[On October 9, the Unit for Criticism & Interpretive Theory hosted a lecture by Jana Sawicki (Williams) entitled “Foucault, Biopolitics, and the Importance of Experiments in Living” as part of the Fall 2018 Modern Critical Theory Lecture Series. Below is a response to the lecture from Patrick Kimutis (English).] Jana Sawicki on “Foucault, Biopolitics, and the Importance of Experiments in Living” Written by Patrick Kimutis (English) Reading Foucault as a scholar-activist can be an experience as frustrating as it is eye-opening. If we accept his insight that power is not merely a repressive tool exerted downwards from the top, but rather is a force that characterizes all social relations and interactions, the path to a more liberatory society appears before us not as a straight line but a winding road fraught with detours, dead-ends, and backtracking. Even if the long-awaited revolution were to come, Foucault asks, aren’t we likely to create as many new problems and injustices as we solve? [caption id="attachment_1838" align="aligncenter" width="443"] Fig. 1. Foucault and Chomsky debate in 1971. If you’re frustrated with Foucault, you’re at least in good company. Source.[/caption] For this reason, Foucault’s writings may feel vexing, even counterproductive, to activists—Noam Chomsky once said that for all his concern about power, Foucault actually ended up reinforcing it more than undermining it. Foucault, we might conclude, is great at pointing out problems, but has much less to say when it comes to what to do about them. In her lecture, “Foucault, Biopolitics, and the Importance of Experiments in Living,” however, Professor Sawicki provided a different understanding of Foucault, someone she claims was “concerned with ethics from the beginning.” Foucault, Professor Sawicki argues, may not provide us with answers, but he does lay out a method by which we may undertake our own “experiments of living” in search of the good—or at least better—life. This Foucauldian method begins when we suspend a taken-for-granted concept, like madness or sexuality, and turn to the archive to see how it emerges and what dispositifs are brought to bear on it. A dispositif, often translated as “apparatus,” is a “heterogeneous ensemble” of discourses, laws, norms, and so forth that afford certain attitudes and behaviors while limiting others. The lecture hall, to use one of Professor Sawicki’s examples, makes it easier for a large group of people to listen to one individual at the same time it makes multiple small-group discussions more difficult. What Foucault finds in the archive, then, is that things that we take as a given are historically contingent, and thus not fixed—we can change them in order to emphasize or eliminate certain affordances or constraints. [caption id="attachment_1837" align="alignnone" width="640"]

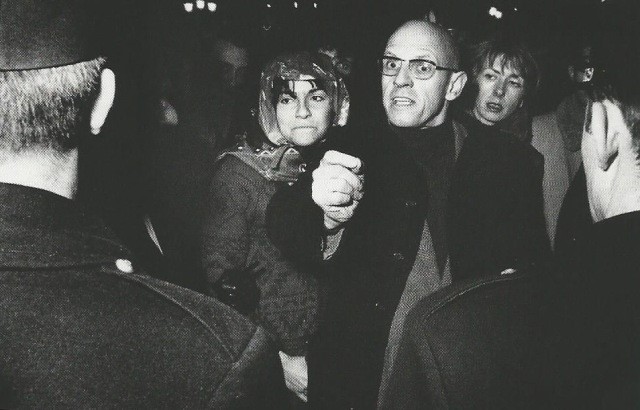

Fig. 1. Foucault and Chomsky debate in 1971. If you’re frustrated with Foucault, you’re at least in good company. Source.[/caption] For this reason, Foucault’s writings may feel vexing, even counterproductive, to activists—Noam Chomsky once said that for all his concern about power, Foucault actually ended up reinforcing it more than undermining it. Foucault, we might conclude, is great at pointing out problems, but has much less to say when it comes to what to do about them. In her lecture, “Foucault, Biopolitics, and the Importance of Experiments in Living,” however, Professor Sawicki provided a different understanding of Foucault, someone she claims was “concerned with ethics from the beginning.” Foucault, Professor Sawicki argues, may not provide us with answers, but he does lay out a method by which we may undertake our own “experiments of living” in search of the good—or at least better—life. This Foucauldian method begins when we suspend a taken-for-granted concept, like madness or sexuality, and turn to the archive to see how it emerges and what dispositifs are brought to bear on it. A dispositif, often translated as “apparatus,” is a “heterogeneous ensemble” of discourses, laws, norms, and so forth that afford certain attitudes and behaviors while limiting others. The lecture hall, to use one of Professor Sawicki’s examples, makes it easier for a large group of people to listen to one individual at the same time it makes multiple small-group discussions more difficult. What Foucault finds in the archive, then, is that things that we take as a given are historically contingent, and thus not fixed—we can change them in order to emphasize or eliminate certain affordances or constraints. [caption id="attachment_1837" align="alignnone" width="640"] Fig. 2. Foucault confronts the police during a protest in 1972. Source.[/caption] And this extends not just to the external forces we encounter in the world but to ourselves, our very subjectivity. For Foucault, ethics are primarily a self-relation, so not only can we change ourselves, if we want to change the world we ought to start by doing so. “The role of Foucault,” Professor Sawicki said, “is to teach us that we are freer than we feel.” The frustration that I identified early, then, may stem from the fact that Foucault proves unwilling to tell us what to do with that freedom. The onus is on us to be, as Professor Sawicki put it, inventors, constantly trying out new experiments in living and forming “communities of resistance” which seek to identify and remove unnecessary constraints on what people may choose as a good life. These experiments will necessarily always be incomplete, demanding constant revision, as we will find that in attempting to do away with some constraints we may inadvertently create others. But then again, as Professor Sawicki noted, that is exactly how Foucault conceived of his own work. “I don't write a book so that it will be the final word,” he said, “I write a book so that other books are possible, not necessarily written by me.” Indeed, the way his work has been taken up and taken in new directions by feminist and postcolonial theorists, such as Penelope Deutscher and Ann Stoler, as well as Professor Sawicki herself, is evidence that the incompleteness of our experiments need not be seen as something to regret, but rather celebrated. To paraphrase Beckett, our experiments in creating a better life and a better society will fail—but if we keep trying, we may at least hope to fail better.

Fig. 2. Foucault confronts the police during a protest in 1972. Source.[/caption] And this extends not just to the external forces we encounter in the world but to ourselves, our very subjectivity. For Foucault, ethics are primarily a self-relation, so not only can we change ourselves, if we want to change the world we ought to start by doing so. “The role of Foucault,” Professor Sawicki said, “is to teach us that we are freer than we feel.” The frustration that I identified early, then, may stem from the fact that Foucault proves unwilling to tell us what to do with that freedom. The onus is on us to be, as Professor Sawicki put it, inventors, constantly trying out new experiments in living and forming “communities of resistance” which seek to identify and remove unnecessary constraints on what people may choose as a good life. These experiments will necessarily always be incomplete, demanding constant revision, as we will find that in attempting to do away with some constraints we may inadvertently create others. But then again, as Professor Sawicki noted, that is exactly how Foucault conceived of his own work. “I don't write a book so that it will be the final word,” he said, “I write a book so that other books are possible, not necessarily written by me.” Indeed, the way his work has been taken up and taken in new directions by feminist and postcolonial theorists, such as Penelope Deutscher and Ann Stoler, as well as Professor Sawicki herself, is evidence that the incompleteness of our experiments need not be seen as something to regret, but rather celebrated. To paraphrase Beckett, our experiments in creating a better life and a better society will fail—but if we keep trying, we may at least hope to fail better.