On Tuesday October 25, 2022, Professor Rubén Gaztambide-Fernández (Toronto) delivered “The Pedagogies of Solidarity,” a lecture about understanding and developing pedagogies of solidarity. Quoted content is from the lecture unless noted otherwise. All images are by 愚木混株 Cdd20 from Pixabay.

Rubén Gaztambide-Fernández’s “The Pedagogies of Solidarity” is an invitation to interrogate the assumptions about and varying meanings of solidarity. Seen in another light, his lecture was a thoughtful lesson in how we can derive a principle for a way of being with and relating to others from an experience of feeling distance between ourselves and others. Underlying this lecture was the methodology of continually returning to questioning what we know about solidarity. This methodological point is significant because Gaztambide-Fernández does not issue necessary and sufficient conditions for what counts as solidarity. Rather, he invites a dialogue about what it means for us to be in solidarity and insists that we shift from discussing the mere feeling (or disposition) of solidarity to understanding that political commitments and moral obligations create the foundation for robust, creative solidarity.

At the core of this inquiry was an interpretation of a photo—a beaming infant with his mother. Pictured was a young Rubén, sitting comfortably and happily in his mother’s crossed legs. Her finger appeared to be hooked on his checkered overalls, keeping him in place while “he reached forward with his toes extending to touch the world from the comfort of his mother’s lap.” Despite his mother’s eventual explanation that her hooked finger was really a tickling finger, Gaztambide-Fernández views the photo and sees himself being held in place. But a sudden unhooking came when, at eleven years old, Rubén asked his mother whether men could be feminists. His mother replied: “Men could not be feminists, but men could be allies of feminism. They could stand by women and support the struggles from the sidelines. Men could be solidarios with women.”

Gaztambide-Fernández’s hope—perhaps even expectation—was that his mother would answer in the affirmative, to communicate that her son was so close to her that he was also close to the struggle of women. Yet, where the young Rubén wanted an assurance of his mother’s love, he felt he was met with distance. It was difficult to ignore the gnawing feeling that this particular rupture between mother and son was inevitable. No matter how much we love our children, we cannot stave off the mutual disillusionment that occurs when the continuity of mother and child is broken by the personal, political, and social recognition of mother as woman and son as cisgender man.

In that humble and vulnerable position, Gaztambide-Fernández recalled that it was his mother who taught him that “tenemos que ser solidarios.” He said, “The adverbial form (solidarios) matters because solidarity is a way of being in the world that requires a modification of one’s own behavior. Solidarity involves action directed towards another, but which transforms the self. It is an orientation towards transformative action. […] Our ability to be in solidarity with others hinges on recognizing that others are beyond our capacity to know or understand.” In this lies Gaztambide-Fernández’s distinct contribution to the scholarly pursuits of solidarity. There are many competing expressions of solidarity, but Gaztambide-Fernández suggests that those understandings do not need to be policed and argues that “solidarity can be, in fact, a failure to grasp.”

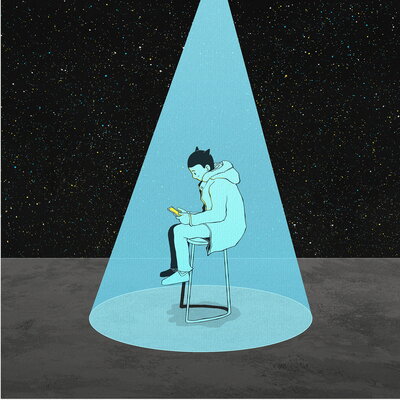

This new conception—this pedagogy—of solidarity may strike some as counterintuitive because we often assume that solidarity is always and only a unifying enterprise. When we consult the real world, however, we see a process of solidarity that has no such guaranteed outcome. Sometimes, in response to the call for solidarity, we try to grasp others and we fail. Does this failure mean that solidarity is off the table? Worse still, does it mean solidarity is impossible without a moment of grasping the other? According to Gaztambide-Fernández, “Solidarity cannot seek to fix the other in place but to create the conditions for subjects to be otherwise, for that which is ungraspable to flourish.” Even in the failure to grasp—perhaps especially in that “failure”—we see people. This moment of recognition inspires our capacity for creative solidarity.

For Gaztambide-Fernández, the question of whether men could be feminists ultimately gave rise to the more general question of whether we can be in solidarity with each other, a question that demands social and political attentiveness. It appears that the global community strives for solidarity when, for example, there are over 1.7 million social media posts tagged with “solidarity” (and that is not counting #solidaridad and #solidarité). But, as we know, things are not always what they appear to be. Gaztambide-Fernández pointed out that often “to be in solidarity today is to claim a higher moral ground without having to actually enact this morality or risk the loss of a loved condition or object.” Through a critical lens, we see that solidarity can be and often is detached from concrete political commitments and action altogether.

A pedagogy of creative solidarity offers us a way of resisting detached solidarity. Our capacity for solidarity rests in reciprocal recognition but the reciprocity in question comes with no promise of total understanding and closeness. Gaztambide-Fernández’s pedagogy of solidarity tells us that “solidarity is not a grasping but an ungrasping, not a knowing but a becoming.” A near antonym for “grasping” is “liberating.” From Gaztambide-Fernández’s notion of a pedagogy of solidarity—and in prioritizing the act of solidarity (over the disposition)—emerges the conditions for the possibility of liberation. I am liberated when I understand and allow for space between me and those I claim to be in solidarity with. The other is liberated from my expectation of and desire for total understanding. Acceptance of our inability to grasp or “pin the other in place” liberates us all from the threat of the loss of solidarity.