[This second of two final entries in our multi-authored series of posts on the fourth season of Mad Men, prior to publishing MAD WORLD: Sex, Politics, Style and the 1960s, is by Lilya Kaganovsky. The first post was written by co-editors Lauren Goodlad and Rob Rushing]

[This second of two final entries in our multi-authored series of posts on the fourth season of Mad Men, prior to publishing MAD WORLD: Sex, Politics, Style and the 1960s, is by Lilya Kaganovsky. The first post was written by co-editors Lauren Goodlad and Rob Rushing]"THE BLUE PILL"

Written by Lilya Kaganovsky (Slavic/Comparative Literature)

In 2008, six years after The Wire first aired on HBO, Film Quarterly published a review of the complete fourth season on DVD, which described (in a positive way) the show’s fans as junkies and the show as a drug. Fans come to video stores, wrote J. M. Tyree, jonesing for a hit, desperate for another dose of a show that missed its audience only by finding it (much like Proust suggests a good novelist does) after the fact, when its five (really four and a half) seasons were nearly over:

There is a growing cult around The Wire, although many of its members do not subscribe to HBO, appearing instead like junkies at their local video rental stores months after the original broadcasts, and helping the show continue its extraordinary afterlife.

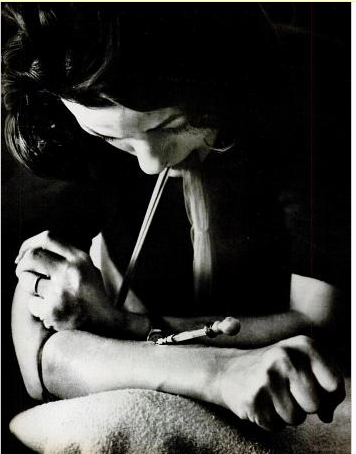

If Season 4 of Mad Men has been about anything, it has been about addiction. Cigarettes, alcohol, and sex appeared this season no longer bathed in the retrospective glow of nostalgia, but as vice, pure and simple, starting with Don’s masochistic sex with a prostitute in the first episode, and ending with Midge’s heroin addiction. As with so much television since the 1990s, and in the realist novel before that, smoking and drinking are used only to show weakness of character, a man (or woman) out of control. Pete, for example, who has been a much more upstanding citizen this season, doesn’t smoke and barely drinks, and the same goes for Henry Francis, as he holds his moral high ground against Betty’s fits of rage. “You need a drink? What are you, a wino? You need a drink?” he snarls during a memorable car ride home (“The Summer Man,” 4.8). No wonder Don vomits twice during this season: his very being is rejecting the thing he has become, while addiction itself is linked to cancer that eats away at you from the inside (another theme that begins with Anna Draper’s illness and ends with a possible anti-smoking campaign for the American Cancer Society).

If Season 4 of Mad Men has been about anything, it has been about addiction. Cigarettes, alcohol, and sex appeared this season no longer bathed in the retrospective glow of nostalgia, but as vice, pure and simple, starting with Don’s masochistic sex with a prostitute in the first episode, and ending with Midge’s heroin addiction. As with so much television since the 1990s, and in the realist novel before that, smoking and drinking are used only to show weakness of character, a man (or woman) out of control. Pete, for example, who has been a much more upstanding citizen this season, doesn’t smoke and barely drinks, and the same goes for Henry Francis, as he holds his moral high ground against Betty’s fits of rage. “You need a drink? What are you, a wino? You need a drink?” he snarls during a memorable car ride home (“The Summer Man,” 4.8). No wonder Don vomits twice during this season: his very being is rejecting the thing he has become, while addiction itself is linked to cancer that eats away at you from the inside (another theme that begins with Anna Draper’s illness and ends with a possible anti-smoking campaign for the American Cancer Society).But what, as Avital Ronell asks in Crack Wars, do we hold against the drug addict? What do we hold against the drug addict?

… that he cuts himself off from the world, in exile from reality, far from objective reality and the real like of the city and the community; that he escapes into a world of simulacrum and fiction. We disapprove of hallucinations. . . . We cannot abide the fact that his is a pleasure taken in an experience without truth.

Ex-stasis, going beyond/outside of yourself, the “high” of transgression. For pleasure to be what it is, says Ronell, it has to exceed a limit of what is altogether wholesome and healthy. Otherwise, “it’s something like contentedness, which can be shown to be in fact an abandonment of pleasure.”

Heroin is “like drinking 100 bottles of whiskey while someone licks your tits,” says Midge, poetically.

There has been some debate about what Mad Men has meant for its viewers. Its most vociferous critics have insisted that there’s something false about the show, that the emperor has no clothes, that Mad Men, like a variation of the Matrix, is a “world that has been pulled over our eyes to blind us from the truth.”

Morpheus: The Matrix is everywhere. It is all around us. Even now, in this very room… It is the world that has been pulled over your eyes to blind you from the truth.

Neo: What truth?

Morpheus: That you are a slave, Neo… After this, there is no turning back. You take the blue pill, the story ends, you wake up in your bed and believe whatever you want to believe. You take the red pill, you stay in Wonderland, and I show you how deep the rabbit hole goes. Remember: all I’m offering is the truth. Nothing more.

(“I want a third pill!” says Zizek about this particular form of forced choice. As an aside, we might note that the man dealing drugs here is called Morpheus, and that “truth” he is offering is a trip down the rabbit hole.)

Critics of the show cannot understand how others have become hooked, what keeps them coming back week after week asking for more. As one respondent to Jason Mittell’s post "On Disliking Mad Men" put it,

At first I was excited to see Mad Men. But my reaction was similar—a feeling of deep repulsion… I kept trying to sample it, hoping the drama/characters would “click.” When peers raved, I’d mutter something vaguely unenthusiastic, then have to listen to them “explain” that MM was really about the “crisis of masculinity” or some such.

Given “the horrendous peer pressure to love MM,” the same critic writes, we miss seeing the bad acting, the bad writing, the nonsensical characters with their inexplicable behavior. We are seduced by the set and costume design and so fail to notice that we are getting glamour without substance, surface without depth, simulacrum without truth. “Not only is it disingenuous,” she writes, “it’s repulsive.”

Season 4 of Mad Men ends with an inexplicable choice: in a moment of what can only be perceived as delusion or addiction, Don chooses Megan-the-secretary over Dr. Faye Miller. Surely he should know better by now! But the show, as we know, is not a Bildungsroman. Characters do not change or grow but, like addicts, repeat the same destructive acts because what they are addicted to is the fantasy itself. Faye offers Don a relationship “in the open.” She suggests that he can start trying to be a “person like the rest of us.” That he is a “type,” whose actions are known in advance. And Don even takes a step toward this new found “maturity” when he links his two names, Don and Dick, for Sally. And then he reverts, falls off the wagon, goes back for another hit. He proposes with another man’s ring, once again insisting on a fake identity over the real one. “I feel like myself when I’m with you,” Don tells Megan, “but—the way I always wanted to feel.”

Literature, cinema and television are about addiction. In order to be a good reader or a good viewer you have to allow yourself to be transported by the text, consumed by the fictions it offers. Children age 8, pediatric guidelines suggest, should have their TV viewing limited to an hour a day. Fiction offers us a way out of our daily lives, out of the monotony of existence, a way to move beyond the self. Ronell calls this “Narcossism”: our relation to ourselves structured and mediated by some form of addiction and urge. To get off any drug, she says, or anything that has been invested as an ideal object—something that you want to incorporate as part of you—precipitates a major narcissistic crisis.

Literature, cinema and television are about addiction. In order to be a good reader or a good viewer you have to allow yourself to be transported by the text, consumed by the fictions it offers. Children age 8, pediatric guidelines suggest, should have their TV viewing limited to an hour a day. Fiction offers us a way out of our daily lives, out of the monotony of existence, a way to move beyond the self. Ronell calls this “Narcossism”: our relation to ourselves structured and mediated by some form of addiction and urge. To get off any drug, she says, or anything that has been invested as an ideal object—something that you want to incorporate as part of you—precipitates a major narcissistic crisis.Season 4 has been precisely about this narcissistic crisis. It’s been about trying to get off drugs—cigarettes, alcohol, heroin, bad sex, living a lie. It hasn’t been pleasant to watch. It’s been as if the show itself is trying to de-cathect its viewers by suddenly refusing to occupy that position of “ideal object,” as if the show itself is trying to resist “the horrendous peer pressure to love MM.” In essence, “Blowing Smoke” was the final episode of season 4, the episode where all the myths and fantasies of “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” were seemingly rejected in favor of the “truth.” American Tobacco replaced by the American Cancer Society. Midge Daniels smoking pot replaced by Midge Daniels shooting up heroin.

But “Tomorrowland” is about something else. Let’s call it a “fresh start” because, like Don, we really only like the beginnings of things. There’s a wonderful episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer (“Normal Again” 6.17) in which Buffy is offered a choice similar to the one Morpheus offers Neo, that is, between taking the blue pill and waking up a slave to fantasy, or taking the red pill and seeing the “truth.” The choice offered Buffy in “Normal Again” is similar: go back to the fantasy world in which you are a superhero and all your friends have superpowers, or stay in the “real” world where your delusional fantasies are just that—a sign of addiction and mental illness. Neo chooses the red pill. (We disapprove of hallucinations, says Ronell. We cannot abide the fact that the addict’s pleasure is taken in an experience without truth.) Buffy chooses the blue.

But “Tomorrowland” is about something else. Let’s call it a “fresh start” because, like Don, we really only like the beginnings of things. There’s a wonderful episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer (“Normal Again” 6.17) in which Buffy is offered a choice similar to the one Morpheus offers Neo, that is, between taking the blue pill and waking up a slave to fantasy, or taking the red pill and seeing the “truth.” The choice offered Buffy in “Normal Again” is similar: go back to the fantasy world in which you are a superhero and all your friends have superpowers, or stay in the “real” world where your delusional fantasies are just that—a sign of addiction and mental illness. Neo chooses the red pill. (We disapprove of hallucinations, says Ronell. We cannot abide the fact that the addict’s pleasure is taken in an experience without truth.) Buffy chooses the blue. >Because to choose “reality” over “fantasy” is to give up on your desire. It means settling for contentment over jouissance, for Dr. Faye Miller over Megan. For the moment, Mad Men has pulled back from that particular edge, where it’s been heading all season long. The final coup belongs not to Don but to Peggy who not only singlehandedly breaks SCDP’s losing streak by signing a new client, but delivers one of the best lines of the entire season: “Well, I learned a long time ago to not get all my satisfaction from this job,” Joan tells her, in a moment of female bonding over men and a cigarette. “That’s bullshit!” says Peggy, exhaling smoke.

>Because to choose “reality” over “fantasy” is to give up on your desire. It means settling for contentment over jouissance, for Dr. Faye Miller over Megan. For the moment, Mad Men has pulled back from that particular edge, where it’s been heading all season long. The final coup belongs not to Don but to Peggy who not only singlehandedly breaks SCDP’s losing streak by signing a new client, but delivers one of the best lines of the entire season: “Well, I learned a long time ago to not get all my satisfaction from this job,” Joan tells her, in a moment of female bonding over men and a cigarette. “That’s bullshit!” says Peggy, exhaling smoke.