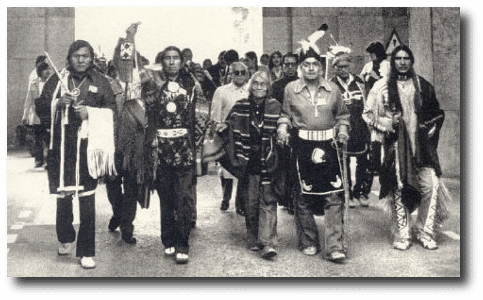

[On October 30, the Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory hosted a lecture by Nicholas Estes ( University of New Mexico) entitled ""Indigenous Studies: As Radical as Reality Itself" as part of the Fall 2018 Modern and Critical Theory Lecture Series. Below is a response to the lecture from Helen Makhdoumian (English). ] "Indigenous Studies: As Radical as Reality Itself": Nicholas Estes (Kul Wicasa) on Indigenous Studies." "Witnessing Indigenous Studies as Ever Radical, Global, and Inter/national: On Professor Nick Estes's Talk for the Unit" Written by Helen Makhdoumian (English) On October 30th, 2018, Nick Estes (Kul Wicasa), an Assistant Professor of American Studies at the University of New Mexico, delivered a lecture on Indigenous Studies for the Modern Critical Theory Lecture Series. Estes’s talk, titled “Indigenous Studies: As Radical as Reality Itself,” advanced a reading of “US history as a branch of the tree of Indigenous history and not the other way around.” In so doing, Estes conceptualized Indigenous Studies as developing and thriving in the face of imposed colonial definitions of nationhood, borders, systems of governance and relationalities, and of racialized discourses that serve the US nation-state’s interests. This attention to the locations of Indigenous Studies manifested throughout the evening, including in Professor Susan Koshy’s introduction of Professor Estes. Koshy began with a land acknowledgement statement that situated the University of Illinois’s founding as a land grant institution in the territorial dispossession of Native peoples. Citing the works of Joanne Barker (Lenape) , Jodi Byrd (Chickasaw) , and Jodi Melamed, Professor Koshy invited the audience to reflect upon our relationship to the land upon which this and other universities have been built. Reminding audience members that although there were no longer Indigenous nations within the state of Illinois, as Byrd and Melamed have emphasized, “the Native peoples who lived on this land for thousands of years before us are still our hosts." In his talk, Estes modeled how to keep the local and the global in mind when narrating the history of Indigenous Studies. Estes underscored the important role social movements have had on the development of this interdisciplinary field of inquiry. Indigenous Studies emerged alongside and through the spaces of the Red Power movement during the 1960s and 1970s. Such social movements informed Indigenous scholarship in the academy. Furthermore, Estes argued, that the colonizers were disqualified from narrating Indigenous peoples’ practices of making and maintaining relations with land and other life forms, human or otherwise. Indigenous Studies foregrounded Indigenous perspectives and interpretations as a decolonial method, and in this way it continues to decenter colonial knowledge and counter racist histories. Lastly, Estes underscored that Settler Colonial Studies, a field that overlaps with but that can differ in focus from Indigenous Studies, offers a limited model for thinking comparatively or globally. In its attention to death and destruction, such as Patrick Wolfe’s oft-cited “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Settler Colonial Studies has tended not to bear witness to Indigenous life, social reproduction, and futurity. Indigenous Studies counters this potential pitfall of Settler Colonial Studies by making clear that, to adapt Estes’s words here, the emancipation of the Native is indeed work being done by the Native herself. From this discussion of the relationship between Indigenous and Settler Colonial Studies and the local histories of connected liberation movements, Estes turned to Steven Salaita’s theoretical framework of “inter/nationalism” to interpret Indigenous solidarities on a global scale. As Salaita argues, “‘Inter/nationalism’ describes a certain type of decolonial thought and practice—not a new type of decolonialism, but one renewed vigorously in different strata of American Indian and Palestinian communities. At its most basic, inter/nationalism demands commitment to mutual liberation based on the proposition that colonial power must be rendered diffuse across multiple hemispheres through reciprocal struggle” (ix). Bringing Salaita’s work into conversation with Indigenous thought systems regarding the Big Dipper, Estes posited “constellations of co-existence” and “constellations of Indigenous solidarity” as a means to understand the relationship between liberation movements and Indigenous notions of co-existence. Estes envisions Indigenous Studies as an ever global and interconnected project and its work as having important lived repercussions. This notion of constellations and its implications of possibility and futurity held particular resonance with the campus audience. Estes indicated that the U of I’s “unhiring” of Professor Salaita ) all but gutted the American Indian Studies (AIS) program which faculty had previously built into a center for global Indigenous Studies. To build upon this inter/national way of conceptualizing Indigenous Studies and to elucidate these constellations already at play, Estes turned to a few case studies. His first example was the 1973 occupation of Wounded Knee by American Indian Movement activists, many of whom referred to Palestinians as relatives and identified Palestinian and American Indian peoples as simultaneously resisting occupation. [caption id="" align="align-left" width="483"] Indigenous delegates, including IITC's founders, enter the Palais de Nations, United Nations in Geneva for the 1st UN Conference on Discrimination Against Indigenous Peoples in the Americans in 1977. [/caption] Estes also highlighted the work of the International Indian Treaty Council (IITC), “an organization of Indigenous Peoples from North, Central, South America, the Caribbean and the Pacific working for the Sovereignty and Self Determination of Indigenous Peoples and the recognition and protection of Indigenous Rights, Treaties, Traditional Cultures and Sacred Lands.” Founded in 1974 at the Standing Rock Reservation, the IITC played a key role in peacefully ending the Iran Hostage crisis from 1979-1981. Estes showed how over the course of more than thirty years, persistent efforts by Indigenous communities and their allies at and beyond international meetings and conventions made possible the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) , a legally non-binding declaration that the General Assembly adopted in 2007. For his final case study, Estes referenced the 2016 #NoDAPL movement at and beyond the Standing Rock Reservation which represents, “growing anticolonial flashpoints of struggle and resistance” that “connected disparate communities of the dispossessed.” The protest camps at Standing Rock engendered a way to not just envision but embody a “radically different way to relate to others and the nonhuman world” and to witness the assertion of “Indigenous freedom.” These spaces, he continued, “welcomed the excluded and centered Indigenous lifeways.” Although Eurocentric processes of writing history would situate a social movement like #NoDAPL on a timeline, narrating a beginning and end to these resistance efforts, Estes’s lecture ultimately asked the audience to see the ongoing global, inter/national, and multiply-connected work of these Indigenous revolutionaries. [caption id="attachment_2083" align="alignnone" width="715"]

Indigenous delegates, including IITC's founders, enter the Palais de Nations, United Nations in Geneva for the 1st UN Conference on Discrimination Against Indigenous Peoples in the Americans in 1977. [/caption] Estes also highlighted the work of the International Indian Treaty Council (IITC), “an organization of Indigenous Peoples from North, Central, South America, the Caribbean and the Pacific working for the Sovereignty and Self Determination of Indigenous Peoples and the recognition and protection of Indigenous Rights, Treaties, Traditional Cultures and Sacred Lands.” Founded in 1974 at the Standing Rock Reservation, the IITC played a key role in peacefully ending the Iran Hostage crisis from 1979-1981. Estes showed how over the course of more than thirty years, persistent efforts by Indigenous communities and their allies at and beyond international meetings and conventions made possible the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) , a legally non-binding declaration that the General Assembly adopted in 2007. For his final case study, Estes referenced the 2016 #NoDAPL movement at and beyond the Standing Rock Reservation which represents, “growing anticolonial flashpoints of struggle and resistance” that “connected disparate communities of the dispossessed.” The protest camps at Standing Rock engendered a way to not just envision but embody a “radically different way to relate to others and the nonhuman world” and to witness the assertion of “Indigenous freedom.” These spaces, he continued, “welcomed the excluded and centered Indigenous lifeways.” Although Eurocentric processes of writing history would situate a social movement like #NoDAPL on a timeline, narrating a beginning and end to these resistance efforts, Estes’s lecture ultimately asked the audience to see the ongoing global, inter/national, and multiply-connected work of these Indigenous revolutionaries. [caption id="attachment_2083" align="alignnone" width="715"] "This is the Preamble to the Red Nation's Principles of Unity ratified by the first General Assembly of Freedom Councils in Albuquerque on August 10, 2018 - Pueblo Revolt Day. In the spirit of Popay!" From the website of the Red Nation (co-founded by Estes)[/caption] It was precisely this message that Estes carried into the question and answer session, where he responded to inquiries about possible future work in Indigenous Studies, his own methodologies in finding and pursuing these histories, avenues to study African American and American Indian histories together, and strategies used at #NoDAPL protest sites for teaching one another and cultivating kinships. Conversations continue, Estes reminded the audience, even if such events are not so present in the news. Furthermore, there are ripple effects and radical transformations that stem from such social movements, even if the media does not document these legacies. Like the movements he described, Estes’s lecture will undoubtedly have ripple effects on this campus.

"This is the Preamble to the Red Nation's Principles of Unity ratified by the first General Assembly of Freedom Councils in Albuquerque on August 10, 2018 - Pueblo Revolt Day. In the spirit of Popay!" From the website of the Red Nation (co-founded by Estes)[/caption] It was precisely this message that Estes carried into the question and answer session, where he responded to inquiries about possible future work in Indigenous Studies, his own methodologies in finding and pursuing these histories, avenues to study African American and American Indian histories together, and strategies used at #NoDAPL protest sites for teaching one another and cultivating kinships. Conversations continue, Estes reminded the audience, even if such events are not so present in the news. Furthermore, there are ripple effects and radical transformations that stem from such social movements, even if the media does not document these legacies. Like the movements he described, Estes’s lecture will undoubtedly have ripple effects on this campus.