Written by John Claborn (English)

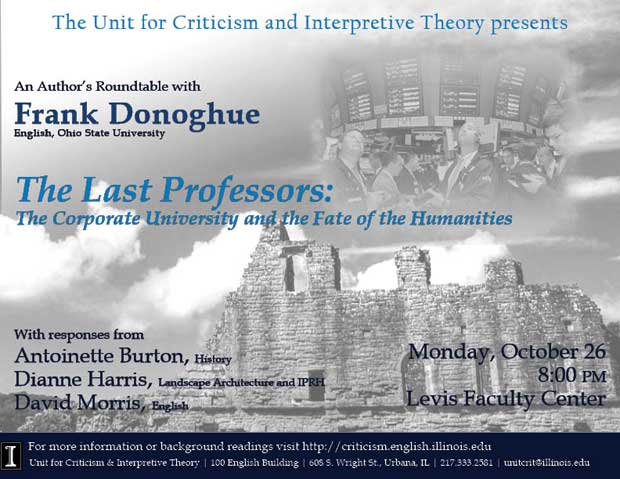

Monday night’s (Oct. 26) author’s roundtable and lively discussion with Frank Donoghue proved sometimes bleak and less often hopeful, but consistently provocative. Donoghue began his talk by recounting two formative moments that set a professor of eighteenth-century British literature on the path to writing The Last Professors: The Corporate University and the Fate of the Humanities. The first was his move from Stanford University, a financially secure institution insulated from state politics, to Ohio State University, where attacks on “professors who don’t really work” were rampant and budgetary constraints occupied faculty and administrators. This gave him a private/public double perspective on higher education, and it reminds us that he writes with an eye specifically to the problems of public schools like the University of Illinois. The second moment was his reading of such books as Dinesh D’Souza’s Illiberal Education and Roger Kimble’s Tenured Radicals in the midst of the then-emergent “culture wars” of the 1990s.

Joining an ever-expanding genre of books on the deplorable state of academic labor in higher education, Donoghue’s The Last Professors dismantles what may be our last comfort: the rhetoric of “crisis” used to characterize the plight of the humanities. “Crisis” suggests that current problems sprang up in the recent past and, therefore, they just may resolve themselves somehow in the near future. Instead, Donoghue reframes this crisis as “an ongoing set of problems” (1) in a “long dialectic between business and higher education” traceable back to the nineteenth century (23). Humanists, he shows, are still simply rehearsing the same debates put forth by Matthew Arnold and Andrew Carnegie in the Victorian era—debates about the usefulness of people who study and teach literature to corporate America’s bottom line. As history has shown, Carnegie’s utilitarian ideals of productivity and efficiency have proven more powerful than humanist ideals (though to be fair to Carnegie, he aspired to be a “man of letters”). By mapping a genealogy of corporate vs. humanities discourse within higher education, Donoghue challenges us to reformulate the debate’s key terms and move beyond the “rhetorical rut” of Arnoldian defenses of humanities education.

Donoghue then moved on to a critique of the “publish or perish” tenure system and academic freedom. He argued that the increased emphasis in recent decades on publication for determining tenure has lead to a “scholarly publishing industry” that places enormous pressure on upcoming generations of scholars. Productivity measured in terms of articles and books is symptomatic of corporate values, even though only about 2% of these “commodities” are ever cited. To conclude, Donoghue summarized arguments advanced in his new article, “Why Academic Freedom Doesn’t Matter,” in which he traces the history of how the principle of academic freedom became linked to the tenure system.

Each of the responses from Dave Morris, Antoinette Burton, and Dianne Harris, as well as the ensuing discussion, centered on current, concrete struggles within the university. Many good questions were raised: how can we find ways to critique corporate values without reverting back to empty arguments for the intrinsic good of critical thinking? What is the value of scholarly work when it rarely reaches a non-specialist audience and when it is viewed primarily as a means to obtaining tenure? What kinds of leadership exist, or should exist, to organize both full-time faculty and the exploited adjunct multitude into coalitions capable of combating regressive administrative policies? How do we make local coalitions formed around local problems more national (and international) in scope that can effectively address larger systemic problems affecting, say, Ohio State University, the University of California, and the University of Illinois?