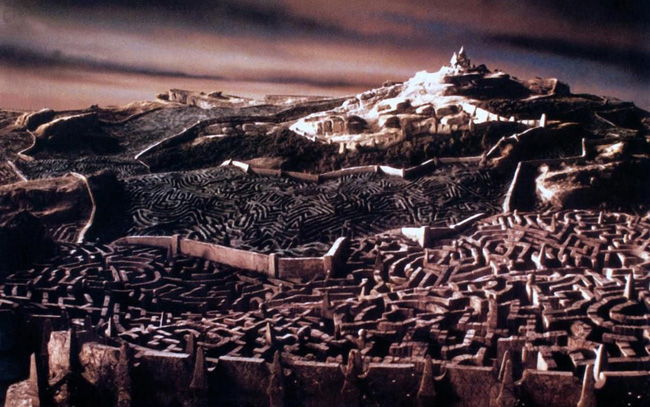

[On January 18th, the Unit for Criticism & Interpretive Theory hosted the lecture “'Interior Frontiers:' As Political Concept, Diagnostic, and Dispositif'” by Nicholson Distinguished Visiting Scholar Ann Laura Stoler (New School). Below is a response to the lecture from Mark E. Frank (East Asian Languages and Cultures).] Thinking with StolerWritten by Mark E. Frank (East Asian Languages and Cultures) “This moment is one for which we should have been prepared.” From the podium at Knight Auditorium and in the global shadow of the far right, Ann Laura Stoler delivered a lecture for the age of Trump and Le Pen, rhetorically migrating between continents but often dallying in the French milieu she has inhabited for much of her life. The evening lecture landed like a reconnaissance report by an agent whose self-directed assignments have seen her dialoguing with philosophers and “hanging out” with the Front National. It was an alert that we have arrived in an era when the political concepts and categories on which social theorists have honed their skills “may seem inadequate” as she put it—but more importantly, it was a clarion call to participate in the “conceptual labor” needed to move on, and a demonstration of what that might look like. This moment was one for which I should have been prepared. I came to see Stoler the historical anthropologist, the author of books like Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power and Along the Archival Grain from which I have borrowed turns of phrase in an effort to—as Stoler would say disapprovingly—“authorize” my theoretical framework. But what we got on Thursday was Stoler the philosophe, Stoler the theoretician who recoils from theory. For if, as Barbara Carnevali contends, philosophy “functions under long, frustrating timings” while theory is “quick, voracious, sharp, and superficial,” then Stoler is squarely on the side of philosophy. Her task as she identified on Thursday was “to discern the work we do on concepts and that concepts exert on us.” “I avoid theory,” she elaborated in her seminar on Friday. “I like thinking instead of concept work.” Concept work, concept labor... Again and again, Stoler communicated these imperatives through her dictum and her often burdened comportment, underscoring the point that meaningful critique is by necessity an onerous, laborious process. The goal is not to cite some Foucault here and Derrida there in an attempt to authorize our claims, but rather, to engage them at length, to think with them. On Thursday evening, she was thinking with the philosopher Étienne Balibar, whose notion of frontières intérieures—rendered in English as “interior frontiers”—she tracked through his papers from 1984 to 2015. The concept itself originated not with Balibar, but with the German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte, who, when Napoleon breached the external borders of the German Territories in 1804, proclaimed to his compatriots that “the first, original, and truly natural boundaries of states are beyond doubt their internal boundaries.” Fichte’s internal boundaries were not lines on a map, but the invisible bonds upon which national identities rely. Language, it seems was the quintessential example in Fichte’s imagination—the French could infiltrate German borders by strength of arms, but not the German language. Though American politics largely receded into the lecture’s background, the topic of boundaries within borders struck me as apt at a time when Trump’s slated border wall distracts from the instruments of exclusion within our borders. Fichte’s appeal to the notion of internal boundaries resonates in an unsettling way with the impulses that perpetuate ethnic and racial inequalities today, and so, as Stoler noted, it is difficult to comprehend why Balibar should seek to recuperate it in the late twentieth century. He was, after all, a sort of egalitarian, a onetime member of the Communist Party whose condemnation of the racism endemic to the Party saw him expelled. For Balibar, it would seem, the notion of frontières intérieures was valuable for its explanatory power. The external borders of states are insufficient to explain the enclosure of ethnic and national identities, which in fact are often cited as justifications for those borders; rather, it is the uncharted interior boundaries that paradoxically unite people by dividing them. Stoler clarified that if she has difficulty pinpointing the nature of Balibar’s interior boundaries, this is because in three decades of work he offers neither an analysis nor an explicit description of the term, even as he deploys it in ways that “exceed the prompt” in Fichte’s lectures. In attempting to interpret Balibar, Stoler took especial interest in his engagement with the writings of psychoanalyst André Green, who has emphasized the porous, composite, and multi-dimensional nature of boundaries in human experience. The skin, for example, is often taken to be the boundary of the individual body, and yet skin is porous; moreover, our points of contact with a person may involve a composite of eyes, ears, genitalia and other features. For Green, a line of demarcation is never in fact a line, but rather a permeable territory, a field of activity. Something in this formulation of internal boundaries resonated with Stoler’s experience of colonial history: it resembled the shifting and invisible criteria that perpetuated the comfort zones of the colonizers, that sustained the notion of whiteness and the prestige associated with it. In one of the lecture’s few turns to historical anecdote, Stoler related the story of a Dutch judge in colonial Saigon who determined that a métis boy should be tried as a native after citing a bevy of facts: the boy’s French was poor, he did not exhibit an appropriate disdain for Germans, and relationship to his “petit blanc” father stretched the bounds of propriety. Separating the boy from colonial identity was not an easily discernible or linear border, but an entire field of criteria representing the conditions of colonial comfort. Towards the end of the lecture, Stoler contemplated the appropriate spatial metaphor for interior frontiers. If they are not visible lines, perhaps they are hallways, or even “dark, infrared corridors” (recall that infrared light is invisible to the naked eye). For me, there was an irony in this search for a metaphor, because the “frontier” is itself a rich geographical metaphor worth mining. While the lecture employed the terms “frontier” and “border” more or less interchangeably, a contrast of those terms might have been productive. In the imagination of Frederick Jackson Turner the American frontier was not so much a line as a shifting field of activity, which was precisely what differentiated it from the fixed borders of Europe. The tension between complex and linear notions of the boundaries between states—frontiers, borderlands, borders—is what animates much of borderland studies today. It is also worth noting that the term “frontier” is a problematic translation of Balibar’s frontières intérieures: Consider, for example, that in the context of the European Union, frontières intérieures is a legal term designating the borders between states within the Union, and that the English rendering of this term is not “interior frontiers” but “internal borders”. By my understanding, that which the French call frontière translates most comfortably as “border” and not “frontier”; in fact, one might speculate that the Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors without Borders) are not doctors without frontiers, but doctors on the frontier of medical practice. Stoler’s analysis of frontières intérieures in the writings of Balibar was ultimately left unfinished in the sense that she was unable to reach a definitive resolution to some of the apparent contradictions in his thought, and in the sense that she ran over time and had to jettison the last section of the talk. It was an uncommonly inconclusive lecture, one that took both speaker and audience a little out of our depth, and I believe that was precisely the point—it was not so much an answer as an exercise in conceptual labor. Attendees pelted Stoler with the grandest sort of grand questions (What is the relationship between the individual and the polity? What kind of person do interior frontiers produce?) to which she responded with a scholarly mix of insight and humility (frequently, “I don’t know” or “I haven’t gotten that far”).  Figure 1. External and internal borders. From the film Labyrinth Interest in Stoler’s Friday workshop apparently exceeded the capacity of the first venue arranged by the Unit, which relocated to the executive boardroom of the Alice Campbell Alumni Center where we were seated around a table so comically enormous that it became the topic of much pre-seminar chatter—the table was a signifier of “white male power” joked Stoler (in the Orwellian sense that every joke is a tiny revolution). The theme of gender inequality was a latent presence that bubbled to the surface from time to time; at one point noting male appropriations of her ideas without citation, Stoler momentarily protested the “misogyny of citation”. But Stoler spent much more time communicating a vision of social critique that defies masculine norms in its embrace of uncertainty. She related that the hardest part of her career has not been finding answers, but rather coming up with questions, and specifically the kinds of questions for which she genuinely had no prior answer. She challenged the room to be frank in our writing about the questions for which have no ready answers, asking “do you hide them, which is a very male thing to do?” Stoler has made a career of critiquing racial and gender inequality, yet unspared in her remarks on Friday were what she described as the “cottage industries” of gender and race theory whose comfortable “PC” consensus can be anathema to true inquiry. Most seminar participants were graduate students, and so the latter portion of the seminar turned to the process of writing a thesis or dissertation. Stoler has authored six books and edited three more. Some of us wondered, whence her vision, her prolific energy? At all points in her responses she emphasized the painstaking nature of her work—a book that took decades to write, book projects that swallowed chapters from others, book projects that simply atrophied and died. Turning to her own experiences as a graduate student, Stoler related a sordid scenario: she became so stressed out by her dissertation that she somaticized it with migraines and indigestion, so unhappy with the final draft that she collated it backwards and deposited it that way, sharing it with no one outside her committee except her friend and mentor Jim Scott. For those of us, like me, at fisticuffs with our own dissertations, it was a regrettably familiar image. But it was also a message that curiosity is more important than surety, and that one can fall short of their own metric of perfection in the short term and still aspire to one day become someone as gutsy, luminous and impactful as Ann Laura Stoler.

Figure 1. External and internal borders. From the film Labyrinth Interest in Stoler’s Friday workshop apparently exceeded the capacity of the first venue arranged by the Unit, which relocated to the executive boardroom of the Alice Campbell Alumni Center where we were seated around a table so comically enormous that it became the topic of much pre-seminar chatter—the table was a signifier of “white male power” joked Stoler (in the Orwellian sense that every joke is a tiny revolution). The theme of gender inequality was a latent presence that bubbled to the surface from time to time; at one point noting male appropriations of her ideas without citation, Stoler momentarily protested the “misogyny of citation”. But Stoler spent much more time communicating a vision of social critique that defies masculine norms in its embrace of uncertainty. She related that the hardest part of her career has not been finding answers, but rather coming up with questions, and specifically the kinds of questions for which she genuinely had no prior answer. She challenged the room to be frank in our writing about the questions for which have no ready answers, asking “do you hide them, which is a very male thing to do?” Stoler has made a career of critiquing racial and gender inequality, yet unspared in her remarks on Friday were what she described as the “cottage industries” of gender and race theory whose comfortable “PC” consensus can be anathema to true inquiry. Most seminar participants were graduate students, and so the latter portion of the seminar turned to the process of writing a thesis or dissertation. Stoler has authored six books and edited three more. Some of us wondered, whence her vision, her prolific energy? At all points in her responses she emphasized the painstaking nature of her work—a book that took decades to write, book projects that swallowed chapters from others, book projects that simply atrophied and died. Turning to her own experiences as a graduate student, Stoler related a sordid scenario: she became so stressed out by her dissertation that she somaticized it with migraines and indigestion, so unhappy with the final draft that she collated it backwards and deposited it that way, sharing it with no one outside her committee except her friend and mentor Jim Scott. For those of us, like me, at fisticuffs with our own dissertations, it was a regrettably familiar image. But it was also a message that curiosity is more important than surety, and that one can fall short of their own metric of perfection in the short term and still aspire to one day become someone as gutsy, luminous and impactful as Ann Laura Stoler.