[Faith Wilson Stein, a graduate student in Comparative Literature, is the author of the next in our multi-authored series of posts on the fourth season of Mad Men, which anticipated the March 2013 release of MAD WORLD: Sex, Politics, Style and the 1960s by Duke University Press.]

[Faith Wilson Stein, a graduate student in Comparative Literature, is the author of the next in our multi-authored series of posts on the fourth season of Mad Men, which anticipated the March 2013 release of MAD WORLD: Sex, Politics, Style and the 1960s by Duke University Press.]"GET RID OF IT"

Written by Faith Wilson Stein (Comparative Literature)

The tenth episode of Mad Men’s fourth season, “Hands and Knees,” has, as in previous years, depicted various characters’ relationships (the filial in particular) coming to a reckoning. In Season One’s “Long Weekend,” Roger’s heart attack brings him back to his wife and daughter, while it drives Don to seek comfort with Rachel, with whom he shares some of the seedier details of his background, telling her, “You know everything about me.” Meanwhile, Betty, unaware of her husband’s affair with the department store heiress, is chafing at the presence of a new girlfriend in her father’s life. Season Two’s “The Inheritance” brings Betty and Don to her father’s house, their marriage seemingly set to end, only for the pain and stress of Gene’s post-stroke condition to prompt an assignation that results in pregnancy and a temporary forestalling of divorce. In last year’s “The Color Blue,” the secretive plan to sell Sterling Cooper to another agency is revealed, while one of the show’s central points of narrative tension—the prospect of Betty’s discovering Don’s false identity—comes to a head.

This week’s episode revisited several of these markers—Roger’s heart problems; a serious threat to Sterling Cooper’s existence; an unintended and inconvenient pregnancy; and, of course, Don’s possible exposure as a fraud and deserter. In hurtling forward with various plotlines, the episode made up for the narrative pauses taken in “The Suitcase” (Season 4, Episode 7) and “The Summer Man” (Season 4, Episode 8), mood pieces that featured more overtly artistic gestures–such as the appearance of a spectral Anna and Don’s voiceover—than the show had previously indulged. At the same time, the near total absence of actual “ad talk” (as well as Peggy) would seem to stress interpersonal thematics over the more philosophical consideration of advertising’s harnessing of creativity in order to invent and stoke desire. Still, several instances of parallelism throughout the episode underscore that, as always, the viewer is being sold something: the show itself as a product, yes, but also, (as Don once told Peggy, and as last week’s post on wordplay also noticed), “You, feeling something. That’s what sells.”

The opening exchange between Roger and Joan—she practical as ever while he indulges in his own personal salesmanship (whether “the tenderloin of your distress” is a greeting she finds charming is anyone’s guess)—establishes the episode’s central theme: the power of fatherhood, from the literal to the symbolic, and the need to grapple with it. We see Don winning back Sally’s affection with tickets to the Beatles concert at Shea Stadium. (One hopes that despite her precocity, at 10 years old she has not yet developed a sense of irony, acute or otherwise). This explicit reference to the “British Invasion” is overdue for a show so richly packed with cultural history, and it is cheekily followed by an English incursion on a much smaller scale, as Lane, still holding the gifts with which he’d hoped to charm his own child, is surprised by his imperious father.

The opening exchange between Roger and Joan—she practical as ever while he indulges in his own personal salesmanship (whether “the tenderloin of your distress” is a greeting she finds charming is anyone’s guess)—establishes the episode’s central theme: the power of fatherhood, from the literal to the symbolic, and the need to grapple with it. We see Don winning back Sally’s affection with tickets to the Beatles concert at Shea Stadium. (One hopes that despite her precocity, at 10 years old she has not yet developed a sense of irony, acute or otherwise). This explicit reference to the “British Invasion” is overdue for a show so richly packed with cultural history, and it is cheekily followed by an English incursion on a much smaller scale, as Lane, still holding the gifts with which he’d hoped to charm his own child, is surprised by his imperious father. In this three-part beginning, the issue of Roger’s paternity (pun regrettably intended) is a problem to be eliminated; Don’s shoddiness as a father is at once ameliorated and confirmed with his bribery; and Lane is denied the chance to act like a doting father and is instead put in the position of humbled son. (Note as well how the revelation that Roger “inherited” the Lucky Strike account, and his rolodex of dead clients, further attests to his shortcomings as a procurer of accounts in his own right.)

In this three-part beginning, the issue of Roger’s paternity (pun regrettably intended) is a problem to be eliminated; Don’s shoddiness as a father is at once ameliorated and confirmed with his bribery; and Lane is denied the chance to act like a doting father and is instead put in the position of humbled son. (Note as well how the revelation that Roger “inherited” the Lucky Strike account, and his rolodex of dead clients, further attests to his shortcomings as a procurer of accounts in his own right.)The transition to the meeting with North American Aviation and the encounter it entails with the Department of Defense sets up the episode’s figurative filial tensions. Pete, abandoned by Don in California back in Season 2, has nurtured the account “from cocktail napkins to four million dollars”; and yet, when the threat is raised of Don’s leaving the agency (indeed, leaving the life of “Don Draper” entirely), Pete, like Joan, has to “get rid of it.” (The added irony, of course, is that Pete is himself an expectant father as a very pregnant Trudy can't but remind him.) While Don has previously acted as a withholding father figure to Pete, the looming threat of government sanction (not to mention Lee Garner Jr.’s sudden removal of SCDP’s Lucky Strike lifeline) is a form of paternalistic punishment far more frightening than mere interpersonal resentments.

For Don, the possibility of needing to relinquish the responsibilities of “Don Draper”—the claims of paternity in both literal and figurative senses—is perhaps his most basic fear and desire. Having abandoned “Dick Whitman” and all his ties and obligations, Don is at once the inheritor of the real Lieutenant Draper’s legacy as well as the ultimate self-made man: the “father” of his own identity.

But the professional life Don has built for himself once again threatens the persona it has bolstered and vice versa. The Department of Defense agents who question Betty are investigating possible Communist links, and yet, while Don is no socialist, their line of inquiry cuts to the very heart of her fractured relationship with her ex-husband, crystallizing his character and the central questions of the show. Is Don Draper a man of “integrity”? Is he “loyal”? Harking back to this season’s opening line (“Who is Don Draper?”), the G-men ask Betty if there is any reason to suspect that her former husband “isn’t who he says he is.” Is there any answer that Betty could have given to those questions that wouldn’t, on one level or another, be untrue?

In Season One, Roger’s cardiac distress precipitated Don’s seeking confession and comfort with a woman; this time, however, the transition requires the viewer to connect the dots as the scenes shift. For the second time this season, Don is ill in front of a woman, left vulnerable and exposed. But whereas Don’s revelations to Peggy were limited, his confession to Faye divulges more of his true history, linking physical purging to a disgorging of his sins. Nonetheless, the intimacy it would seem to create between him and Faye feels tenuous. By contrast, the other couples in the episode give the impression of greater stability, perhaps precisely because they do not share their secrets. Trudy, to whom Pete does not tell the story of Don’s identity, assures him, “Everything’s good here.” The line recalls Betty’s statement to Henry at the end of “The Summer Man”: “We have everything.” Although Betty doesn’t tell Henry the full truth regarding the Department of Defense’s questions about Don, she appears content with Henry in the promise, however false, that there are no secrets between them.

In Season One, Roger’s cardiac distress precipitated Don’s seeking confession and comfort with a woman; this time, however, the transition requires the viewer to connect the dots as the scenes shift. For the second time this season, Don is ill in front of a woman, left vulnerable and exposed. But whereas Don’s revelations to Peggy were limited, his confession to Faye divulges more of his true history, linking physical purging to a disgorging of his sins. Nonetheless, the intimacy it would seem to create between him and Faye feels tenuous. By contrast, the other couples in the episode give the impression of greater stability, perhaps precisely because they do not share their secrets. Trudy, to whom Pete does not tell the story of Don’s identity, assures him, “Everything’s good here.” The line recalls Betty’s statement to Henry at the end of “The Summer Man”: “We have everything.” Although Betty doesn’t tell Henry the full truth regarding the Department of Defense’s questions about Don, she appears content with Henry in the promise, however false, that there are no secrets between them.Lane’s father, in an act of horrifying violence, brings his son to the “hands and knees” evoked in the title of the episode, commanding his child—who has fallen in love with a woman of color—to “put [his] home in order.” Despite the brutality of the moment, the truth of his admonishment rings clear: “Either here or there. You will not live in between.” Here or there, New York or London, Don or Dick, abased honesty or contented secrets. While Roger’s health might attest to the disadvantages of keeping damning information to oneself, the eventual exposure of everything is apparently no less messy and leaves one prostrate on the floor--seemingly destined to return to a previous state of reserved lies.

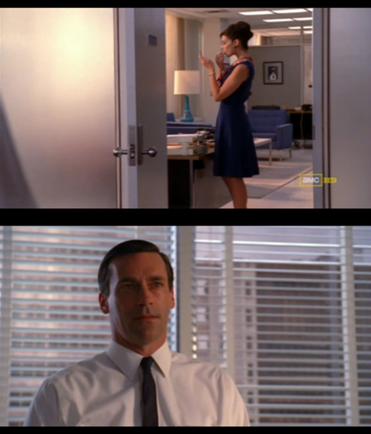

The episode nears its conclusion with Faye standing in Don’s open office doorway, uttering innocuous professionalisms to cover over the intimacies they had been sharing moments prior (even while their office romance is another secret Pete has discovered). Faye’s faked exit parallels Joan’s behavior with Roger in the opening scene and suggests that the brutal underside of their relationships – the need to abort what one has conceived and to vomit up the fundamental lie at the center of one’s life – bubble up beneath the faked detachment necessary to maintain the professional status quo.

The episode nears its conclusion with Faye standing in Don’s open office doorway, uttering innocuous professionalisms to cover over the intimacies they had been sharing moments prior (even while their office romance is another secret Pete has discovered). Faye’s faked exit parallels Joan’s behavior with Roger in the opening scene and suggests that the brutal underside of their relationships – the need to abort what one has conceived and to vomit up the fundamental lie at the center of one’s life – bubble up beneath the faked detachment necessary to maintain the professional status quo. Finally, through the open office door, we see Megan and, then, we see Don seeing Megan. Looking up from the Beatles tickets he had anxiously checked on throughout the episode, he stares at her, wearing a wholly inscrutable look. Is he in awe of her youth and ingenuousness, unencumbered by the knowledge of who he truly is? Is that then a source of lust? Would she tell him that everything is good here? Or if he told, would she promise that (as Anna told him in the third episode of this season), she knows everything about him, and still loves him? Does a relationship founded on truth hold the same appeal to Don that it once did, or does he desire guilelessness and the patched together resolution of a clerical error that appears to have been fixed?

Finally, through the open office door, we see Megan and, then, we see Don seeing Megan. Looking up from the Beatles tickets he had anxiously checked on throughout the episode, he stares at her, wearing a wholly inscrutable look. Is he in awe of her youth and ingenuousness, unencumbered by the knowledge of who he truly is? Is that then a source of lust? Would she tell him that everything is good here? Or if he told, would she promise that (as Anna told him in the third episode of this season), she knows everything about him, and still loves him? Does a relationship founded on truth hold the same appeal to Don that it once did, or does he desire guilelessness and the patched together resolution of a clerical error that appears to have been fixed?We close with the Beatles’ “Do You Want to Know a Secret” (a song they did not actually play at Shea Stadium), but it is an instrumental version. The episode is bookended with this legendary band, for whom young girls screamed as though instantly forgetting the mistakes of the men in their lives. Yet we do not hear the actual words entreating us to listen, asking if we want to know a secret.

The weight of knowing, the responsibility of taking ownership over those secrets, is perhaps too much to bear. Maybe we should get rid of it.