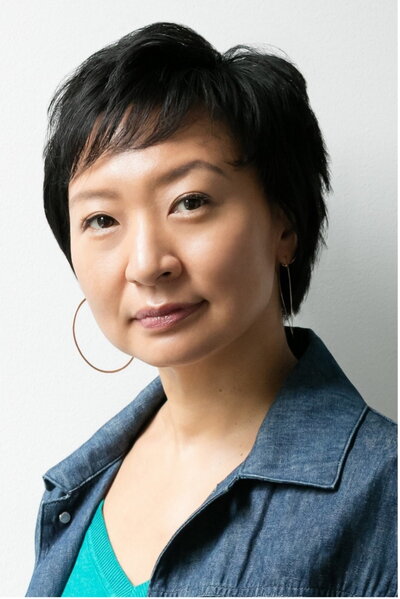

The third event of the year-long series, “In Plain Sight: Reckoning with Anti-Asian Racism,” co-organized by the Unit for Criticism and the Department of Asian American Studies, took place on Tuesday, March 22, 2022. Cathy Park Hong (Rutgers), author of Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning, winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award and Pulitzer Prize finalist, spoke to Susan Koshy (UIUC) and Soo Ah Kwon (UIUC).

Addressing both aesthetic and political challenges, Prof. Soo Ah Kwon began the conversation by asking Hong about how she addresses the paradoxes of anti-Asian racism in her life and work. She responded by turning to the origins of Minor Feelings, describing her frustrations with the binary power frames that characterize the language we in the United States often use to talk about race. Referring to the tendency to dichotomize race and racism in terms of black and white, victim and aggressor, Hong points out that no racial demographic fits such binaries.

For Asians, Hong explained, this creates a number of paradoxical identities, including the model minority. Borrowing Vijay Prasad’s formulation, she said the question asked of Black people—“how does it feel to be a problem?”—becomes for Asians, “how does it feel to be a solution?” The status of model minority functions as a “solution” to the problem of racism by discounting struggles that other minorities face while simultaneously positing that Asians do not struggle with racism like other people do. In labeling Asians as the model minority, other Americans elide Asian racialized experiences such as melancholia and anguish. Asian feelings are, therefore, not received or held in the United States, and, as Hong put it, “When our feelings aren’t held, it generates minor feelings,” creating a “detachment from the body and who you are.” The model minority myth also obscures more extreme forms of racism. During various crises, as has become apparent through the COVID-19 pandemic, Asians have become targets of more explicit racism. Many of the same stigmas of disease, contamination, sexual decadence that Asian immigrants were once associated with have reemerged with the virus. A hundred years later, Asians are still considered outsiders to the United States.

These paradoxes create a conflict between a sense of Asian internal life and the reductive, broad strokes that have been painted over Asian externality. While the narrative that has been imposed on Asian Americans is slowly changing, the only way to continue changing the narrative, Hong said, is to speak out as much as possible and to make Asian Americans visible in politics, arts, and activism.

Continuing the conversation about Hong’s responses to writing about race, Kwon asked about Hong’s ambivalence and self-doubt in writing about such a personal subject. Hong framed her response by pointing toward the differential power relations that define people’s positionalities within institutions or neighborhoods. In her case, she was raised with a taboo, enforced and policed by fellow Asian Americans, around speaking about Asian identity. Hong referred to Min Hyoung Song’s project The Children of 1965: On Writing, and Not Writing, as an Asian American, in which Song interviewed Asian American writers, all of whom bristled at being identified as “Asian American writers.” Hong characterized this resistance as a desire to avoid being pigeon-holed and as an expression of the limitations that identity politics can place on artists, recentering attention on their identity rather than their aesthetic abilities. While she could relate to her fellow writers’ resistance to being identified racially, Hong also found it necessary to, as she put it, “pry that open and get at the root of where that came from.” Hong was raised not to talk about race—as a second-generation Korean-American woman, her family did not acknowledge racism in their home, and she had no Asian role models in the media to look up to. As Asian immigrants, her parents prioritized providing food, shelter, and education over emotional safety, leaving a gap in which Hong developed a sense of isolation from her family, school, pop culture, and politics.

Through Prof. Susan Koshy’s next questions, the conversation shifted to how Hong rendered these feelings through her writing. “To understand what ‘Asian American’ is,” Hong said, “is to poke at it from many directions.” Turning to form, Hong quoted WH Auden’s statement that poetry “might be defined as the clear expression of mixed feelings.” As a poet, she found that poetry helped crystalize her mixed feelings and yet still allowed for irresolution, responding to questions with further questions rather than with answers. That, she stated, is what Minor Feelings is. Paraphrasing James Baldwin, Hong said she attempted to lay bare questions smothered by answers. She chose to transpose her poetic impulses into essay form because the elasticity of the essay genre can be described as a coalition of genres. By publishing Minor Feelings as an essay, she could better approach her questions from multiple directions such as memoir, history, and social science. The question of “what is ‘Asian American’?” was particularly informative to the form of Minor Feelings—where Hong said that whereas she would not have had the same ambivalence to writing about being Korean American, Asian American identity’s broad demographics, including populations as different as East and South Asians, leads Asian Americans to be apologetic about whom to exclude or include. However, pointing to Angela Davis’ argument that politics must drive identity, Hong pointed out that Asian Americans are bonded by a similar struggle. It is therefore helpful to think of “Asian American” as a verb rather than “as a thing attached to you.”

Continuing the thread of identity and politics, Koshy asked Hong about how rage and resentment, as emotions not often fully granted to Asian Americans, fit into her model of minor feelings. Was rage a minor feeling or a major feeling that moved one in a different direction politically? Hong responded that the difference between a minor and a major feeling is whether it is internalized or externalized. Rage is therefore a major feeling which, in some contexts can be healthy and expressed as a form of optimism that society, rather than yourself, can change. As she put it, “Rage can be harnessed into a movement, into action.” Resentment, on the other hand, is internalized, and, when left, “curdles into something that becomes self-destructive,” leading to unhealthy politics. A lot of Asian Americans, she says, feel like they don’t have a right to rage because their struggles aren’t as difficult as the struggles of Black and Latinx people. However, it is not a competition, and Asian Americans have every right to feel rage and do something about it.

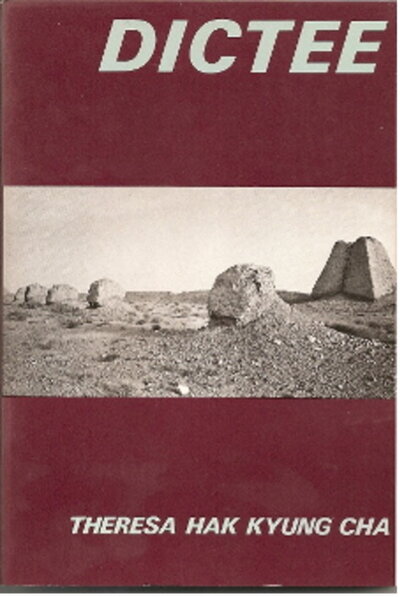

The conversation closed by returning to Hong’s multiple approaches to writing about Asian American identity in Minor Feelings. Kwon and Koshy asked about the chapters “Portrait of an Artist” and “Bad English” respectively. “Portrait of an Artist,” Hong responded, was vital to Minor Feelings because she wanted to engage with Asian American life, friendships, artists, and activists. As she wrote about Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s life, Hong was resistant to writing about her rape and murder. And yet, she found she could not look away because of her rage that Cha’s rape and murder was hardly known or acknowledged. In the erasure of the violence enacted on Cha, Hong saw similarities to forms of intergenerational trauma, particularly as associated with the Korean War, a war that is often called the Forgotten War. She sees the same trauma now being enacted on the Asian American women who have been assaulted since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Regarding “Bad English,” Hong stated that, as someone who had grown up thinking that poetry and short stories should be written in an elevated voice, she found weaponizing bad English in poetry to be liberating and formative. Referring to code switching as an act of survival, Hong described as a “traffic of different vernaculars,” the ways in which English is used differently in the contexts of the home, in music, and with friends. Hong asked why we don’t see these different voices in poetry and questioned what it would mean to write poems in the voices Asian Americans heard growing up. She posited that doing so would be a form of decolonization in literature and poetry, a way of telling an ethnic or an immigrant story.

The conversation then opened up to Q&A with the audience. Questions addressed the non-neutrality of language, changing perspectives across generations of Asian Americans, and the role of han in Korean American communities more specifically, anger and coalitional politics, and self-care and healing in the aftermath of confronting racism and microaggressions.

While the conversation that occurred on March 22 has been concluded, in the spirit of Hong’s poetic impulse, “In Plain Sight: Reckoning with Anti-Asian Racism” will continue to pursue further questions and discussions regarding historical and contemporary anti-Asian racism through an upcoming faculty-graduate seminar and a conference. “In Plain Sight” is funded by the Chancellor’s Call to Action to Address Systemic Racism and Social Injustice Research Program.