In the sixth lecture of the Modern Critical Theory Lecture Series, Samantha Frost, Professor of Political Science at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, introduced us to the modern and contemporary theories of Biopolitics by focusing on three main theorists, Michel Foucault, Robert Esposito, and Giorgio Agamben, all of whom were ultimately concerned with Late Liberalism. These theorists shed light on the “theoretical hubris” of the Enlightenment, the massive failure of the promise of liberalism in the use of law to protect individual lives, dignity, and rights, because in Frost’s words, “the logic of liberalism unfolds catastrophically, and in doing so, it captures and identifies its other, so they become the target of its violence.” The premise of biopolitics is therefore to examine the entanglement of lives in larger societal systems: to address the ways in which “living bodies [are] mobilized in and for the political purposes” and to examine “how lives become the target of liberal politics and the means by which political strategies are carried out.”

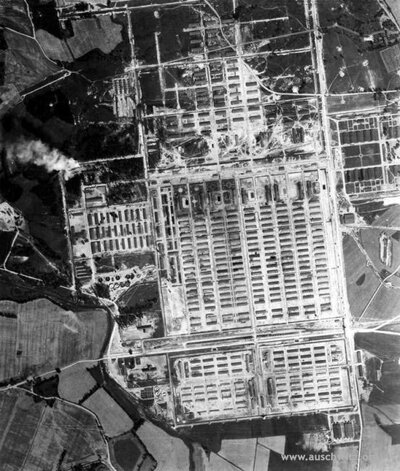

Frost started with the Foucauldian definition of the topic, that is, by showing how the mode of affecting people’s action is historically sequential, shifting from sovereign power to disciplinary power and ultimately to biopower. The first shift occurred in the eighteenth century with the disarticulation of wealth (economy) from the sovereign (political power) as power no longer resided with the church or absolute monarch. This shift in turn meant that the health of the nation became coincident with that of economy, meaning that the populace became a resource and an energy for the economy of the nation to foster. The second shift occurred in the early 20th century, when the identification of the nation with the living bodies of the populace led to strengthening of the use of biological and physiological language when talking about national identity. This, in turn, caused state racism and violence against certain groups. The mass genocide of the Holocaust is the tragic consequence of liberalism that evolved into the paroxysm on the Jewish population, using the very bodies of the German population. With the rise of Neoliberalism in the wake of WW2, the biopolitical management of bodies and population intensified, as the economy increasingly became identical to the nation, while the state became merely symbolic without a governing function. The management of economy by law was deemphasized, and instead law was regarded as an entity to install and maintain the mechanism which would lead to economic growth. Concurrently, the biopolitical turn morphed from state-led eugenics into efforts to incentivize individuals to develop the patterns and habits required to keep the economy going, meaning that self-management and self-curation became the norm, default, or standard for every human activity including biological health, financial health, etc.

Comparatively, Esposito’s account of Biopolitics is less about the state and more about bodies of people. He pays particular attention to the immunizing actions that erupt within the social community to expel that which is foreign to the body of the community. While Foucault was concerned more with the discourses of power and knowledge as the center of the management of life, Esposito argues that activity itself or the relation that it entails is what makes the community a community, while denouncing the communitarian notion of community. For him, there is nothing substantial about community prior to the formulation of relations because relation itself is the basic, enabling condition. Esposito introduces two main concepts: communitas and immunitas: the former is defined as the debt or gift at heart of community that opens the self to the other, whereas the latter is defined as a suspension of obligatory relations (exclusionary inclusion). So, communitas requires immunitasto prevent itself from collapsing. In Esposito’s analysis, the modern structure of power dynamics between communitas and immunitas is analogous to Thomas Hobbes’s account of the structure of power, that is, by the mechanism of the social contract by which individuals must give over the right to freedom to the community to acquire membership, while the sovereign power remains immune to this rule (the privilege of suspension). In other words, each member of the community must be in a civil condition while the sovereign stays in the state of nature because for everyone to have right to freedom, they must all be equally vulnerable to the sovereign as the source of governing power. The Holocaust is then an extreme example of negative biopolitics such that community kills itself or parts of itself in order to survive, failing the promise of liberalism. The important question, Frost asked, is whether “it is possible to foster the positive, protected dimensions of the immunizing dynamics without any negative, destructive dimensions.”

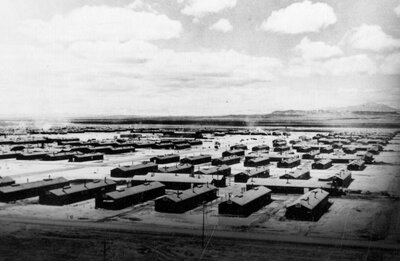

The privilege of suspension is what constitutes sovereign power for Agamben as well. By extending his research to pre-modern history, he examines how the biopolitical logic of liberalism allows the sovereign to be exempted from the law and inflict temporary arbitrary violence on people. Referring to Aristotle, Agamben discusses zoë (basic animal life) and bios(formed political life) to address the copula, the bridge that ambivalently joins and separates the two concepts, reinforcing the relationship of the two. Neither is exclusionary of the other, but rather bios includes zoë by its exclusionary inclusive mechanism. This logic of the copula is what Agamben calls the anthropological machine by which we humans have always historically (at least in the Western tradition) tried to maintain the relation and distance between zoë and bios. This distinction as well as the anthropological attitude within the bivalent yet ambivalent system is crucial when it comes to the moments where the sovereign must decide who lives and who doesn’t (for example, the right to live for those who are in vegetative state) because these are the moments when the sovereign exception collapse and create bare life which refers to a peculiar condition of persons, abandoned by law due to the act of suspension of law. He calls those who occupy this status as Homo Sacer. Importantly, the suspension of the law does not result in turning people in the condition of bios into that of zoë, but in that of the peculiar suspension. For example, Jews in the time of Holocaust were killed without their deaths being recognized in the law as murder; and Japanese Americans were forced into encampments as an exceptional administrative decision by the government, a suspension of their rights as citizens. This collapse occurs on a regular basis even in contemporary society as many people are rendered as bare life, as in the case of immigrants in detention centers or Black Americans who can be killed with impunity by the police.

Frost extended the discussion on Agamben’s ambiguous concept (or his new interpretation of Wittgenstein on this matter) of “form of life” and “form-of-life” which, she importantly noted, renders “positive biopolitics.” This topic indeed made the Q&A session lively and constructive in many ways. Agamben questions the Aristotelian bivalent premise of the copula (on zoë and bios) and rather sees that life is always already formed as opposed to the clear binary of the ancient understanding. In other words, “form of life” is already an ongoing, habitual use of the world you live in, which in turn transforms yourself while concurrently transforming the world. Knowing that “form of life” has political consequence on both yourself and the world can, in fact, lead to craft the “form-of-life” to live an ethical life. With this affirmative aspect of Biopolitics, quite distinctive from the preceding ones, Frost concluded the lecture on Biopolitics while hinting at the necessity for and her commitments to a more non-Western approach to further the understanding of the matters in question.