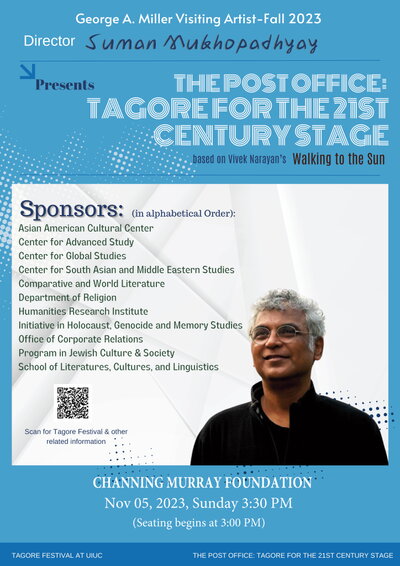

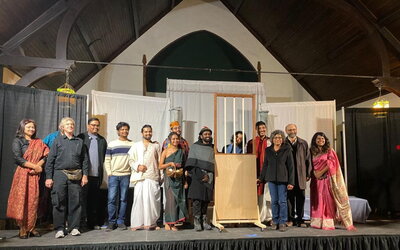

On November 5, 2023, as a part of the XXXII Annual Tagore Festival, the acclaimed thespian and film director Suman Mukhopadhyay, hosted by the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, as this semester’s George A Miller Visiting Artist, staged a play titled The Post Office: Tagore for the 21st Century Stage at the Channing Murray Foundation. The production was initially scheduled for the evening of October 28 at Lincoln Hall Theater. The cast and crew comprised a group of graduate students and members of the faculty across several disciplines. The performance was packed with a full audience.

At the onset of the program, Professor Rini Bhattacharya Mehta highlighted the historic importance of the Channing Murray Foundation in the context of Rabindranath Tagore’s stay in Urbana-Champaign. He had delivered his first lecture in the United States at the vestiges of that foundation when he came to visit his son, Rathindranath Tagore, an alumnus of the Department of Agriculture, more than a hundred years ago in 1912. Ragini Chakraborty, a doctoral candidate in Comparative Literature, who anchored the event, pointed out that The Post Office was written in the same year.

In this production, Mukhopadhyay brought together extracts from an English translation of The Post Office and Vivek Narayan’s Hindi play Walking to the Sun which recounted how the Polish physician, Dr Korczak (acted in parts by Professor Pratik Banerjee and Diptarko Saha) produced Tagore’s play with children from an orphanage in a Jewish ghetto in Nazi-occupied Warsaw in 1942. Clips from the 1990 film Korczak (directed by Andrzej Wajda) were also juxtaposed into the multimodal narrative of the performance.

Tagore’s 1912 play revolved around an ailing orphan child Amal quarantined in his uncle’s living room in their final days. Portraying him as a metaphor for innocence in their interactions with the outer world in this allegorical text, Tagore made a statement about how virtue, despite its occasional childlike naivety, has the power to transform the vile and the heinous. Amal does not survive; nor does the sanity of the world that went to war within a couple of years. In this adaptation, Mukhopadhyay consciously cast a female actor (Geetanjali Gera, who delivered a scintillating performance) for Amal, whom Tagore had conceived as a biological male, to dissolve gender binaries and emphasize the androgynous, almost universal claim of the character’s innocence. This was also a subtle reversal of the long tradition of the Bengali stage that debarred genteel society women from participating in theater. Female roles were often assigned to pre-adolescent males.

The Post Office speaks to a twenty-first-century American campus crowd at a moment when some parts of the globe are marred again with colonialist aggression, genocide, ethnic cleansing, and bloodshed. To achieve an amalgamation of three distinct texts, Mukhopadhyay used three projection screens to split the stage. While one part was dedicated to the unfolding of Korczak’s tale, the other segment hosted extracts from the original play. The only mobile object was a window on wheels, placed almost at the center of the action. The dreamy Amal, enchanted with the beauty of their surroundings and people, swayed on that swinging window and mused on their childlike reveries. The underlying symbolism of Amal’s free movement across the partitioned stage can be unpacked as the liberating force of imagination as it wrestles against the stagnancy of physical and mental confinement. Although the presence of too many props cramped the little performative space offered at Channing Murray, leaving hardly any room for the actors to move freely without tripping, such a claustrophobic setting could also be a conscious reminder of the ghastly circumstances of the Holocaust.

Several songs were interspersed in the narrative. While most of these were written and put to music by Tagore (and rendered by Nibedita Chakraborty, Arghya Chakraborty, Tanmoy Debnath, and Prasad Packirisamy), there was also a recording of the legendary Polish protest song Siekiera Motyka, popularized during World War II. Tagore’s composition of a Vedic verse from the Upanishads (“Shrinwantu Vishwe Amritasya Putra”/Listen, ye immortal children of the world), a testament to his indefatigable conviction in humanity, was accommodated near the end of the play. In this way, the production strung together a Bengali play, a Polish film, a Sanskrit prayer, and a Hindi play along with their relevant English translations to enhance Tagore’s tryst with universal humanism for a multilingual and international audience.

In a 1907 lecture titled Vishva Sahitya, Tagore moved away from Goethe’s conceptualization of world literature as a tallying of various national literatures to posit that literature by its very definition belonged to the world. He argued, “So what does literature acquaint us with? With humanity’s wealth and abundance, which overflows all its material needs and is not exhausted within its mundane limits”. To bolster the “wealth and abundance” of the universality of innocence across the “mundane limits” of time, Tagore deliberately abstained from filling the Post Office with temporal allusions, thereby emphasizing the play’s universal allegory. This results in making the text available for adaptations across national boundaries, relatively free of cultural specificities. For this reason, it was not strange that Dr Korczak could relate to the death of innocence embodied by the precarity of an ailing child while working in an orphanage in wartime Poland. Nor is it hard for us to find reverberations of what Tagore tried to imply as we contemplate the thousands of infants and children killed by advanced weapons of mass destruction in current and ongoing massacres.

Milan Kundera famously wrote in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting (1979) that “the struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting”. By stitching together the fragments shored against the ruins of the Holocaust with that of colonial India, Mukhopadhyay tacitly reminds us that though the identities of the oppressor and the oppressed might alter across time and space, the transformative potential of innocence to redeem humanity of its sins is more pertinent than ever.