|

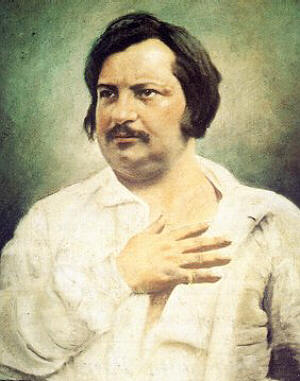

| Honoré de Balzac by Louis-Auguste Bisson, 1842. |

Written by Patrick Bray (French)

My current book project looks at how the novel, since the birth of the modern concept of literature around 1800, is incapable of incorporating a coherent theory, or a theory of itself, within the text. When a theory is included in a novel, it must obey aesthetic concerns – its relationship to the “outside” of the text is secondary. To take a famous example, Proust’s In Search of Lost Time contains hundreds of “theories” formulated for the most part by the narrator. But the narrator himself is a character who changes over the course of the novel from a boy to a depressed hypochondriac to a writer. How do we assess the validity of any of the novel’s theories when the fictional text itself is unstable?

For the five minutes or so I have today, I’d like to bring up a novel I’m reading at the moment, Balzac’s 1831 The Wild Ass’s Skin, or La peau de chagrin. This is Balzac’s first realist novel – it depicts the political disappointment of the failed revolution of July 1830 and a society that has been corrupted not only by money but by a disconnect between words and deeds. Obviously this is a situation very foreign to all of us. What has always struck me about the novel is that the title character, if you will, is a magic talisman from the Orient. How do you have a credible realist novel that depends so much on a magic skin granting the hero whatever he wishes in return for some of his life force? For the old man who gives the hero the talisman, it represents the mysterious but necessary link between power, knowledge, and desire (Foucault avant la lettre) – in other words it is a fiction that reveals to us how the world works.

In case this seems like too much of a stretch, too close of a reading, you only have to look at Balzac’s prologue where he says that writers have a “second sight” which he calls a sort of talisman that would let them see anything in the world as an inner vision. Close your eyes and travel the world with Balzac. Within the novel, every conceivable theory in every discipline is used to try to explain the magic ass’s skin, and each theory fails. My favorite scene is when three scientists in succession come up short and one of them destroys his lab trying to understand the physical properties of the talisman – I have a fantasy of seeing an MRI explode when a neuroscientist tries to measure the brainwaves of a subject reading Jane Austen.

The point of Balzac’s talisman is not whether it is real or not, what’s its origin might be, but rather what it does, what it allows us to see. By placing a thin slice of unreality within a realist description of Paris, Balzac shows us that the novel presents and then represents reality: it is both historically accurate and a product of the author and the reader’s desires. Scientists, historians, and other positivists who love to read “suspiciously” in order to track down the relationships between power and knowledge, should remember the other term in Balzac’s trilogy, “desire”. The talisman, like literature in general, acts as a concentric mirror, reflecting back at the reader a focused image of his or her own reading desire.

Balzac makes us aware of the complicity between scholarship and techniques of power. Balzac’s novel works because it resists theories, because it puts them to the test and reflects back at the reader her or his own reading desires. How does the push for more quantitative analysis of literary works by digital humanists, as well as the instrumentalization of foreign literature departments into language service departments, share the same managerial tools of control as globalization or neo-colonialism. Franco Moretti, in his influential book Graphs, Maps, and Trees calls literary studies “the most backwards discipline in the academy” and advocates “distant reading” as opposed to close reading (which seems to me like outsourcing reading to computers). I think that literature’s inability to incorporate theory has an effect on the literary scholar who must look outside the literary text in order to justify an argument.

|

| "Reading Girl" by Gustav Adolph Hennig (German, 1797-1869) |