[Below Joseph Swenson, a grad student affiliate in Philosophy and recipient of a Unit for Criticism travel grant last fall, writes about his conference paper on Dewey's theory of aesthetic experience]

[Below Joseph Swenson, a grad student affiliate in Philosophy and recipient of a Unit for Criticism travel grant last fall, writes about his conference paper on Dewey's theory of aesthetic experience]Experience in Context: Revisiting Dewey

Written by Joseph Swenson (Philosophy)

In October 2009 I presented a paper at the 67th Annual Meeting for the American Society for Aesthetics in Denver, Colorado. I had never presented a paper at this particular society and so I will admit I felt a bit giddy upon arrival—whether that giddiness was due to an atmosphere of anticipated intellectual intensity or simply a mile-high atmosphere slightly deprived of oxygen, I do not know.

But what I do know is that these engagements are always exciting for grad students. You get to meet some of those theorists you spent all that time reading and discussing in hushed, reverent tones in the back corners of Champaign coffeehouses. You also get to check out whether these people are as good in person as they are on paper. You even occasionally get to notice that they are human beings: that is, you notice things like they are just as capable of drinking one too many glasses of wine at a reception as anybody else and they stand just as much of a chance of spilling mustard all over their shirts from those weird conference hors d’oeuvres as you do. Most of all, you are pleasantly surprised that they are often quite friendly and even remember how important conferences like these are for those of us still early in our careers.

While the ASA is primarily a philosophical organization, it was nice to see a number of different presenters from different fields on the conference schedule. I attended a lot of good papers ranging from technical questions about the ontology of art to Jane Adam’s contribution to

pragmatist aesthetics. My particular paper was an attempt to defend the U.S. philosopher John Dewey’s account of aesthetic experience against the charge that Modern Art has made it obsolete.

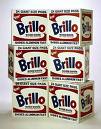

pragmatist aesthetics. My particular paper was an attempt to defend the U.S. philosopher John Dewey’s account of aesthetic experience against the charge that Modern Art has made it obsolete.The idea behind this Modernist claim is that works like John Cage’s moments of performative silence, Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes, and, above all, the granddaddy of all problematic Modern works—Duchamp’s Fountain—cannot be incorporated into traditional accounts of aesthetic experience. Why? Well, perhaps the most basic reason is that an ordinary urinal and Duchamp’s urinal appear to be experientially identical to one another and so one is forced into the rather weird inference that either both are objects of aesthetic experience or that neither is. Since most people do not want to consider their daily forays into the restroom on the same qualitative plane as their enjoyment of a painting by Caravaggio, many philosophers in the 20th century began to reject the concept of aesthetic experience when talking about Modern art particularly, and even in regard to art generally.

Perhaps this rejection is justified for many traditional accounts of aesthetic experience that still cling to a rather narrow and empirical conception of what "experience" entails. Dewey’s account, however, is hardly subject to such problems of narrowness; and so I pleaded with my audience not to lump him together with traditional accounts of aesthetic experience. One of the great benefits of Dewey’s theory in comparison to such traditional theories is that Dewey is contextual to the core. Experience always takes place in a context and that context is not only comprised of a physical environment but also a context of history, culture, various normative schemes, and even the context of one’s own personal narrative. If this idea is taken seriously, or so I argued, then there are quite distinct contextual differences between our experience of Duchamp and our experience of a restroom. Duchamp’s work is able to be experienced aesthetically not by virtue of some extra-empirical property it possesses which makes it art, but because of the evaluative attitudes it invokes by virtue of its contextual placement.

To put this in different language,it might very well be the case that modernity and techniques of reproduction can deprive artworks of their "aura" (as Walter Benjamin famously argued), but we should not forget that "aura" can just as easily be re-instituted by their re-contextualization within different normative contexts and evaluative schemes. Why even something as drab as a urinal can become something it could never have been prior to its re-contextualization: shocking, revolutionary, inspirational, voted by many to be the most significant work of art in the 20th century.

I, for one, take some solace in the redemptive idea that any chunk of the world, in principle, can become an object of aesthetic experience. If any of you, like me, happen to have a number of such "chunks" squirreled away in various drawers and boxes for sentimental reasons, the broader practical implications of this kind of argument hopefully go beyond the experiential redemption of a urinal and towards a richer conception of what it means to say that we value something.