar function to Halberstam’s scholarship: an endeavor to not settle the score or let any segment of the queer community off the hook for the life and afterlife of fascism. Instead, they continue to raise questions and to map the various intersections of homosexuality and fascism in history and in the future.