"We All Get Sick and Die"

Written by Dr. Catherine Prendergast (UIUC, English)

“We all Get Sick and Die.” That used to be the subtitle of my courses in disability studies. It announced that disability studies demands a shift in our frame of reference with regard to bodies, away from a presumption of their invulnerability. I promised students that when they left the class, they would either identify as disabled (many already did coming in) or as only temporarily able-bodied. That used to be a tall order for college students in their late teens or early twenties, but it’s not anymore. Now, thanks to COVID, my students are thinking about illness and death all the time.

That change of perspective has altered my syllabus irrevocably. As many professors do, I had a no-fail opening assignment to deconstruct the prevailing common sense before we explored our topic in depth. I’d start students out by looking at what on the surface seems to be a progressive policy: the elimination of plastic straws. From an ecological standpoint, plastic straws are an unnecessary consumer perk, to be eliminated like any other form of extraneous packaging. However, plastic straws began as an accommodation device, and indeed are still an accommodation device for people with a wide range of motor and/or neurological impairments. Disability activists, facing proliferating bans on straws in their cities or at their favorite coffee houses, began to fight back, calling out the inherent ableism of banning straws. As we read their critiques, students who had thought themselves moral for campaigning for the elimination of plastics, suddenly had to reconsider what disability activists were calling ableist performative wokeness. We began to widen our view of who benefits from accommodation devices: How many of us wore glasses? Relied on elevators to move into the dorms? Surely, they could just carry that box of books up ten stories. Students did research on how much of the world’s plastic waste is straws ( under 1%) and began to question why disabled voices were kept out of the discussions— corporate and civic—that have led to blanket plastic straw bans.

And throughout the semester I would sip openly, nearly obnoxiously, through a plastic straw in solidarity with crip defiance.

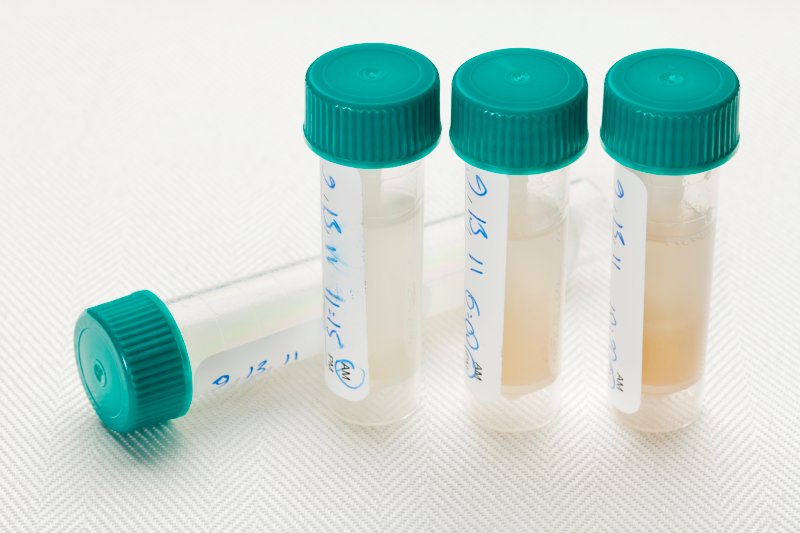

That lesson plan is now dead. COVID killed it. As the disabled activists themselves foretold, once the able-bodied saw themselves at risk of death or disability, nobody would be worrying about the environmental impact of plastic straws anymore. Now, plastic is everywhere: the take-out food, the hand sanitizer bottles, the plexiglass that would separate me from my students were I forced to teach face-to-face (which, thanks to my administration, I am not). All semester, my students must spit into a plastic tube twice weekly as part of our campus-wide COVID testing protocol. They must have two negatives every week in order to enter university buildings. After a semester of high percentage of inconclusive tests, on December 4, 2020, the test’s protocol has changed so that they will no longer spit directly into plastic tubes, but will spit through plastic straws into plastic tubes. Just like that, the dependence of everyone upon plastic straws for continued health and mobility has been exposed.

Although the pandemic would seem in this way to have been a levelling force, putting all students through a regime of medical testing and into greater touch with their vulnerability and mortality, in quieter ways it has been starkly stratifying. The University of Illinois, long lauded for opening Nugent Hall, an accessible dormitory for the physically disabled, and for staffing it with personal assistants through the Beckwith Residential Support Services program, had initially planned to keep Nugent Hall closed when it reopened campus. A petition by Nugent Hall residents and alumni forced the opening of the building, but the university maintained it could not, in the time of COVID, find assistants. But a disabled student resident I spoke with maintained that the real issue was that the university did not want to assume liability as the employer of these assistants. She easily found, and hired, her own. I join the Nugent Hall residents’ call for accountability over this deeply shameful chapter in our university’s history.

This chapter, too, the disability activists foretold. Alice Wong, a disabled writer and activist who depends upon a ventilator, wrote that times of scarcity and system stress provoke familiar conversations over “who is most likely to be saved.” From triage protocols in overwhelmed hospitals ranking patients by their chance of survival--and starting from the top of that list--to VIP access to cutting edge treatments, such as the antibody cocktail provided to Donald Trump when he got COVID, a pandemic is not so “pan” in its outcomes. COVID has exacerbated rather than erased already entrenched inequalities along the axes of race, class, and ability.

To this point I have been talking about the issues predominantly affecting the physically disabled. But my particular area of study is psychiatric disability. Because disability is the topic of my course, and students quickly learn that the stigmatization of disability is social (and therefore unnecessary) rather than natural, they are quicker to confide to me how they are really doing. And I would like to report they are not doing well. Anxiety and depression are running rampant, stemming from multiple causes: lack of social interaction; worrying about themselves, friends, parents or grandparents with COVID; and new financial concerns with un- and under-employment. I think of this surge of mental health concerns as the quiet epidemic within the noisier epidemic.

Universities were already ill-equipped to support the mental health needs of their students. The ratio of counseling staff member to students typically runs near 1600 to 1. It does not even take a specialization in psychiatric disability to see the inadequacy of that figure, considering the incidence of psychiatric impairments in the general population. But courses in disability studies help students see their struggles not as personal failings, but rather as the consequence of a collective ableist imagination of who the typical college student is and is not.

I taught my last class this week and said goodbye to my students from the Fall, telling them to keep in touch. Unlike many professors, I like teaching over Zoom. I don’t find it difficult to connect with my students. It helps to consider that every technology is also an accommodation device. I’ll say that again: Every technology is also an accommodation device.

Every. Single. One.