On October 17, 2023, Professor Tamara Chaplin (History UIUC) presented her talk “Queering French History” as part of the Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory’s Modern Critical Theory lecture series.

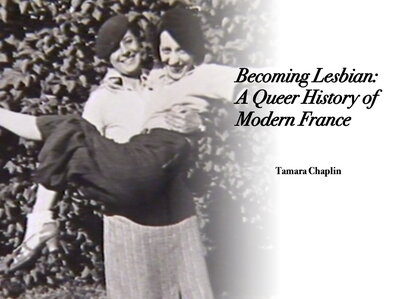

“How do I name the queer past?” This is a question Tamara Chaplin grapples with throughout her book Becoming Lesbian: A Queer History of Modern France. In her Modern Critical Theory (MCT) lecture, Chaplin demonstrated how queer theory has informed her work as a historian.

To begin uncovering how one might write a queer history of the past, Chaplin engaged the MCT audience in critical questioning. She asked the audience what they thought when considering a definition of queer. After one audience member astutely offered that queerness is what is counter to the normative, Chaplin continued to dig into what Laura Doan refers to as the “vex[ing]” definition of queer. Historically, queer has taken on many meanings, such as “odd” or “strange” behavior, a slur for LGBTQIA+ individuals, or a reclamation of one’s own gender/sexual identity. As Chaplin puts it, queerness, when taken as a critical approach, “seeks to make visible the invisible work of the institutions, structures, practices and people that reinforce … the privileges granted [to] heterosexuality and gender normativity in the social world.” Queer theory has often been used as a method of dismantling gender and sexuality norms; however, in thinking with Kimberlé W. Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality, queer theory is not exclusive to gender and sexuality but engages with race, class, ability, nation, religion, etc. as mutually constitutive identities. In queer theory, queerness is often thought of as a verb, a doing, that allows us to think about how “dominant groups or individuals” exert power over “marginalized others.” So, how then does one begin to queer history?

To do this, Chaplin focuses on four main tenets:

- “Pay attention to the historicity of language and to the etymologies of desire.”

- “When evidence permits, convey how individuals understood their own erotic inclinations and gender performances.”

- “Define terms, justify labels.”

- “Frame my questions within the parameters of queer critical argument.”

Chaplin considers how her subjects identified themselves, given the contexts in which they lived, and acknowledges the constraints posed by discrepancies between contemporary and historical language. Specifically, she recognizes that her subjects might have not labeled themselves as “lesbian” due to cultural implications. As a research method, Chaplin pays close attention to how her subjects identify and talk about themselves to different audiences, but because of the constricted nature of the archive, this can sometimes result in contradictory answers or limited information. Furthermore, Chaplin chooses to write about her subjects as “women,” accepting binary gender categories that were employed during the time period in which she writes. Chaplin argues for pronoun uses that follow historical connotations while still being aware that some of her subjects might have identified as trans today. Trying to fix a singular identity for these subjects is not Chaplin’s goal; instead, she focuses on what their lives and the navigation of their desires can tell us about a particular social and political moment.

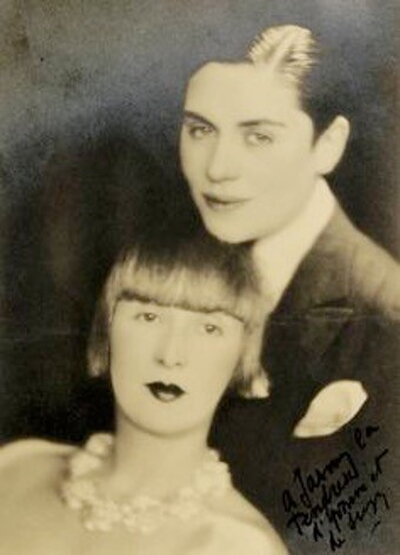

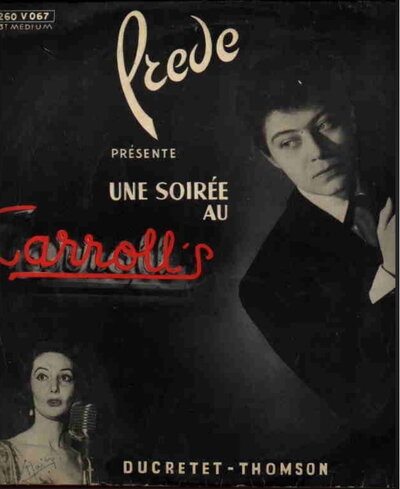

As opposed to “recovery history,” a practice Doan describes as relying on contemporary knowledges to revise past histories to create a stable sense of identity across time, Chaplin provides a queer perspective of historical France by highlighting the lesbian French social scene in the 20th century. Becoming Lesbian draws upon 100 interviews with French lesbian women together with sources found in public and private archives, relying especially on the archives of cabaret workers, Frede and Suzy Solidor. Both of these La Vie Parisienne/Le Carroll’s icons fluctuated in gender and sexual identity over the course of their lives: Frede adopted a gender-neutral name, presented as masculine, and took a woman partner, while Solidor oscillated between masculine and feminine presentation and lovers. Through their active role in the cabaret scene, Frede and Solidor became fixtures in the French lesbian scene and international lesbian culture, providing visibility that helped shape political and social life in 20th century France.

Bottom: an album cover featuring Frede and partner Miki Leff at Le Carroll's in 1956. These photos were provided courtesy of Chaplin and were displayed in her talk.)

Because the French State positions the citizen subject as “universal,” identity markers—such as race, gender, and sexuality—are relegated to the private sphere. This separation of public and private is almost always used to impose violence upon the marginalized. In her talk, Chaplin argued that media helped serve as a bridge between public and private life: “The Sapphic subcultures established in Paris … survived [WWII] and laid the groundwork for the collective construction and politicization of lesbian identity in the decades that followed.” Whether it was magazines dubbing Frede as the “most famous lesbian in the world” or Suzy Solidor becoming the first (queer) singer to be broadcast on French television in 1935, lesbian visibility queered the public sphere and, thus, worked to change public opinion. Though French archives grievously silence the queer identification of Frede and Solidor’s lives, Chaplin’s work situates French lesbian life at the center of 20th century French history by foregrounding how her subjects navigated sexuality and gender performance.

Chaplin concluded her talk with three final claims:

- “Lesbian history matters—not simply for what it tells us about other things but because the experiences of women who desire women … matter.”

- “Becoming Lesbian insists that, due to the double-domination that lesbians of all colors experience as both women and as sexual minorities, lesbian history cannot be subsumed within either histories of feminism, histories of homosexuality, or of queer histories more broadly.”

- “By revealing lesbian identity as a process of becoming, my work demonstrates that sexual desire is a living construct that waxes and wanes across time and place, even over the lifetime of a single individual.”

Chaplin’s lecture shed light on queer expressions of gender and sexuality that had been silenced by history and argued for that which was deemed private to become public. By highlighting these lesbian histories, Chaplin makes for a more authentic picture of the past—one that decenters the heteronormativity of history and illuminates the queerness that was always already there.