“Dripping paint and newspaper clippings obscure a map of North America in State Names. The only names left visible are those that stem from indigenous sources. The collaged layers act as sequences of time, partially eclipsing the past while highlighting the injustices endured by Natives Americans throughout history.”

On September 27th, Dr. Rosalyn LaPier (History UIUC), an enrolled member of the Blackfeet Tribe of Montana and Métis, delivered a Modern Critical Theory lecture entitled “Land as Text: Environmental Studies.” While “Indigenous” and “Native” are globalized terms, due to the scope of this blog post they are invoked throughout to primarily refer to those people, communities, and tribal nations Indigenous to Turtle Island.

Through her education in dual Western and Indigenous knowledge systems, LaPier illustrated how the land, as a broadly encompassing term, has historically been a text for Indigenous people to transmit historical, sacred, and ecological knowledge. By articulating how a “majority of Indigenous “texts” are different, either through oral traditions or different ideas about how “texts” are written,” LaPier considers what it would mean for societies to reassess their idealized notions about documentation (and the “archives”) and instead to foster the continuation of reading other-than-written texts for knowledge transmission in the midst of a global climate crisis (as a result of the Plantationocene) where the changes in landscapes and ecologies threaten these Indigenous archives.

LaPier began by introducing herself and the two knowledge systems through which she has been educated. In addition to being an environmental and Native American historian, she has apprenticed with her maternal grandmother and eldest aunt in the traditional ecological knowledge and ethnobotany of the Blackfeet for over twenty years to become a traditionally trained ethnobotanist. She reiterated that while these two knowledge systems have their differences (perhaps ontologically and teleologically), “they are also reflective of each other” in ways that are conducive for learning and the transmission of knowledge. By referring to a map of the ecoregion of the North Great Plains, where the ecoregion (which is further divided by watersheds) and tribal Native nations and their territories “usually correspond,” LaPier showed the lands that she, her family, and community have been reading as texts. This particular ecoregion encompasses lands that are colonially referred to as Montana, North and South Dakota, Nebraska, Wyoming, Alberta, and Saskatchewan CA.

In August 2022, the All Nations Teepee Village was created in Yellowstone National Park to represent the enduring Indigenous connections to the land. The Roosevelt Arch reads “for the benefit and enjoyment of the people” with a teepee in its foreground - temporarily. This U.S. National Park turned 150 years old in March 2022.

Before continuing to the main portion of her lecture, LaPier encouraged the audience to consider a question that Terry Tempest Williams asks herself in The Hour of Land (2016) after Williams realizes that she had undoubtedly believed the terra nullius myth which rationalized the creation of Yellowstone National Park in 1872: “Who benefits from the telling of this particular story?” By contextualizing the influence of the doctrine of discovery and terra nullius in the dispossession of Indigenous land for the creation of the United States as a settler nation-state, LaPier revealed how (settler) coloniality has perpetually influenced Western and American understandings of land. From here, she recommended that we sincerely compare what Indigenous readings of the land can convey to us instead.

Indigenous land, or what she called “country” instead of “territory,” has been perceived differently by Western (settlers) than Indigenous peoples. By providing historical context of Indigenous countries by using Blackfeet Country as a point of departure, LaPier disrupted the Western notion of terra nullius in Indigenous lands and countries that were misperceived as “unoccupied” when, in actuality, tribal countries claimed them. Environmental historians, according to LaPier, have found that Indigenous countries often had “buffer zones” across their lands. She described buffer zones as being recognized by Indigenous communities as either “nobody’s country” or “everybody’s country” that provided a spatial distinction between Indigenous countries themselves or between humans and the supernatural. These later zones were often revered as sacred sites by Indigenous people, often amongst more than one tribal nation. The Treaty of Fort Laramie (1851), where the communal lands of “everybody’s country” was bestowed to the Blackfeet by the United States government, epitomizes the inability of a settler colonial mentality to conceptualize a relationship to land beyond (individual) ownership. Despite their lack of recognition in a settler colonial context, buffer zones are an inherent aspect of Indigenous landscapes and continue to be a feature of the land when read as text.

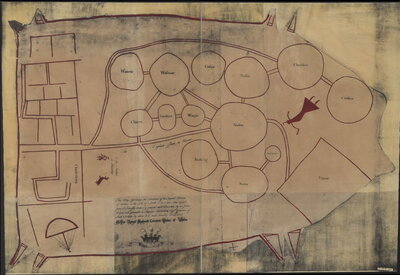

This map, commonly referred to as the Cawtaba Deerskin Map ca. 1721, depicts several the spatio-relationality of several tribal nations north-west of South Carolina. The Library of Congress explains that “The map, likely drawn by a Catawba or Cherokee chief, features thirteen circles representing Indian tribes in the colony. The tribes are connected by a network of doubles lines representing footpaths. Along the left side of the map is a depiction of the city of Charleston, with its rectangular street grid pattern and a ship in the harbor. Although the map may appear rather schematic to modern viewers, it accurately reflects the spatial relationships of the Indian groups and their interconnecting trails.”

An additional tenant of terra nullius is the assertion that land is “uncultivated” and/or “underutilized,” which LaPier further problematized when turning to the segment of Indigenous Land Use in her lecture. When conceptualizing Indigenous land and its usage, she reasserted the importance of not regarding it as “wilderness or empty or unused or unknown or unmanaged” since these descriptions are a facet of settler colonial rhetoric that rationalizes terra nullius and the dispossession of Indigenous lands. She importantly noted the similarities between Indigenous and Western land usage for permanent and seasonal villages and towns, boundaries between villages/towns/countries, and holy or sacred lands that invalidate the Western imposition of a terra nullius on Turtle Island.

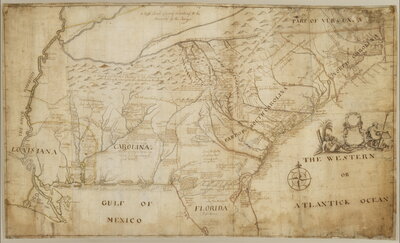

A map of the southeastern part of North America made by William Hammerton in 1721.

LaPier provided further context for what constitutes sacred land to Indigenous peoples. She explains that holy lands can either be created by the “divine” or by humans. Sacred land created by the divine are lands where humans cannot go since the divine lives there, lands where humans can temporarily visit (such as for prayer) since it is near to where the divine lives, or where humans can collect important plants, animals, or objects that were often subsequently used in ceremonies. The types of sacred lands created by humans have similar functions where shrines for prayer, for example, were acceptable to temporarily visit whereas a burial site is considered a sacred site where humans cannot go to. Lodges or spaces for healing, ritual, and ceremony are temporary sacred places created by humans for a specific use by/for humans. Again, these varying sacred places are constantly read in Indigenous landscapes as texts.

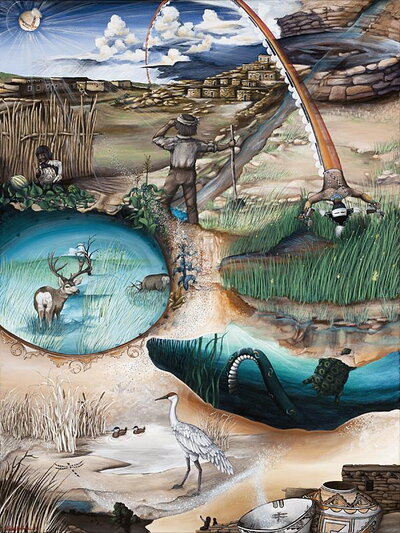

The painting was commissioned for the A:shiwi Map Art Collection to help the Zuni community connect to their places through artistic renderings of Zuni cultural landscapes.

LaPier read selections from her forthcoming article in Environmental History which included poignant personal descriptions of learning to read the land as a text through a process of intergenerational knowledge transmission. Annóóma, the Blackfeet word for “around here,” was always the precursor to the recital of stories of a place, after place, and another place whenever she was with her grandparents in Blackfeet country. This is what she described as a “landscape literacy,” where the land was understood to be a text and not just merely for resource use. Her grandparents were raised by their grandparents who had experienced a Blackfeet country before its reduction into the Blackfeet reservation, and so the ability to read the land beyond the confines of the reservation was taught to LaPier from a young age. This in part inspired her interest in exploring the Missouri River as a living archive of Blackfeet knowledge and witnessing the landscape of Blackfeet country; what has endured and what has changed. She reports a surprise when traveling outside of and very far from the Blackfeet reservation since “[she] knew these places because [she] heard the stories of them.” When industrial farming, ranching, and extractive industries have altered the landscape that interrupts an ability to read the history of the Northern Great Plains, LaPier maintains that stories can still exist even though the land has changed.

There were many thoughtful and engaging questions at the end of the lecture. In clarifying who authors the land as a text, LaPier explained that there are indeed multiple authors including various humans who have “written” historical moments into the landscape as well as have made continuous observations of ecological knowledge that is then embedded into the land to be read as knowledges for all communities or for some specific ones. Additionally, the divine are the authors of religious, spiritual, and sacred knowledges which can then be interpreted in the land by some particular individuals to then be shared amongst other people. LaPier made an important elucidation during this specific question that restated that the Western concept of “nature” is often understood to be a part of the supernatural in Indigenous ontologies and knowledges. In response to a question about the existence of places that may not have had any names, she explained that while there are places that did not have a name, this does not evidence that those places were unknown to Indigenous people and their countries. She explained that the concept of “in the middle” of those named places was also a kind of named/unnamed place. In the final question asked, LaPier explained that the stories of places and objects still exist even if they are changed or moved, such as is the case with damming and the misappropriation of signifiers of important or sacred places for Indigenous people by Western industrialization. While Indigenous communities must collectively address how sacred places should be approached when change has happened to them--for any variety of reasons--their communities’ knowledge keepers will continue to pass down accurate knowledge of their history, religion and spirituality, and ecology that derives from these places.