[On April 27, 2019, the College of Fine and Applied Arts hosted a keynote address by Georgina Born (Oxford) entitled "Interdisciplinarity: Modes, Logics, Geneaologies, and Reflections," as part of the 2019 Festival of the Arts, Design, and Planning Symposium. Below is a response by Ian Nutting (Musicology).] Theorizing Interdisciplinarity: Georgina Born's Relational Ontology of Interdisciplinary Autonomy Written by Ian Nutting (Musicology) April 26-27 marked the end of the College of Fine and Applied Arts 2019 Festival of Arts, Design, and Planning. The final symposium, Methodologies, highlighted the breadth and diversity of the research methods employed by the faculty in the College, and featured both UIUC faculty and guest speakers.  The second of three keynote speakers, Professor Georgina Born (Oxford, Music and Anthropology), gave a talk entitled “Interdisciplinarity: Modes, Logics, Genealogies, and Reflections.” The following is a summary of and response to that talk. Institutional and Historical Conditions Following a general orientation to her ethnographic work on cultural production, which straddles the fields of music, anthropology, digital media studies, sociology, and sound studies, Born focused us on her current work: academic and nonacademic electronic and computer art music in the UK, Europe, and Montreal. As with much of her other ethnographic work, this is a kind of dialectics of institutional and socio-musical change. To frame her work, she laid out the institutional and historical conditions that have led to the rise of interdisciplinary art-science in the UK. Born finds the seeds of interdisciplinary artistic research in the neoliberalization of the university. The emergence of the knowledge economy coupled with policies of measuring and evaluating the “impact” of research led to a crisis of value: what’s the use of art? Born draws attention to the UK’s Arts & Humanities Research Council’s Cultural Value Project as an example. This runs parallel with the assumed epochal shift to what has been called “Mode 2” knowledge production (see Gibbons et al.): scientifically autonomous and intra-disciplinary research has been replaced by context-based and accountable inter- and trans-disciplinary research. Born criticizes this theory for conceiving of this shift in “science” and “society” as unitary and homogenous: the particular genealogies of different disciplines, including the imbedded practices and motivations, are erased and unaccounted for. In one sense, Mode 2 could be viewed as exemplified in artistic research, and yet by working through Henk Borgdorff’s analysis of artistic research and Mode 2 knowledge production, Born is left with his conclusion that the central experiential component, that is, the aesthetic experience, ultimately seems to escape not only conceptual and discursive articulation, but also the epistemic frame. The point is that these difficulties make clear the need to empirically discern and analyze the phenomenon of interdisciplinary research in its particular formations, which is exactly what she did with a team of ethnographers starting in 2004. Modes and Logics Based on some of her work for that project on art-science interdisciplinarity, which is generally created at the intersection of the arts, natural science, and technology, Born outlined, and then located art-science in relation to, three modes and three logics of interdisciplinarity. These modes are 1) integrative-synthesis, an additive mode that produces something like “multi-disciplinarity,” 2) subordination-service, a hierarchical mode that produces a master-servant relationship between disciplines, and 3) agonistic-antagonistic, a mode that seeks a break with the individual disciplines by transcending a mere sum or combination of them. Examples of this final mode include cybernetics, science and technology studies, and the medical humanities, as well as art-science. The logics are 1) the logic of accountability, which is concerned with public understanding and engagement, 2) the logic of innovation, which is concerned with things like economic growth and the creative economy, and 3) the logic of ontology, which is concerned with not just an epistemological shift, but an ontological shift in the very conception of the subject and object in research to something always already social and relational. That is, the object being studied shifts to something that emerges through particular practices and yet is something that “grow[s] more richly real as [it] become[s] entangled in webs of cultural significance, material practices, and theoretical derivations” (Datson, 13). This third logic is tied closely to the third mode, but all three logics are entangled in interdisciplinary attempts.

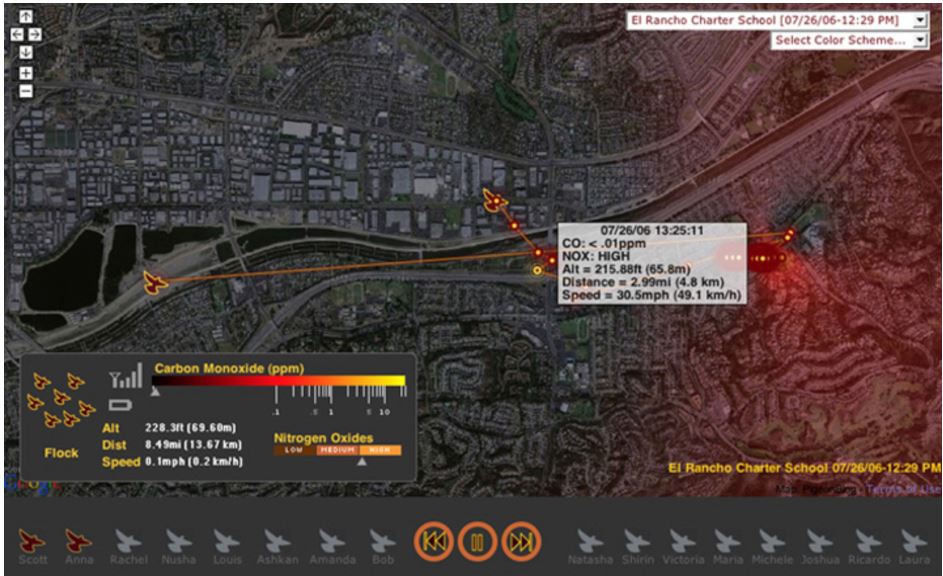

The second of three keynote speakers, Professor Georgina Born (Oxford, Music and Anthropology), gave a talk entitled “Interdisciplinarity: Modes, Logics, Genealogies, and Reflections.” The following is a summary of and response to that talk. Institutional and Historical Conditions Following a general orientation to her ethnographic work on cultural production, which straddles the fields of music, anthropology, digital media studies, sociology, and sound studies, Born focused us on her current work: academic and nonacademic electronic and computer art music in the UK, Europe, and Montreal. As with much of her other ethnographic work, this is a kind of dialectics of institutional and socio-musical change. To frame her work, she laid out the institutional and historical conditions that have led to the rise of interdisciplinary art-science in the UK. Born finds the seeds of interdisciplinary artistic research in the neoliberalization of the university. The emergence of the knowledge economy coupled with policies of measuring and evaluating the “impact” of research led to a crisis of value: what’s the use of art? Born draws attention to the UK’s Arts & Humanities Research Council’s Cultural Value Project as an example. This runs parallel with the assumed epochal shift to what has been called “Mode 2” knowledge production (see Gibbons et al.): scientifically autonomous and intra-disciplinary research has been replaced by context-based and accountable inter- and trans-disciplinary research. Born criticizes this theory for conceiving of this shift in “science” and “society” as unitary and homogenous: the particular genealogies of different disciplines, including the imbedded practices and motivations, are erased and unaccounted for. In one sense, Mode 2 could be viewed as exemplified in artistic research, and yet by working through Henk Borgdorff’s analysis of artistic research and Mode 2 knowledge production, Born is left with his conclusion that the central experiential component, that is, the aesthetic experience, ultimately seems to escape not only conceptual and discursive articulation, but also the epistemic frame. The point is that these difficulties make clear the need to empirically discern and analyze the phenomenon of interdisciplinary research in its particular formations, which is exactly what she did with a team of ethnographers starting in 2004. Modes and Logics Based on some of her work for that project on art-science interdisciplinarity, which is generally created at the intersection of the arts, natural science, and technology, Born outlined, and then located art-science in relation to, three modes and three logics of interdisciplinarity. These modes are 1) integrative-synthesis, an additive mode that produces something like “multi-disciplinarity,” 2) subordination-service, a hierarchical mode that produces a master-servant relationship between disciplines, and 3) agonistic-antagonistic, a mode that seeks a break with the individual disciplines by transcending a mere sum or combination of them. Examples of this final mode include cybernetics, science and technology studies, and the medical humanities, as well as art-science. The logics are 1) the logic of accountability, which is concerned with public understanding and engagement, 2) the logic of innovation, which is concerned with things like economic growth and the creative economy, and 3) the logic of ontology, which is concerned with not just an epistemological shift, but an ontological shift in the very conception of the subject and object in research to something always already social and relational. That is, the object being studied shifts to something that emerges through particular practices and yet is something that “grow[s] more richly real as [it] become[s] entangled in webs of cultural significance, material practices, and theoretical derivations” (Datson, 13). This third logic is tied closely to the third mode, but all three logics are entangled in interdisciplinary attempts.  This typology of the modes and logics of interdisciplinary research allows Born and her colleagues to argue that the shift from the scientific autonomy of Mode 1 knowledge production to the context-based and accountability of Mode 2 knowledge production is an insufficient model for understanding the complexities of interdisciplinary research. When disciplinary assemblages align with the agonistic-antagonistic mode and logic of ontology, constellations of practices, methodologies, and sites of application can form objects and produce effects that are irreducible to the demands of context and accountability; what is produced by these assemblages is not merely something innovative for the knowledge economy or politically/socially/economically instrumental. That is, new fields like the medical humanities and art-science do inter-disciplinary work that is as autonomous as intra-disciplinary work. This claim has a number of consequences for how these interdisciplines are maintained, managed, and evaluated by the various institutional powers that fund and support them. Genealogies Born then highlighted her 2006-7 study of art-science research in the UK and the US, where she focused on the Arts Computation Engineering (ACE) graduate program at UC Irvine. Perhaps the most fundamental differences she found between the UK and US examples were the institutional and employment conditions, the particular and historically contingent arrangements of power and capital, which dramatically shaped the interdisciplinary possibilities of art-science. The funding schemes in the UK work more on a program and grant basis, which means art-science is produced in the subordination-service mode through the logics of accountability and innovation, meaning that labor is divided, and art often serves as public science engagement or as experimental research itself. The US, on the other hand, may have a corollary in grant-funded arts and innovation studios, but also has produced the UC Irvine example, where the interdisciplinary program was suspended between three different schools: arts, computer science, and engineering. This model of long-term sustainable funding and the radical entanglement of traditionally separate concerns like conceptual art, AI, and human agency, afforded the possibility of a kind of transcendence or sublation of labor divisions. Art-science here operated beyond the logics of accountability and innovation, beyond a basic contribution to public knowledge and the knowledge economy; it operated according to the logic of ontology in that it created new subject-object relations. Born recounted how the seminars pulled from scholarship in not only computer science, cybernetics, conceptual art, and art and technology studio labs, but also critical and feminist theory and science and technology studies. This synthesis of literature from a multiplicity of genealogies allowed for what Born calls a shifting between epistemological and ontological registers, in which things like computational power, situated cognition, and digital representation of the analog world ran together with feminist critiques of power. So what did ACE actually do? Born presented a project by a member of the ACE program faculty, Beatriz da Costa, called PigeonBlog. It worked to track pollution in southern California by attaching pollution sensors to pigeons that would send live updates to an online map. The goal was to enlist the agential capacities of pigeons to elucidate the injustice of the production and distribution of pollution and the techniques used to measure the pollution by institutions in the area. The project was at once a conceptual art project, a feat of DIY engineering and computing, and a form of public engagement and environmental activism. [caption id="attachment_1939" align="alignnone" width="943"]

This typology of the modes and logics of interdisciplinary research allows Born and her colleagues to argue that the shift from the scientific autonomy of Mode 1 knowledge production to the context-based and accountability of Mode 2 knowledge production is an insufficient model for understanding the complexities of interdisciplinary research. When disciplinary assemblages align with the agonistic-antagonistic mode and logic of ontology, constellations of practices, methodologies, and sites of application can form objects and produce effects that are irreducible to the demands of context and accountability; what is produced by these assemblages is not merely something innovative for the knowledge economy or politically/socially/economically instrumental. That is, new fields like the medical humanities and art-science do inter-disciplinary work that is as autonomous as intra-disciplinary work. This claim has a number of consequences for how these interdisciplines are maintained, managed, and evaluated by the various institutional powers that fund and support them. Genealogies Born then highlighted her 2006-7 study of art-science research in the UK and the US, where she focused on the Arts Computation Engineering (ACE) graduate program at UC Irvine. Perhaps the most fundamental differences she found between the UK and US examples were the institutional and employment conditions, the particular and historically contingent arrangements of power and capital, which dramatically shaped the interdisciplinary possibilities of art-science. The funding schemes in the UK work more on a program and grant basis, which means art-science is produced in the subordination-service mode through the logics of accountability and innovation, meaning that labor is divided, and art often serves as public science engagement or as experimental research itself. The US, on the other hand, may have a corollary in grant-funded arts and innovation studios, but also has produced the UC Irvine example, where the interdisciplinary program was suspended between three different schools: arts, computer science, and engineering. This model of long-term sustainable funding and the radical entanglement of traditionally separate concerns like conceptual art, AI, and human agency, afforded the possibility of a kind of transcendence or sublation of labor divisions. Art-science here operated beyond the logics of accountability and innovation, beyond a basic contribution to public knowledge and the knowledge economy; it operated according to the logic of ontology in that it created new subject-object relations. Born recounted how the seminars pulled from scholarship in not only computer science, cybernetics, conceptual art, and art and technology studio labs, but also critical and feminist theory and science and technology studies. This synthesis of literature from a multiplicity of genealogies allowed for what Born calls a shifting between epistemological and ontological registers, in which things like computational power, situated cognition, and digital representation of the analog world ran together with feminist critiques of power. So what did ACE actually do? Born presented a project by a member of the ACE program faculty, Beatriz da Costa, called PigeonBlog. It worked to track pollution in southern California by attaching pollution sensors to pigeons that would send live updates to an online map. The goal was to enlist the agential capacities of pigeons to elucidate the injustice of the production and distribution of pollution and the techniques used to measure the pollution by institutions in the area. The project was at once a conceptual art project, a feat of DIY engineering and computing, and a form of public engagement and environmental activism. [caption id="attachment_1939" align="alignnone" width="943"] From Beatriz de Costa's PigeonBlog[/caption] The Fate of ACE and Its Implications The remainder of Born’s talk was mostly concerned with her insightful reflections on the points laid out above through numerous fascinating examples of music and art-science (for a sample check out Justin Yang’s Webwork I; NIME; Matilde Meireles and Rui Chaves’ Chasing ∞; Di Scipio’s Modes of Interference; Bob Ostertag’s Sooner or Later). The remainder of this blogpost offers a brief reflection on Born’s talk, starting with the end of the ACE program. ACE disbanded and the faculty in the program returned to teaching in more traditional disciplines (Beatriz da Costa tragically passed in 2012 due to cancer). Ironically, ACE’s advantage contained the mechanism of ACE’s fall: sustained funding brought with it the need for evaluation and the establishment of institutional value. Unable to create criteria that deemed ACE as having institutional value, UC Irvine shut down the program. The same neoliberalization of the university that created a culture of audit and evaluation both necessitates interdisciplinary work to justify the arts and humanities and negates the logic of ontology. As was established in the Q&A after Born’s talk, as well as at the final roundtable of the symposium, there are feasible, concrete steps that institutions can and should take in order to foster interdisciplinarity. Commitment to interdisciplinarity means a commitment to creating jobs for interdisciplinary scholars, so something like a revision of tenure procedures to better account for new kinds of work (something in which the FAA faculty showed great interest) is one of these possible steps. Furthermore, if we truly are committed to even attempting to meaningfully grasp or analyze inextricable, intractable, and incommensurable assemblages like racial capitalism, settler colonialism, and climate change, we might do well to continuously insist on institutional conditions that promote and foster the interdisciplinary logic of ontology. As we attempt to grapple with the spatial and temporal scales at which meaningful or sustainable change can occur, embracing and incubating interdisciplinarity and its radically new subject-object relations at the institutional level seems like a minimum requirement. For me, Born’s talk and the general reaction of the FAA faculty was a reminder to be sensitive to not only the potentialities afforded by the contradictions in neoliberalism and political economy, but also the local concrete actions capable of utilizing these contradictions.

From Beatriz de Costa's PigeonBlog[/caption] The Fate of ACE and Its Implications The remainder of Born’s talk was mostly concerned with her insightful reflections on the points laid out above through numerous fascinating examples of music and art-science (for a sample check out Justin Yang’s Webwork I; NIME; Matilde Meireles and Rui Chaves’ Chasing ∞; Di Scipio’s Modes of Interference; Bob Ostertag’s Sooner or Later). The remainder of this blogpost offers a brief reflection on Born’s talk, starting with the end of the ACE program. ACE disbanded and the faculty in the program returned to teaching in more traditional disciplines (Beatriz da Costa tragically passed in 2012 due to cancer). Ironically, ACE’s advantage contained the mechanism of ACE’s fall: sustained funding brought with it the need for evaluation and the establishment of institutional value. Unable to create criteria that deemed ACE as having institutional value, UC Irvine shut down the program. The same neoliberalization of the university that created a culture of audit and evaluation both necessitates interdisciplinary work to justify the arts and humanities and negates the logic of ontology. As was established in the Q&A after Born’s talk, as well as at the final roundtable of the symposium, there are feasible, concrete steps that institutions can and should take in order to foster interdisciplinarity. Commitment to interdisciplinarity means a commitment to creating jobs for interdisciplinary scholars, so something like a revision of tenure procedures to better account for new kinds of work (something in which the FAA faculty showed great interest) is one of these possible steps. Furthermore, if we truly are committed to even attempting to meaningfully grasp or analyze inextricable, intractable, and incommensurable assemblages like racial capitalism, settler colonialism, and climate change, we might do well to continuously insist on institutional conditions that promote and foster the interdisciplinary logic of ontology. As we attempt to grapple with the spatial and temporal scales at which meaningful or sustainable change can occur, embracing and incubating interdisciplinarity and its radically new subject-object relations at the institutional level seems like a minimum requirement. For me, Born’s talk and the general reaction of the FAA faculty was a reminder to be sensitive to not only the potentialities afforded by the contradictions in neoliberalism and political economy, but also the local concrete actions capable of utilizing these contradictions.