On October 29, 2024, Tithi Bhattacharya, a professor of History at Purdue University, delivered a lecture for the Unit for Criticism’s Modern Critical Theory Lecture series. This lecture followed her talk at the Channing-Murray Center earlier in the day, and a graduate student reading group on October 28th. The lecture centered on Bhattacharya’s new book Ghostly Past, Capitalist Presence, which examines tales of ghostly beings in Bengal, asking what they can tell us about past politics and ideologies. She suggests that ghosts illuminate the “backways and alleyways” of political history and show how historical hauntings reveal the workings of capitalist modernity.

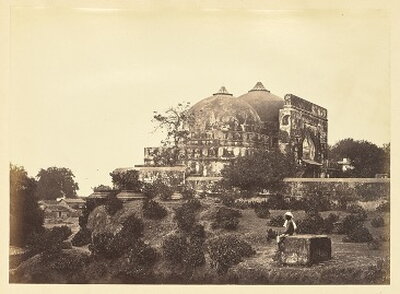

Bhattacharya set a somber tone at the beginning of her lecture, acknowledging ongoing crises, such as the current genocide in Palestine, and questioning the role of researchers in such a crisis-riven world. These reflections resonate with her project’s underlying theme: that violence under religious auspices—whether in Ayodhya’s Babri mosque demolition or in the genocide in Palestine—is a recurring historical phenomenon. For Bhattacharya, these violent shifts signal changes in how societies define “modernity” and how certain narratives are legitimized while others are suppressed.

Bhattacharya recounted how, after graduating with a history degree, she was struck by the endorsement of violence against Muslims, Dalits, leftists, and liberals by the ostensibly secular Indian state. This prompted her Ph.D. inquiry into the origins of religious and nationalistic violence. She argued that the shift to religious revivalism in India—often placed in the mid-19th century—marked a pivot away from anti-colonial liberal reformism, laying the groundwork for a "modernity" that diverges sharply from early efforts at communal harmony.

Her talk shed light on how capitalist modernity erases or “homogenizes” the past. Bhattacharya contrasted pre-modern and modern ghosts: pre-modern ghosts were a part of reality, grounded in the natural world, while modern ghosts are abstract and universally “supernatural.” Pre-modern ghost stories revolved around the life and agency of spirits, with a realist approach to their presence, whereas modern ghost stories focus on death, with the ghost’s existence framed ambiguously. This transformation parallels how capitalism categorizes and commodifies beings, mirroring Linnaean taxonomy in homogenizing diverse identities and histories. Crucially, Bhattacharya argues that modern ghosts are uniquely uncanny, and indeed that the uncanny itself is a modern phenomenon. The indeterminacy that characterizes gothic ghost stories reflects a gap in the ability of modern scientific inquiry to make a clear category judgement—are ghosts real or unreal, alive or dead?—which means that the ghost can be familiar to the modern subject, but never fully understood, since they skirt clear classification. In contrast, premodern ghosts were incapable of being uncanny, since they were a part of a lived natural world that premodern subjects were always immersed in.

In a compelling analysis, Bhattacharya examined how “scientific spirituality” emerged to replace these older conceptions of the natural world. For instance, traditional beliefs once treated spirits as natural beings, requiring unique tools or rituals based on their type, much as one might need specific tools to hunt specific animals. In capitalist modernity, such spirits are dismissed and classified under the homogenizing term “ghost.” Bhattacharya links this transition to class formation, as societies redefined “superstition” to separate it from “religion,” ultimately reinforcing class divides. “Superstition” was relegated to women, children, and the lower classes, while the more rational “religion” was reserved for upper-class men.

Bhattacharya, however, warned against assuming a uniform experience of modernity across cultures, contending instead that modernity itself is singular but capitalism is not. She argues for a critical view of capitalism's variety, contending that global capitalism is often simplistically applied to all societies in a modernization framework, while overlooking local nuances. This view challenges the popular belief in multiple modernities, a stance adopted by some post-colonial scholars and even some proponents of Hindu nationalism, who advocate selectively integrating colonial elements, while rejecting others in favor of the “traditional.” Bhattacharya sees this selective borrowing as a dangerous maneuver, one that masks colonial power dynamics while reinforcing modernization ideals.

In the Q&A session, Bhattacharya expanded on this concept, explaining that capitalism can indeed assume diverse forms across societies. However, this variation often disguises the deeper reality that capitalism, in her view, inherently promotes a modernization paradigm. The audience grappled with this complex argument, seeking to understand the specific ways capitalism's “backways,” presented in Bhattacharya’s ghost stories, shape our experiences of modernity.

Through her work, Bhattacharya calls for a renewed critical examination of history, urging scholars to question who defines modernity, what is discarded, and what ghosts remain. Her lecture reminds us that past ideologies continue to haunt us, not as mere memories, but as living forces shaping our reality under capitalist modernity.