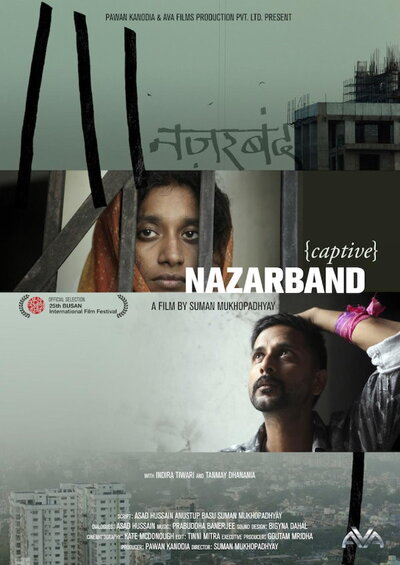

Suman Mukhopadhyay, the eminent film director and thespian from West Bengal, India, screened his latest release Nazarband (Captive/2020), a loose cinematic adaption of a short story by Ashapurna Devi, at Temple Hoyne Buell Hall on 15th September 2022. This Hindi film tracks the trajectories of two convicts, Vasanti Mahato (Indira Tiwari) and Chandu (Tanmay Dhanania), shortly after being freed from incarceration. Together, despite initial hiccups, they traverse the length and breadth of Kolkata and its hinterlands, to seek a new start, or perhaps a reunion with the past. The screening was followed by a Q&A session.

The first half of Nazarband alludes to the Bengali-language film, Sthaniya Sambaad (Spring in the Colony/2009/dir. Moinak Biswas), where Suman played the role of a middle-class intellectual who accompanied a young poet in his quest to find love in a city being rapidly transformed by the encroachment of global capital. But unlike Sthaniya Sambaad, Nazarband shifts its focus from the coveted milieu of the educated urban Bengali gentry to concentrate on the secret lives of two culturally, linguistically, and economically marginalized characters striving to survive and find meaning in the ruthless megalopolis. Therefore, instead of the glamorous enterprises of Park Street and erstwhile refugee colonies in South Calcutta infiltrated by the parvenu (that operate as the setting in Sthaniya Sambaad), the film takes us to the dark, dingy underbellies of Kolkata where illegal deals are carried out and pimps masquerade as social workers in brothels fronting as massage parlours. The transformation of the city into a neoliberal den of corruption has also advanced. The roads are draped in blue and white (a controversial decision by the ruling party to allegedly syphon public funds), an extravagant shopping mall has taken the place of a factory, and more skyscrapers are coming up on the virgin land of New Town spreading its wings at the city’s periphery. The recurring motif of building construction seems to symbolize how the past is being demolished to make way for the ‘new’. Wide-angle shots of kites and crows flying in aimless circles during twilight hint at patterns of confusion and dilemma shaping the narrative arcs of Vasanti and Chandu.

Vasanti worked as a housemaid in a rich Marwari family before being implicated in a crime that she did not commit. Chandu, in contrast, made a living by taking the fall for the sins of others. Upon serving her time, Vasanti, hoping to reunite with her son, is disappointed to not see her husband outside the prison to receive her. Desperate to track the current whereabouts of her family, she finds an unlikely ally in Chandu who feigns friendship to traffic her for a hefty commission. But after being ditched and humiliated by his boss, Bablooda (suggestively a tycoon with strong connections in the ruling party), Chandu rescues Vasanti; this time to sell her to another shady merchant for a ticket to start afresh abroad. But he aborts his mission after a twist and turn of events that help him understand that a mutually symbiotic relationship of sympathy and compassion has developed between them. Vasanti travels to her village in the adjacent state Jharkhand to discover that her husband has remarried another woman who is mothering her son, Hira. As both Vasanti and Chandu’s initial plans of living their post-prison life fall apart, they understand that they are the only ones left for each other. After passionately making love in a truck on their overnight journey back to Kolkata, they brace themselves together for a moment at the face of an uncertain future together. During the question-answer session moderated by Prof. Anustup Basu (also a co-screenplay writer of the film) that ensued Suman clarified that Nazarband was primarily a film about the lives of the Hindi-speaking lower class populating the slums of Kolkata that hardly feature as protagonists in the literature and cinema produced in West Bengal. And that trajectory is defined by a ‘subliminal’ presence of religiosity and right-wing politics in a changing cityscape.

Albeit it could be remarked that the narrative’s focus is on the predicaments of two members of otherized demography in Kolkata rather than being an explicit commentary on how the city has been transformed by Hindutva and populist politics in recent years, religion features both a prominent symbol and a material presence. In one of the establishing shots, one encounters a worn-out idol of a Goddess deserted under a tree after worship, closely resonating with Vasanti’s dejection. Subsequently, as Chandu navigates through the squalor of the potters’ hub in North Kolkata to meet one of his unscrupulous bosses, the mise en scène presence new idols being sculpted for the festival ahead forecasts the emergence of a camaraderie between them that would follow several bouts of betrayal and rejection. Nazarband is set in the rainy Bengali month of Sravan (July-August) when thousands of devotees flock to the sacred temple in Tarakeswar. Chandu and Vasanti, still fugitives from Bablooda’s henchmen, decide to camouflage as pilgrims seeking the blessings of Shiva, the ruling deity of creation, protection, and destruction in Hindu mythology. However, their views toward religion do not tally. While Chandu retains his skepticism, Vasanti turns out to be a firm believer who engages in a series of rituals to offer her prayers. While taking a dip together in the holy river, Chandu sarcastically remarks that he has been cleansed of his past sins. That moment marks a turning point in the plot; Chandu decides against trafficking Vasanti.

The cultural politics of Nazarband manifests at the intersection of greed and religion. On the one hand, the conjunction of electoral politics and neoliberal capital has transformed organized religion into a business, as well as an instrument of governance, by pushing back against the secular and non-religious practices of public life. Chandu’s character demonstrates how religiosity could be manipulated as a strategy to survive. Vasanti’s faith, on the other hand, is reminiscent of Karl Marx’s observation on how religion exists as “the sigh of the oppressed creature”. In the post-communist ethos of West Bengal marked by the absence of vanguards that could have stood by her, she clings on to religion to “protest against (her) real suffering” embracing it as if it is the “heart of (her) heartless condition”.

Screened coincidentally a couple of days after Jean-Luc Godard’s demise, Suman mentioned how his film deploys some of the techniques arguably attributed to the iconic French auteur. The use of handheld cameras (that bring about jerks) to shoot sequences in a crowded metropolis, as well as the juxtaposition of visual metaphors that give meaning to an otherwise chaotic universe, makes one compare the chase scenes in Nazarband with their counterparts in Breathless (1960). The pace of the narrative is slow but consistent; the assemblage of visuals depicting lust, violence, cruelty, apathy, and helplessness evoke a combined affect of irritation, disturbance, and contemplation. Suman plays with time and continuity. Recollections do not happen through flashbacks. The protagonists finally excavate what is worth living for after they step out of the thresholds of the city. A sudden wide-angle transition to the abundance of greenery in the countryside after a series of close-ups in the dark, claustrophobic alleys in North Kolkata insinuates an internal transformation of the characters on an escapade from the city. But Nazarband (literally meaning surveilled in Hindi), true to its English title ‘captive’ establishes that although the city could be left, it cannot be escaped. It must be re-entered and negotiated. The poetry of urban life is dissolved in a quagmire of temptation, conflict, and salvation.

The event was well-attended by enthusiastic students and faculty belonging to different disciplines, ranging from architecture to literature to media studies. It would not be wrong to hope that they returned with considerable food for thought after spending a rewarding evening in the company of an acclaimed personality and his creation.