[On October 3, the Unit for Criticism & Interpretive Theory hosted the lecture “Derrida and Deconstruction” as part of the Fall 2017 Modern Critical Theory Lecture Series. The speaker was Geoffrey Bennington (Emory University). Below is a response to the lecture from Patrick Fadely, English]

“The Logic of the Trace”Written by Patrick Fadely (English)

One of the complaints sometimes lodged against deconstuction as a mode of critique is that it has little to say about the ‘real world’, that its focus on language and textuality makes it liable to overlook pressing social, political, and ethical problems. Professor Geoffrey Bennington’s talk showed the opposite to be true, and demonstrated how Jacques Derrida’s descriptions of the structure of language carry over into other domains, providing valuable insights into such exigent issues as political sovereignty and the ethical relation to other. Through his exceptionally lucid explication of deconstruction’s interest in language qua writing, Professor Bennington provided a sound introduction for those unfamiliar with Derrida, and at the same time presented a compelling argument that Derrida’s wide-ranging corpus can be thought of as a series of meditations on the logic of the trace.

One of the complaints sometimes lodged against deconstuction as a mode of critique is that it has little to say about the ‘real world’, that its focus on language and textuality makes it liable to overlook pressing social, political, and ethical problems. Professor Geoffrey Bennington’s talk showed the opposite to be true, and demonstrated how Jacques Derrida’s descriptions of the structure of language carry over into other domains, providing valuable insights into such exigent issues as political sovereignty and the ethical relation to other. Through his exceptionally lucid explication of deconstruction’s interest in language qua writing, Professor Bennington provided a sound introduction for those unfamiliar with Derrida, and at the same time presented a compelling argument that Derrida’s wide-ranging corpus can be thought of as a series of meditations on the logic of the trace.

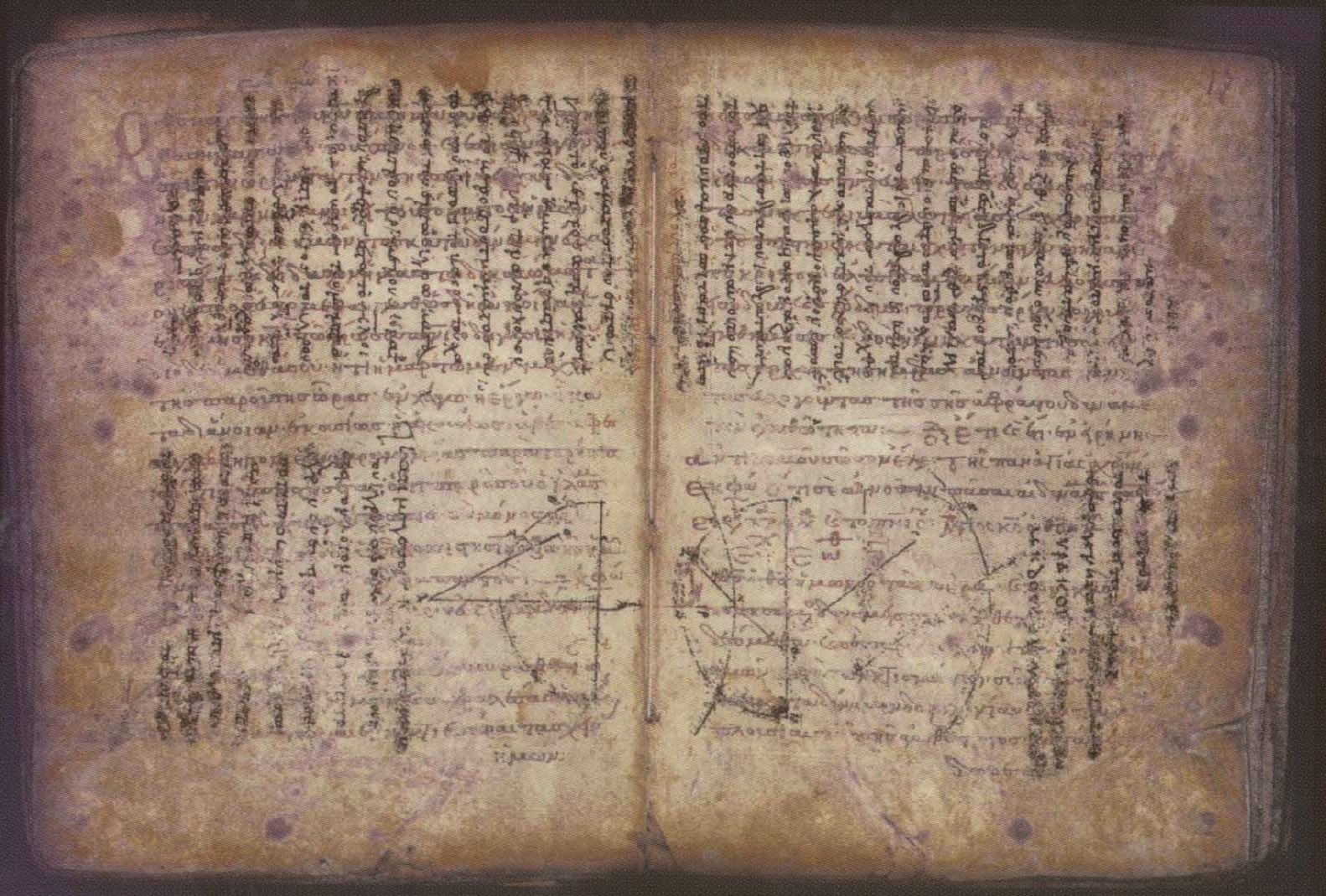

In order to understand the significance of Derrida’s thought, Bennington pointed out, it is helpful to start with Ferdinand de Saussure, whose reflections on language gave rise to the “linguistic turn” in twentieth-century philosophy. Saussure’s name is often associated with the dictum that the relationship between a word (the signifier) and its meaning (the signified) is wholly arbitrary—that there is no inherent reason to call a leafy, fruit-bearing plant a “tree,” rather than “árbol” or “Baum” or, for that matter, “table.” But this had been established well before Saussure, and was really only a starting point for his thinking about language. From this observation follows a question about the identity of the sign: given that the sign does not get its identity by virtue of its relationship to the thing it signifies (because that relationship is wholly arbitrary), where can we say this identity comes from? It cannot be the result of some primal scene of agreement on shared conventions, because language is always already inherited and handed down. The radical implications of this question—which Saussure eventually backed away from, but which Derrida took as fundamental—is that the identity of the sign arises only by a relation of difference between itself and all other signs.

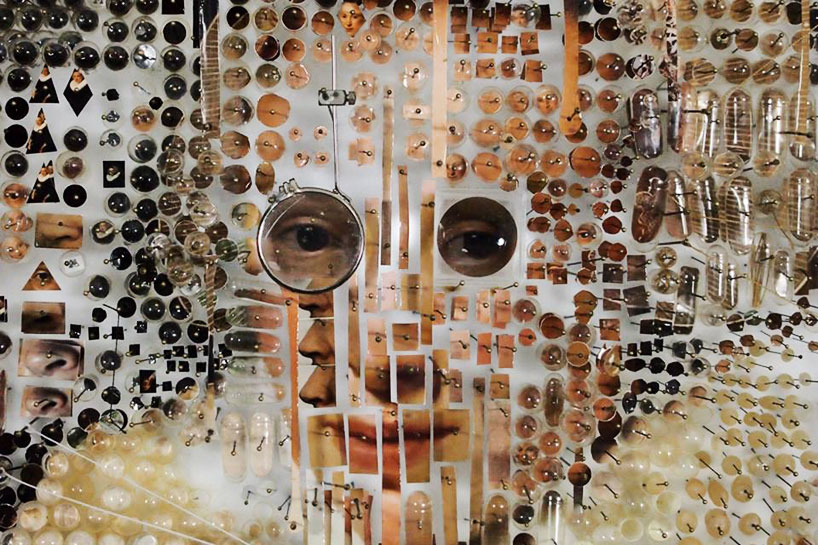

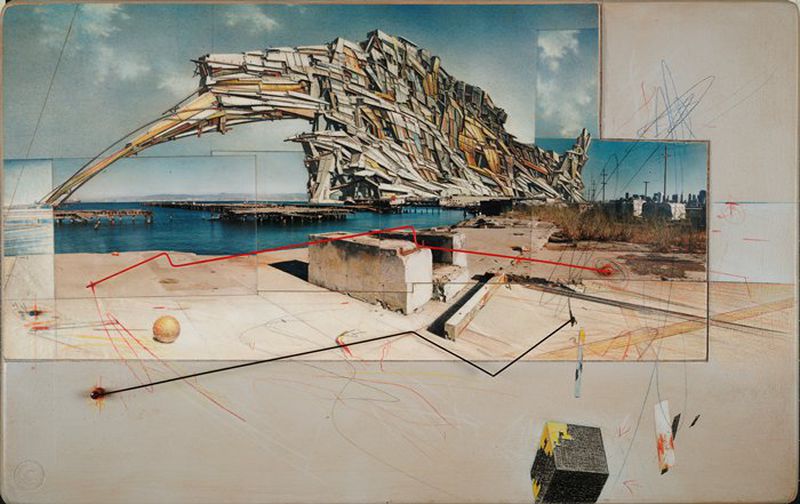

Deconstruction, Bennington explained, radicalizes this insight: once we have accepted that all meaning is the result of differential relations among signifiers, we are led to the conclusion that difference and absence must play as much of a role in our thinking about language as do identity and presence. This Derridean radicalization of Saussure’s insight inaugurates the logic of the trace, which served as the central concept in Bennington’s talk. In the logic of the trace, the presence of meaning is brought into being and accounted for by the play of a spectral and dynamic force field of differences—that is, traces. If we apply the logic of the trace to the field of language in general, then the structure of language comes to seem more in line with what has traditionally been said of writing (it bears witness to an absence, lacks vital motivating intention, and is subject to mechanical repetition) than what has traditionally been said about speech (it bears witness to a presence, is alive with the speaker’s intention, and exists uniquely in the moment of its utterance). If applied to politics, this same logic reveals that what we think of as sovereignty depends upon a prior set of internal and external relations that tends to dissolve the self-identity of sovereign power. When applied to the subject, the logic of the trace means that the self only emerges through a prior (ethical) relation among Others—that what we call the self is in fact always already an other. In all these areas, Bennington’s talk showed, these markers of identity—the sign, the nation-state, the subjective self—are compromised, spectralized, hollowed-out and in principle ‘defeated’ by the ‘others’ that bestow and disrupt their identification.

The Q&A raised several interesting issues. For example: is it not the case that we human beings are the agents that make meaning? Do we not stand outside the textuality of the real and establish is significance? Professor Bennington demurred, saying that although it is always tempting to try to find some meaning or agency that transcends the play of signification, it will always be pulled back into that orbit, if only because its entire raison d’etre is to put an end to the endless dynamism of difference. Professor Vicki Mahaffey asked about the relationship between deconstruction and psychoanalysis: couldn’t it be said that much of what Derrida posits about the logic of the trace bears a more than passing resemblance to what Freud (and, later, Lacan) describe in the relationship between conscious and subconscious, in which identity is based upon a prior relation to difference, and wherein intent and meaning are always haunted by unintended significance? Here Bennington pointed to Derrida’s reading of Rousseau in Of Grammatology, where Derrida insists repeatedly that he is not doing a psychoanalytic reading—a gesture of refusal that will be familiar to readers of Freud and Lacan, and one that hints at a deep connection between the work of deconstruction and the work of psychoanalysis.

The Q&A raised several interesting issues. For example: is it not the case that we human beings are the agents that make meaning? Do we not stand outside the textuality of the real and establish is significance? Professor Bennington demurred, saying that although it is always tempting to try to find some meaning or agency that transcends the play of signification, it will always be pulled back into that orbit, if only because its entire raison d’etre is to put an end to the endless dynamism of difference. Professor Vicki Mahaffey asked about the relationship between deconstruction and psychoanalysis: couldn’t it be said that much of what Derrida posits about the logic of the trace bears a more than passing resemblance to what Freud (and, later, Lacan) describe in the relationship between conscious and subconscious, in which identity is based upon a prior relation to difference, and wherein intent and meaning are always haunted by unintended significance? Here Bennington pointed to Derrida’s reading of Rousseau in Of Grammatology, where Derrida insists repeatedly that he is not doing a psychoanalytic reading—a gesture of refusal that will be familiar to readers of Freud and Lacan, and one that hints at a deep connection between the work of deconstruction and the work of psychoanalysis.

Toward the end of his prepared remarks, Professor Bennington had playfully staked out a ‘categorical imperative’ for deconstruction: “Be hospitable to the event of the arrival of the other in general; and be inventive when you can.” His talk met both demands admirably.