On November 18, 2025, Pollyanna Rhee (Landscape Architecture, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign) and John Levi Barnard (English, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign) engaged in a dialogue on “Environmental Humanities” as part of the Modern Critical Theory (MCT) lecture series.

Their dialogue responded to a culture that often treats environmental knowledge as abundant yet environmental action as elusive. Over the evening, the two speakers explored related yet distinct trajectories: Rhee examined the intellectual challenges the Anthropocene brings to historical study, while Barnard investigated how cultural ties and the economic forces behind them might limit freedom during the climate crisis.

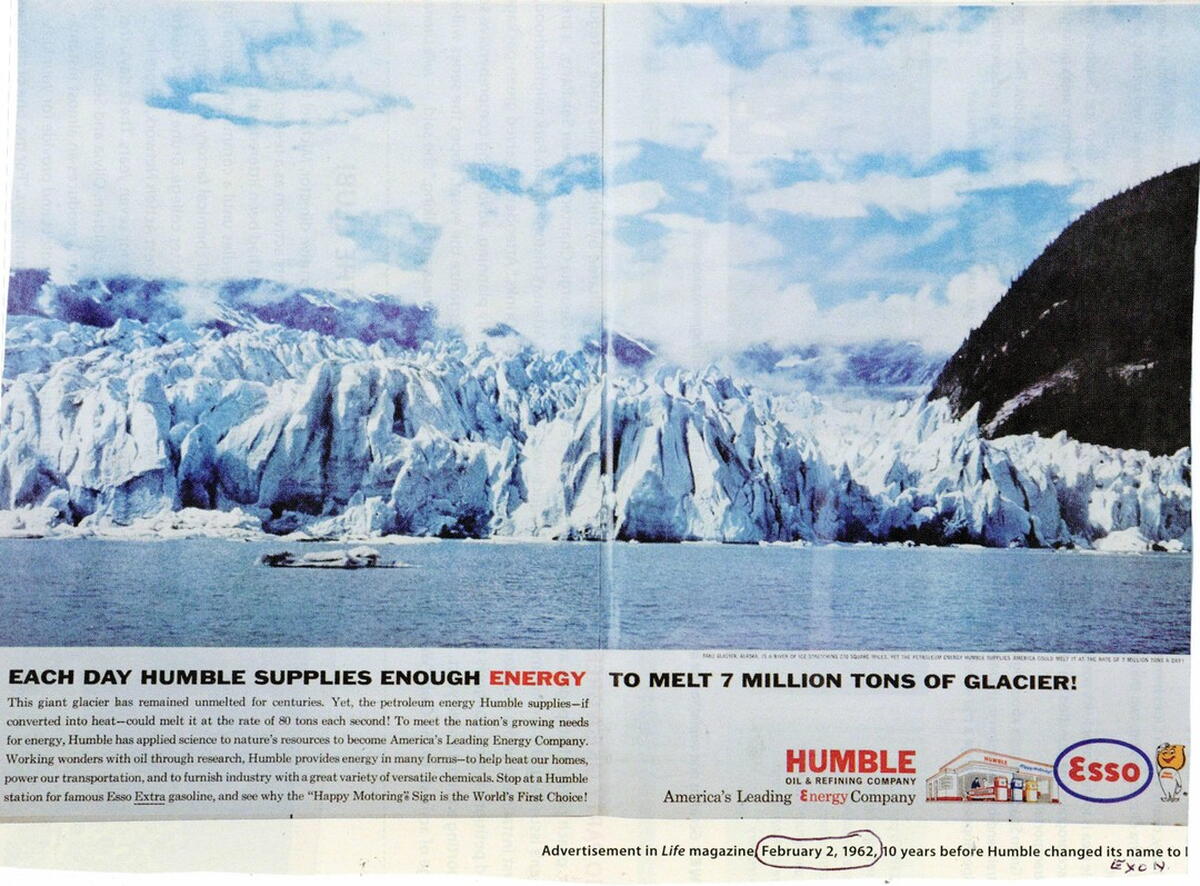

Rhee started by referencing a mid-century advertisement from the oil industry by Humble Oil and Refining Company that claimed that the corporation supplied enough energy each day to melt seven million tons of glacier. She highlighted this advertisement as a striking example of modern hubris, where fossil-fuel extraction could be celebrated as an emblem of national pride rather than of planetary harm. Rhee pointed out that historians, critics, and policymakers now live with the consequences of precisely such forms of industrial confidence. Yet what concerned her even more was the persistent assumption, often visible on university campuses, that technology alone could solve the climate crisis. She argued that this view represented a narrow fantasy that ignored the complex relationships between nature, culture, and power at the heart of environmental issues.

To illustrate this point, Rhee turned to the question of agency. She argued that scholars in the environmental humanities have long pushed back against linear, teleological narratives that suggest the present as the inevitable outcome of the past. Historians, she noted, are trained to navigate multiple and often contradictory sources, a skill that has become especially valuable now when the central intellectual challenge is understanding how human activity has become a planetary force. She highlighted the growing agreement among scientists and scholars that we are now in a new geological epoch called the Anthropocene. Humans, once seen only as biological beings, have also become geological agents.

Rhee drew on Dipesh Chakrabarty to elaborate this shift. In his foundational essay “The Climate of History: Four Theses” (2009), Chakrabarty argues that human activities such as extracting fossil fuels and industrial farming now happen on a global scale. These actions create both significant power and vulnerability. Humans can transform landscapes, alter atmospheric chemistry, and accelerate species extinction, yet they increasingly struggle to control the cascading consequences of those very actions. Rhee explained how recent extreme weather events clearly reveal the growing gap between what we can do with technology and our political commitment to address these issues.

This gap between human power and human responsibility, she argued, creates significant conceptual and ethical challenges for historians. Traditional historiography drew sharp lines between human agency and natural processes, following thinkers such as R. G. Collingwood, who claimed that, because nature lacks intention, it cannot have a history. Contemporary historians, however, face a world where nature and culture are intertwined. Landscapes once seen as untouched wilderness reveal rich histories of Indigenous cultivation, while modern infrastructures leave their own ecological marks. In this context, the idea of agency becomes hybrid, distributed across human and nonhuman actors alike.

To develop the idea of hybridity, Rhee introduced theoretical work such as Tim Mitchell’s “Can the Mosquito Speak?” (2002), which argues that what scholars call “nature” constantly shifts among social, technical, and material forms, undermining any strict separation between ideas and things. Rhee interpreted Mitchell as insisting that our thoughts depend on the false notion that human reason functions independently of material conditions, when in fact ideas are always intertwined with the infrastructures that support them.

From here, Rhee linked Mitchell’s insights to a broader critique of how historians have conceptualized agency. She cited Walter Johnson, who noted that historians often treat agency as something they can restore or confer on marginalized groups, especially enslaved people, without examining the liberal beliefs that originally defined full humanity as white, European, and male. Johnson questions whether “granting” agency is an act of historical justice, or simply a form of intellectual self-satisfaction. Rhee indicated that environmental historians face a similar challenge. When scholars attribute agency to nature, nonhumans, or ecological systems, what purpose does this agency actually serve, and whom?

In response, Rhee referred to scholars like Linda Nash who redefine agency as relational rather than individual. Drawing from Bruno Latour’s actor-network theory and Tim Ingold’s ecological anthropology, which see organisms and environments as mutually influential, Nash argues that intentions and actions arise not from independent subjects, but from networks of interaction among humans, landscapes, organisms, and infrastructures. In this framework, environments shape human choices as much as humans shape environments. For Rhee, such reciprocal thinking creates new opportunities for understanding historical causality while also compelling scholars to consider the ethical implications of their narratives.

Rhee concluded by revisiting the ongoing issue of environmental responsibility. She noted that public debates often swing between urging individual behavioral change and demanding systemic transformation. The former tends to foster a politics of personal virtue, while the latter addresses the deep-seated dependencies of fossil capitalism. Rhee questioned whether the humanities sometimes promote scholarship that reassures scholars of their moral correctness without leading to genuine political change.

Barnard shifted the conversation by proposing that climate change should not be understood as primarily an environmental issue. Instead, he suggested, environmental frameworks often treat ecological questions as secondary to what he called the “central” concerns of politics, economy, and culture. He argued that the category of “the environment” operates paradoxically: although it constitutes the material basis of all social life, it is routinely imagined as peripheral to it. Barnard argued that climate change is, in fact, a cultural, political, and economic issue that requires new approaches to humanistic inquiry.

Barnard returned to Chakrabarty’s claim that climate change represents a “moment of danger”—one that demands fundamental reconsideration of the Enlightenment ideals behind modernity. For Chakrabarty, the Anthropocene poses a stark question: has the modern era been an age of human freedom or an age of planetary domination whose consequences now threaten to restrict freedom for generations to come? If the latter is true, Barnard argued, the logic of the Anthropocene shows that our understanding of freedom might be linked to our reliance on fossil fuels. In this sense, the climate crisis is not just an environmental disaster but also a crisis of political imagination.

Barnard identified two types of “unfreedom.” The first comes from production systems. Drawing on Marx and Engels, he argued that the productive forces of capitalist society operate without democratic control. Decisions about which technologies to pursue and which landscapes to exploit are based on capital accumulation, not on public discussion. The rapid growth of artificial intelligence illustrates this idea. People are told that AI is necessary and unavoidable, even though its benefits are uncertain and its environmental costs are very high. For Barnard, the problem is not just too much technology but the expectation that the public must quietly accept capital’s choices.

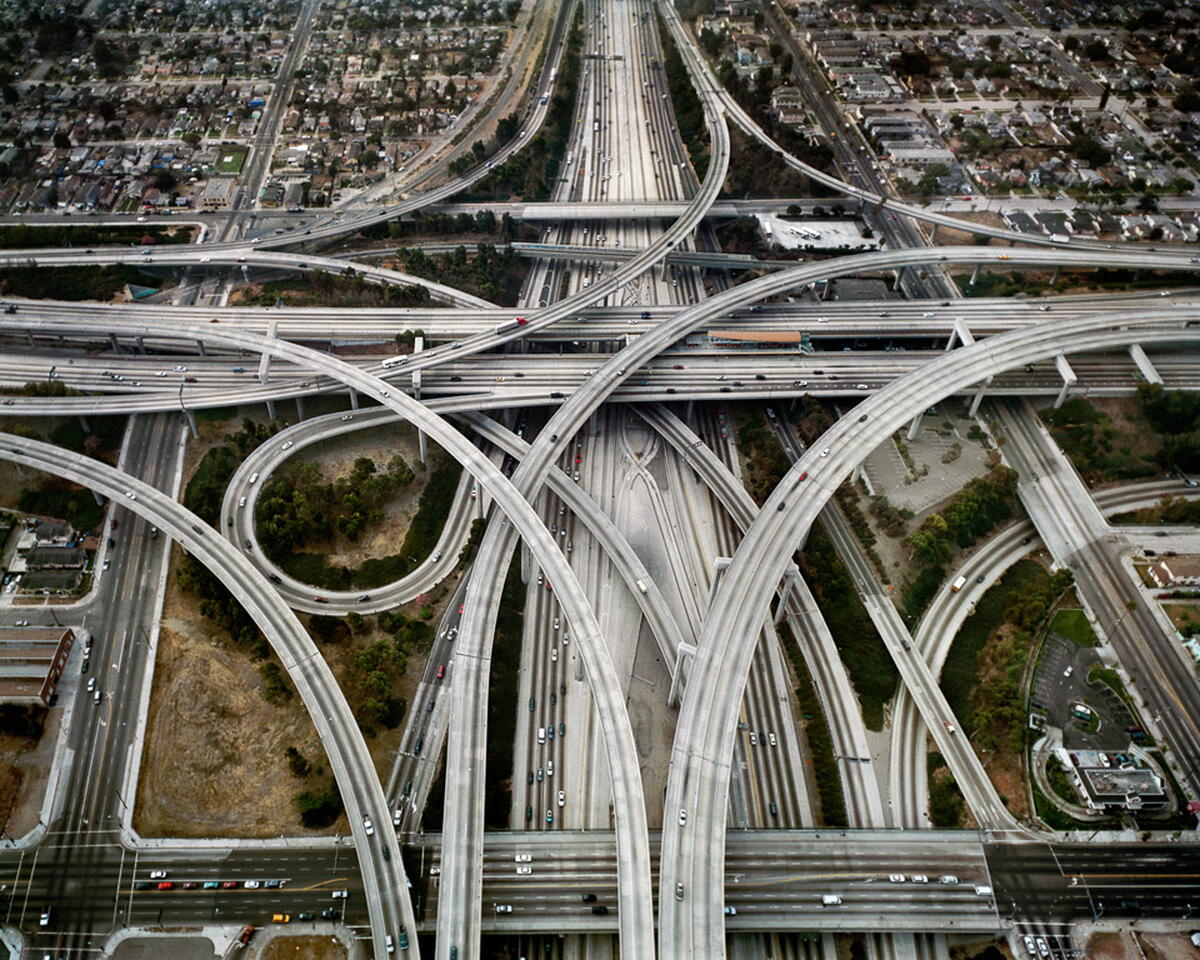

The second form of unfreedom, he pointed out, emerges through consumption. Twentieth-century infrastructures create desires and habits that make alternatives seem impossible. Los Angeles’s vast freeways serve as both real and symbolic spaces of entrapment, sustaining emotional attachments to cars despite traffic congestion and increasing emissions. Popular franchises like The Fast and the Furious (2001 onwards) reinforce the idea of the automobile as a symbol of personal freedom, masking dependence as liberation.

Barnard drew on Raymond Williams’s conception of culture as a “whole way of life” to explain why such attachments have lasted. He argued that fossil fuels are not just sources of energy; they are cultural experiences woven into identity, leisure, and aspirations. Citing Stephanie LeMenager’s work on “petroleum culture,” he noted how museums, advertising, and film aestheticize oil consumption and normalize its presence in everyday life. To illustrate the conflict between supposed freedom and real dependence, Barnard mentioned films like Deepwater Horizon (2016), where common activities like commuting and refuelling reveal how fossil fuels influence our daily lives. These portrayals demonstrate that consumer choices make sense only within the limits of the systems that govern them. He concluded that genuine freedom requires collective governance capable of redirecting production away from fossil fuels. The Anthropocene, Barnard argued, exposes the illusion that planetary exploitation can ever constitute true liberty.

In the joint Q&A session, Barnard and Rhee situated today’s technological growth, especially AI infrastructure and off-world visions, within a long history of extractive empire-building. Barnard likened new data centers to industrial chicken houses: hidden from view yet deeply destructive, enabled by figures like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos who accumulate land while offloading the environmental wreckage onto the public. Rhee built on this argument, highlighting that the dream of getting resources from other places is not new. It is rooted in the history of European colonialism and the American frontier myth. The desire to seek endless new territories, whether on Earth or in outer space, reflects longstanding anxieties about scarcity and a reluctance among those in power to imagine any alternative to expansionist extraction.

However, as D. Fairchild Ruggles noted from the audience, even the diverse approaches used by environmental humanities scholars seem inadequate for tackling the crisis. Barnard agreed, insisting that the impasse is not rooted in a lack of knowledge but in political and cultural constraints that limit what people believe is possible. He argued that the humanities are crucial because they encourage “crazy ideas,” like democratic control of production, that exist outside the current Overton window. Expanding cultural imaginaries, he suggested, is essential to imagining a future beyond extractive infrastructures. For Barnard, the route to true freedom begins not with new frontiers but with the collective desire to envision and demand something different.