[The third in our multi-authored series of posts on Mad Men season 4, published before the publication ofMAD WORLD: Sex, Politics, Style and the 1960s (Duke University Press).]

[The third in our multi-authored series of posts on Mad Men season 4, published before the publication ofMAD WORLD: Sex, Politics, Style and the 1960s (Duke University Press).]"BAD NEWS"

Written by Lauren M. E. Goodlad (Director, Unit for Criticism/English)

There is a scene in the 1956 movie, The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, in which three men, one of whom is Thomas Rath (Gregory Peck), walk into a business meeting wearing nearly identical gray business suits. The film is referenced in Season 2 of Mad Men (Episode 9, “Six Month Leave”) when Jimmy Barrett spots Don and says, “Well, if it isn’t the man in the gray flannel suit.” Furious at Jimmy for telling Betty about his affair with Bobbie Barrett, Don answers the comedian with a punch in the face.

There is a scene in the 1956 movie, The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, in which three men, one of whom is Thomas Rath (Gregory Peck), walk into a business meeting wearing nearly identical gray business suits. The film is referenced in Season 2 of Mad Men (Episode 9, “Six Month Leave”) when Jimmy Barrett spots Don and says, “Well, if it isn’t the man in the gray flannel suit.” Furious at Jimmy for telling Betty about his affair with Bobbie Barrett, Don answers the comedian with a punch in the face.Despite some interesting parallels, Don’s story is very different from Rath’s. Although Rath is, like Don, a suburban commuter with a wartime secret, the threat he faces is the mass-marketed conformity of postwar America. This has never been a serious problem for Don who, from the start, has been something of a rock star: his well-tailored suits a mark of masculine panache, not corporate subordination. Then too, Rath saves his soul and his marriage by telling the truth about his past, and putting family before professional ambition. Needless to say this is not Don’s story. Indeed, Season 4 of Mad Men has, so far, been the tale of a man who loses everything after telling the truth.

As Don says to Anna Draper in Episode 3 (“The Good News”), the minute Betty “saw who I really was she never wanted to look at me again.” Eventually Anna says, “I know everything about you. And I still love you.” These lines arrive at an interesting point in the narrative. For while Season 4 opened with the perennial question, “Who is Don Draper?,” the truth is that we viewers, like Anna, know everything there is to know about Don. And we have continued to watch him—if not quite to love him. But it is getting harder: and, quite frankly, Episode 3 was not good news.

I do not mean simply that the news is not good for Don, though it clearly is not. For years we have watched him in the long free fall depicted in the opening credits. In the last two weeks we have seen him hit bottom. As a married man, with a beautiful wife and family to anchor him, Don was a figure of dizzying disencumbrance: a Madison Avenue flâneur. As a divorcé living alone in Greenwich Village, he is drinking too much and relying on a small army of obliging women, from his housekeeper Celia, call girl Candace, and secretary Allison, to Phoebe, the young nurse who lives down the hall.

Now, by Episode 3, you might say (to paraphrase Oscar Wilde) that he is lying in the gutter, but not looking at the stars.

Of course, Don’s decline makes perfect narrative sense. The first two episodes are artistically compelling, no matter how disturbing (at times) to watch. In last week’s episode, as my colleague Rob Rushing wrote in his splendid post on Mad Men’s love affair with color, the storyline of a not-so-merry Christmas in 1964 is shot through with jolts of gorgeous design.

Rob’s thoughts on the tension between self-conscious aestheticism and realist narration—the object of which, as Henry James famously pronounced, is to “compete with life”—may prompt us to think about the various devices through which dramas like Mad Men invent televisual forms to do the work of omniscient narration. Through such conventions, serial television approximates the complexity of novels like James’s Portrait of a Lady (1881), or my own favorite Mad Men precursor, Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary (1856), both of which, much like today’s “quality television,” appeared serially before being published in volumes, like a boxed set of DVDs.

In Episode 2, Don’s one-night-stand with his secretary, a sad violation of his own professional ethic, is interrupted by the scene of Sally looking out her suburban window before she gets into bed. Is she still thinking of the Santa Claus whom she knows will not be home for Christmas this year (as in the letter Allison read to Don at the office)? Sally’s palpable loss inflects her father’s slide into alcoholic self-pity. Don has always been a selfish bastard and self-deceiver, but he has also had a perverse integrity that accounts for the many almost Nietzschean moments in which he transcends the surrounding void. And he has often been a tender father.

In Episode 2, Don’s one-night-stand with his secretary, a sad violation of his own professional ethic, is interrupted by the scene of Sally looking out her suburban window before she gets into bed. Is she still thinking of the Santa Claus whom she knows will not be home for Christmas this year (as in the letter Allison read to Don at the office)? Sally’s palpable loss inflects her father’s slide into alcoholic self-pity. Don has always been a selfish bastard and self-deceiver, but he has also had a perverse integrity that accounts for the many almost Nietzschean moments in which he transcends the surrounding void. And he has often been a tender father.Sally’s interpolation into the scene on the couch does not exonerate Don. But, like the work of a realist narrator, it puts the viewer in mind of the emotional situation subtending this sorry affair. Given Don’s capacity to push the past behind him, Allison and Sally will doubtless suffer longer for his misdeeds than he does. But he does suffer and—what is far more important—the confluence of these different notes of suffering “competes with life.”

The best episodes of Mad Men are like this: synchronic units embedded in a diachronic storyline. Through the magic of seriality, the richly layered “chapters” that compose each season, thematically unified by narrative care, stand alone artistically, even while contributing another piece to the puzzle. Typically each episode concludes with a song, chosen for periodicity as well as explanatory power.

Thus, Season 3, Episode 7 (“Seven Twenty Three”) closes with “Sixteen Tons,” including the classic line, “I owe my soul to the company store.” The song reflects on a storyline that finds Don forced to sign a contract with Sterling Cooper against his will. In the same episode, the besotted Don hallucinates an encounter with his dead father Archie, a flinty farmer who tells him a hillbilly joke and mocks his son’s upper-middle-class profession: “Look at your hands. They’re as soft as a woman’s. What do you do? What do you make? You grow bullshit.”

Another such episode is Season 2, Episode 12 (“The Mountain King”) which introduces Anna as the one person in Don’s life whom he trusts well enough to ask for advice. With Anna’s encouragement Don decides to return to Betty (from whom he has been estranged since she learned of the affair with Bobbie Barrett). The song this time, another country and western number called “Cup of Loneliness,” raises the possibility of redemption “from sin.”

We have not seen Anna since the “The Mountain King.” So when Don returns to her in the current episode, the title “Good News”—a literal translation of the Old English gospel—reminds us how elusive redemption has been for this pilgrim who grows bullshit for a living.

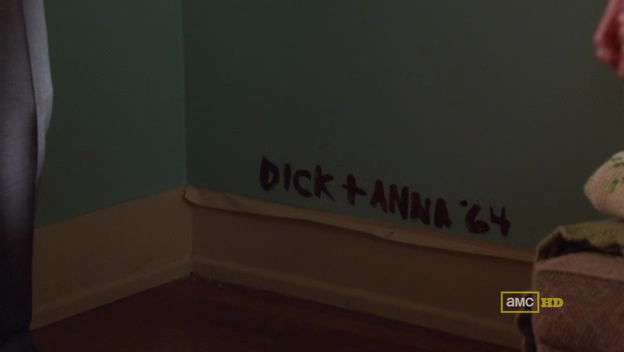

“Good News” ostensibly looks to Anna to facilitate another turning point in Don’s life. But her words of encouragement for the man she calls Dick—“I’m so damned proud of you”—are hopelessly out of touch. Under her nose he betrays her trust, trying to hit on her niece Stephanie whom he has known as a girl. Where Anna’s grasp on Don’s meditation in an emergency was strong in “The Mountain King,” this time around it’s her older sister who pins him down, rebuking this Dick for not keeping his pants on, and reminding him that he is powerless to save Anna from cancer.

Elsewhere in the episode “good news” takes the form of a “magnificent year” for the fledgling ad agency. And for Joan, the good news is that the two “procedures” she has undergone in the past should not prevent her from becoming pregnant. In an oddly ironic moment, her usually loathsome husband shows a competence we have not yet seen, regaling Joan with a hillbilly joke while tending her injured finger. (It is the same kind of joke Archie Whitman tells Don while mocking his woman’s hands—connecting Don and Dr. Harris for the first time since the latter raped his future wife in Don’s office.)

With the visit to Anna over, Don cancels his trip to Acapulco and spends New Years’ Eve on an airplane, drinking. When he returns to the office—always the place Don goes to collect himself—he finds Lane Pryce who has just learned that his wife has left him.

With the visit to Anna over, Don cancels his trip to Acapulco and spends New Years’ Eve on an airplane, drinking. When he returns to the office—always the place Don goes to collect himself—he finds Lane Pryce who has just learned that his wife has left him.I suspect some viewers enjoyed the ratpack-meets-Bill-and-Ted adventures that follow. Don and Lane get drunk at the movies and Lane shouts Japanese-sounding nonsense. Don and Lane drink some more at a restaurant and, with Don’s offer to find him a “lady friend” for the evening, Lane abandons his reserve, leaps up from his chair, and slaps “a big, Texas belt buckle” across his groin—the huge steak he lacks the appetite to eat. Later at a nightclub, a young stand-up comic mocks the pair—calling them “George and Martha”—until the arrival of their hired dates elicits a correction: “I guess I was wrong; you’re not queers, you're rich.”

As I have written before of Don, “Though superficially a ‘man’s man,’ he does not long for intimacy with other men.” He has only rarely taken part in male bonding rituals—and never at the office where he maintains fastidious distance from high jinks of any kind (recall his absence during the lawn mower debacle in the sublime Season 3 episode, “Guy Walks into an Ad Agency”). But just as he erred last week in prevailing upon a female employee for sexual gratification, so this week he ignored his advice to the departed Sal Romano: “Limit Your Exposure” (Season 3, Episode 1, “Out of Town”).

As I have written before of Don, “Though superficially a ‘man’s man,’ he does not long for intimacy with other men.” He has only rarely taken part in male bonding rituals—and never at the office where he maintains fastidious distance from high jinks of any kind (recall his absence during the lawn mower debacle in the sublime Season 3 episode, “Guy Walks into an Ad Agency”). But just as he erred last week in prevailing upon a female employee for sexual gratification, so this week he ignored his advice to the departed Sal Romano: “Limit Your Exposure” (Season 3, Episode 1, “Out of Town”).My point is not that Don should not make mistakes (when has he ever failed to make them?). Neither do I object to Don's having sex with prostitutes, and certainly not to his liking to be smacked around. Who would begrudge Don Draper the chance to indulge in erotic forms of contrition? Nor is the issue that Don and Lane should not console one another in their loneliness: we have seen Don and Roger in their cups like this before.

No, the bad news for me is the egregious artistic weakness of this episode as it follows these antics (yes, egregious, the word that Lane’s ex-secretary does not understand). “Good News” does not “compete with life” because, if truth be told, I do not believe it. Almost everything about this episode felt wrong to me: as though a script for Mad Men had been shopped out to the winner of a Banana Republic competition.

Consider the pathetic attempt to seduce Anna’s niece on her mother’s driveway because she is so “beautiful and young.” The Don of the past exerted more self-control; and unlike the credible one-night-stand with Allison, no circumstances were offered to explain such pure lechery. Yes, Don is broken, but he has not been body snatched. Why would he risk hurting Anna or driving a wedge between them for something so fleeting?

Even the music was off kilter: why bring “Old Cape Cod” to mind in an episode shot in Southern California? Better still, why conclude this episode with a television soundtrack instead of the usual period song? In fact, a good choice was already on hand in “The House of the Rising Sun,” briefly heard at the nightclub and admired by Janine—even though she doesn’t go to Barnard.

Although Bob Dylan recorded this song in 1961 it was the Newcastle rock group, the Animals, whose supremely soulful version of this ballad of a “poor boy” with “a gamblin’ man” father went to number one in 1964:

Oh mother tell your childrenNot to do what I have doneSpend your lives in sin and miseryIn the House of the Rising Sun.

It may seem like a quibble but the underuse of this song seems to me to perpetuate Mad Men's tin-eared relation to rock and roll, a subject it has noticeably--not to say egregiously--marginalized. It is as though the show--even as it ages Don, and presents him in the most abject light--is afraid to show us what a real rock star looked like in 1964: the kind who might appeal to Janine and Stephanie. In one of several scenes that fall flat for me, Don and Stephanie spar about politics and he tells her she can combat the "pollution" of advertising if she "stops buying things." The problem is, I don't believe either of them: not him when he tells her that she is in charge; not her when she tells him that she might stop buying.

It may seem like a quibble but the underuse of this song seems to me to perpetuate Mad Men's tin-eared relation to rock and roll, a subject it has noticeably--not to say egregiously--marginalized. It is as though the show--even as it ages Don, and presents him in the most abject light--is afraid to show us what a real rock star looked like in 1964: the kind who might appeal to Janine and Stephanie. In one of several scenes that fall flat for me, Don and Stephanie spar about politics and he tells her she can combat the "pollution" of advertising if she "stops buying things." The problem is, I don't believe either of them: not him when he tells her that she is in charge; not her when she tells him that she might stop buying.No, just this once it is me who stopped buying.

I have been watching this show with such unadulterated pleasure, I have become a kind of Conrad Hilton: tetchy and demanding.

Did you hear that Mr. Weiner? When I say I want the moon, I expect the moon.