[The next in our multi-authored series of posts on the fourth season of Mad Men, posted prior to the publication ofMAD WORLD: Sex, Politics, Style and the 1960sby Duke University Press, is by Michael Bérubé, Paterno Family Professor of English at Penn State (and honorary lifetime affiliate of the Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory]

[The next in our multi-authored series of posts on the fourth season of Mad Men, posted prior to the publication ofMAD WORLD: Sex, Politics, Style and the 1960sby Duke University Press, is by Michael Bérubé, Paterno Family Professor of English at Penn State (and honorary lifetime affiliate of the Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory]"PITCHING"

Written by Michael Bérubé (English, Penn State)

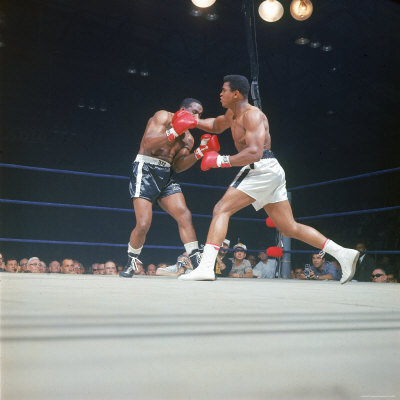

Well, that was an episode. Peggy breaks down and cries. Don breaks down and cries. Anna appears as a spirit with a suitcase. Peggy and Mark break up. Cooper has no balls. Duck drops his drawers, decks Don. And oh yes, Clay beats Liston. As Don says to Peggy, by way of explaining why he slept with Allison despite his “rules” about “work,” “people do things.” Where to start?

I’ll start where Sandy Camargo left us last week, with her post about the metatextuality of Mad Men. The Meta Mad Men were on full display in episode six (“Waldorf Stories”), of course, because of the Emmy/Clio awards and the Breyers ice cream ad. Episode seven, “The Suitcase,” is less extravagantly meta (though Hellmann’s Mayonnaise has picked up where Breyers left off), but perhaps makes the point all the more effectively: it’s all about the pitching, at every level.

The episode starts with the Samsonite team doing its pitch to Don; that failure is followed by Duck’s pitch to Peggy, which sounds enticing for a few seconds until Peggy realizes there’s nothing behind it but a drunk and a business card; Don declines Roger’s invitation to come out and get hammered (again), saying wryly, “that’s an attractive offer”; Peggy’s mother chides her for standing up Mark, “I don’t know how many nice boys you think are lining up for you.” Don and Peggy have it out over who deserves the credit for Glo-Coat. And later, at the diner, Peggy tells Don she’s just not interested in the pitch her world is offering her: "I know what I'm supposed to want," she says, "but it just never feels right, or as important as anything in that office." Fittingly, the episode is punctuated by scenes in which Peggy is about to leave the office—and decides not to. The only time she leaves, the episode actually gets more claustrophobic, as Peggy and Don talk about advertising and life in a series of tight shots in a diner and a bar.

The episode starts with the Samsonite team doing its pitch to Don; that failure is followed by Duck’s pitch to Peggy, which sounds enticing for a few seconds until Peggy realizes there’s nothing behind it but a drunk and a business card; Don declines Roger’s invitation to come out and get hammered (again), saying wryly, “that’s an attractive offer”; Peggy’s mother chides her for standing up Mark, “I don’t know how many nice boys you think are lining up for you.” Don and Peggy have it out over who deserves the credit for Glo-Coat. And later, at the diner, Peggy tells Don she’s just not interested in the pitch her world is offering her: "I know what I'm supposed to want," she says, "but it just never feels right, or as important as anything in that office." Fittingly, the episode is punctuated by scenes in which Peggy is about to leave the office—and decides not to. The only time she leaves, the episode actually gets more claustrophobic, as Peggy and Don talk about advertising and life in a series of tight shots in a diner and a bar. Duck really is a lousy ad man, by the way. The decision to court American Airlines was foolish—and you know very well Don’s never forgotten the Season 2 moment he had to tell Henry Wofford that Sterling Cooper would be dropping Mohawk Airlines. Here, Duck blows his pitch almost immediately, responding to Peggy’s perfectly reasonable question, “so what do you have so far?” by grousing, “I know it’s not a diamond necklace, but I did spend some money on those cards.” At which point Peggy knows more than enough to say (a) she appreciates the gesture and (b) does not take it seriously. Things go downhill from there, and then, at the end of the episode, right off a cliff.

Duck really is a lousy ad man, by the way. The decision to court American Airlines was foolish—and you know very well Don’s never forgotten the Season 2 moment he had to tell Henry Wofford that Sterling Cooper would be dropping Mohawk Airlines. Here, Duck blows his pitch almost immediately, responding to Peggy’s perfectly reasonable question, “so what do you have so far?” by grousing, “I know it’s not a diamond necklace, but I did spend some money on those cards.” At which point Peggy knows more than enough to say (a) she appreciates the gesture and (b) does not take it seriously. Things go downhill from there, and then, at the end of the episode, right off a cliff.But before we take the plunge, first let’s go back to “Waldorf Stories” for a moment, to the profoundly cringe-inducing pitch to the boys from Quaker Oats. Don’s impromptu taglines should be cited in academic committee meetings whenever people are flailing and just trying to make shit up on the fly (which is often): life ... the reason to get out of bed in the morning! Enjoy the rest of your life ... cereal! Yes, post-Clio Don is smashed, and his immediate reversion to Eager Don (the fur-selling Don we see in the flashbacks with Roger) is embarrassing. But the original “eat life by the bowlful” line, with the little kid and the big bowl and spoon, isn’t bad at all. Granted, it’s not nearly as good as the famous “Mikey Likes It,” and surely Weiner chose it for that reason: everyone and her brother associates Life with that ad, and rightly so. But if you compare the “bowlful” ad to what Life was actually doing back in the day, it’s frickin’ genius:

(Hat tip. Check out the 1967 ad, as well.) So I like the Life pitch. Kids will like the giant bowl of cereal. Moms will see it and get a twinge about how little their kid still is, even though they have to deal with life. Get those two together in a market and I think we’re gonna sell some cereal. Perhaps if Don weren’t so drunk, he could have worked the nostalgia angle the way he did for Kodak, masterfully, instead of burping and stumbling through it. But the idea itself is really pretty good. And the response from Quaker Oats? “It’s a little smart for regular folks.” The rejection recalls the Jantzen response (skin in a bikini ad, oh my!) and Conrad Hilton’s crazy-old-coot response to Don’s global-Hilton campaign (where’s the moon? I wanted the moon!). For anyone who has ever pitched a good idea to anyone, in any business (including academe? oh, absolutely), moments like these are infuriating. How much more infuriating it is that the slogan they like is the tired, predictable one Don stole from Danny. “A home run,” indeed. “That dog will hunt.” The meeting ends as a kind of class reunion of sales clichés, Don thinks he’s saved the day again, and off we go into the lost weekend. My point is not that I identified with Don for a moment, even as I cringed at his rapid-fire, erratic, weak-sauce slogan pitches; my point is that anyone who’s ever had a reasonably good idea shot down by “it’s a little smart for regular folks” should be identifying with Don at that moment. And much of the ambivalence of Mad Men toward its own metatextual success—that is, its own spectacular success at selling itself to us—depends on that dynamic. That’s not to say that everything MM does on this score is a success: notably, Ginia Bellafante wasn’t buying Jon Hamm’s performance in the flashbacks. “Hamm,” she wrote, “wore the same goofy, eager-beaver expression he did when we saw him as a car salesmen in the early ’50s a few seasons ago. He tries too hard to make the early Don seem like an ingratiating rube, so hard, in fact that the effect is to make Don’s eventual transition to a cool, everybody-comes-to-me, know-it-all seem utterly inconceivable.” Which is to say, in meta-speak, that Hamm tries too hard to show Don trying too hard. (I disagree; I think one of the points of the Life pitch is that Don’s subject-supposed-to-know facade can drop in a second. Such is Don’s ... life. But the point is that not everyone likes how Hamm handles Don’s self-presentation. Like that Mikey kid—he hates everything.)

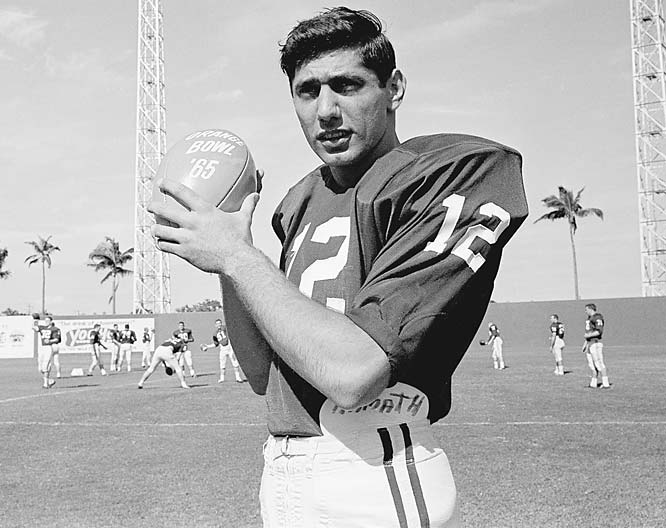

OK, now to Samsonite. This time, it’s Don who doesn’t go for the pitch, and though he’s nowhere near the level of cluelessness of the Quaker Oats boys, we see that yet again, Don doesn’t have the pop-culture chops he’s going to need for the second half of the ‘60s. “Endorsements are lazy,” Don says, “and I don’t like Joe Namath.” Sure, endorsements can be a cheap shortcut. But the “football” premise isn’t terrible -- arguably better than American Tourister’s “suitcase in a gorilla cage” campaign (1970, but alluded to here by way of the “elephant on a suitcase” suggestion), and light-years beyond Samsonite’s recent Cosmolite campaign. And who knows? Maybe that Namath kid will make a name for himself after all. But Don blows off the Namath idea, just moments after he’s plunked $100 down on Liston because Clay is a “loudmouth” who proclaims he’s the greatest and therefore can’t be. Don wasn’t so hot on that Kennedy kid, either; he was flat-out flummoxed by Doyle Dane Bernbach’s VW “Lemon” ads; and he doesn’t seem the least bit interested in the Fab Four. (DDB, btw, was also responsible for “Mikey likes it.”) So there’s your setup: the failed pitch is the premise for the entire episode, or, as Peggy puts it when Don tells her she doesn’t have to stay, “I do have to be here because of some stupid idea from Danny, who you had to hire because you stole his other stupid idea because you were drunk.” Moss’s delivery is brilliant (and the line follows another Peggy zinger, “it’s not my fault you don’t have a family or friends or anywhere else to go”). The stupid idea keeping them there? Samsonite is tough. But as Don notes at one point in the evening, every time we get down to working on it, we abandon the toughness idea. Indeed we do: the ideas are too obvious—football, elephants, throwing suitcases off buildings. “I can’t tell the difference anymore between something that’s good and something that’s awful,” Peggy confesses in the diner. “Well, they’re very close,” Don replies, anticipating Spinal Tap’s classic formulation, “there’s a fine line between stupid and clever.” “But the best idea always wins, and you know it when you see it.” Reassuring words—except that it doesn’t, and you don’t. Sometimes “the cure for the common breakfast” wins, because the clients are dolts. Or sometimes the creative director doesn’t like “Lemon.” Or, to take a contemporary example, sometimes the same agency that’s capable of producing the brilliant “aliens stole our moon rover’s tires while we were dancing to ‘Jump Around’” Bridgestone ad is also capable of producing the stupid and sexist “what if Mrs. Potato Head lost her mouth and had to stop yapping in the car” Bridgestone ad. You know, the one that played during the first commercial break in episode seven. Besides, the problem with “Samsonite is tough” (and, perhaps, the reason we keep abandoning it) is that it seems there’s something else lurking in the margins, something we don’t want to acknowledge. Like making that phone call to California. Or Uncle Mack’s line about how a man needs to keep a suitcase packed because he “needs to be ready to go any moment.” “Maybe it’s a metaphor,” Don murmurs. And when spectral Anna appears at the 3 AM of Don’s dark night of the soul, we get the point—yes, it’s a metaphor, all right, but surely we can’t build a pitch around Samsonite: Memento Mori. We learned in “Waldorf Stories” that life is “a scary word to anyone at any age.” Yes, well, just try death. That dog won’t hunt. Besides, who wants toughness, anyway? Duck Phillips is tough—why, he killed seventeen men in Okinawa, and here he is in a drunken rage, prepared to smash Don’s nose up into his brain. (Seventeen kills! Don’s Korean experience, not so impressive.) And what a ridiculous attempt at a punch that was! Good for Don for wanting to KO Duck for saying to Peggy, “I guess when screwing me couldn’t get you anything you had to go back to Draper” and calling her a whore. But not even Sonny Liston would have pretended to go down on a phantom punch as bad as Don’s. No, Don doesn’t do “tough” very well. He winds up on Peggy’s lap, barely able to get out one last slurred sentence, “sorry if I embarrassed you.” “Let’s go someplace darker,” Don said, quitting the diner. Well, they did.

OK, now to Samsonite. This time, it’s Don who doesn’t go for the pitch, and though he’s nowhere near the level of cluelessness of the Quaker Oats boys, we see that yet again, Don doesn’t have the pop-culture chops he’s going to need for the second half of the ‘60s. “Endorsements are lazy,” Don says, “and I don’t like Joe Namath.” Sure, endorsements can be a cheap shortcut. But the “football” premise isn’t terrible -- arguably better than American Tourister’s “suitcase in a gorilla cage” campaign (1970, but alluded to here by way of the “elephant on a suitcase” suggestion), and light-years beyond Samsonite’s recent Cosmolite campaign. And who knows? Maybe that Namath kid will make a name for himself after all. But Don blows off the Namath idea, just moments after he’s plunked $100 down on Liston because Clay is a “loudmouth” who proclaims he’s the greatest and therefore can’t be. Don wasn’t so hot on that Kennedy kid, either; he was flat-out flummoxed by Doyle Dane Bernbach’s VW “Lemon” ads; and he doesn’t seem the least bit interested in the Fab Four. (DDB, btw, was also responsible for “Mikey likes it.”) So there’s your setup: the failed pitch is the premise for the entire episode, or, as Peggy puts it when Don tells her she doesn’t have to stay, “I do have to be here because of some stupid idea from Danny, who you had to hire because you stole his other stupid idea because you were drunk.” Moss’s delivery is brilliant (and the line follows another Peggy zinger, “it’s not my fault you don’t have a family or friends or anywhere else to go”). The stupid idea keeping them there? Samsonite is tough. But as Don notes at one point in the evening, every time we get down to working on it, we abandon the toughness idea. Indeed we do: the ideas are too obvious—football, elephants, throwing suitcases off buildings. “I can’t tell the difference anymore between something that’s good and something that’s awful,” Peggy confesses in the diner. “Well, they’re very close,” Don replies, anticipating Spinal Tap’s classic formulation, “there’s a fine line between stupid and clever.” “But the best idea always wins, and you know it when you see it.” Reassuring words—except that it doesn’t, and you don’t. Sometimes “the cure for the common breakfast” wins, because the clients are dolts. Or sometimes the creative director doesn’t like “Lemon.” Or, to take a contemporary example, sometimes the same agency that’s capable of producing the brilliant “aliens stole our moon rover’s tires while we were dancing to ‘Jump Around’” Bridgestone ad is also capable of producing the stupid and sexist “what if Mrs. Potato Head lost her mouth and had to stop yapping in the car” Bridgestone ad. You know, the one that played during the first commercial break in episode seven. Besides, the problem with “Samsonite is tough” (and, perhaps, the reason we keep abandoning it) is that it seems there’s something else lurking in the margins, something we don’t want to acknowledge. Like making that phone call to California. Or Uncle Mack’s line about how a man needs to keep a suitcase packed because he “needs to be ready to go any moment.” “Maybe it’s a metaphor,” Don murmurs. And when spectral Anna appears at the 3 AM of Don’s dark night of the soul, we get the point—yes, it’s a metaphor, all right, but surely we can’t build a pitch around Samsonite: Memento Mori. We learned in “Waldorf Stories” that life is “a scary word to anyone at any age.” Yes, well, just try death. That dog won’t hunt. Besides, who wants toughness, anyway? Duck Phillips is tough—why, he killed seventeen men in Okinawa, and here he is in a drunken rage, prepared to smash Don’s nose up into his brain. (Seventeen kills! Don’s Korean experience, not so impressive.) And what a ridiculous attempt at a punch that was! Good for Don for wanting to KO Duck for saying to Peggy, “I guess when screwing me couldn’t get you anything you had to go back to Draper” and calling her a whore. But not even Sonny Liston would have pretended to go down on a phantom punch as bad as Don’s. No, Don doesn’t do “tough” very well. He winds up on Peggy’s lap, barely able to get out one last slurred sentence, “sorry if I embarrassed you.” “Let’s go someplace darker,” Don said, quitting the diner. Well, they did.  On the way to that tableau, the long evening reveals a striking number of Don-and-Peggy intimacies: Peggy speaks of how Mark doesn’t understand her; tells Don that her mother believes he is the father of her child (precisely because he was kind enough to visit her in the hospital); asks slyly about Allison; admits to grieving over her child; and, of course, acknowledges that she had an affair with Duck during a “confusing time.” Don, for his part, reveals that he’s a yokel from a farm, that his father was kicked to death by a horse (Peggy laughs, thinking he’s kidding), that he never knew his mother, and, breaking down, that he’s just lost the only person who knew him. “That’s not true,” Peggy replies, having come to know Don pretty well—except, of course, for the part about the war and Dick Whitman. (Speaking of which, am I crazy to be seeing in Don occasional allusions to Robert Crumb’s “Whiteman”?) But anytime you’re telling your boss that everyone thinks you slept with him to get the job, and that everyone thinks it’s funny, like the possibility is so remote ... well, that’s kind of intimate. As is trading stories of witnessing one’s father’s death. Echoing Don’s office-kitchen conversation with Faye in episode five, the Don-Peggy intimacies begin with a disavowal. Then, it was Don’s “why does everybody have to talk about everything?” followed by his admission that he doesn’t know how to be with (or without) his kids. Now, it’s this exchange:

On the way to that tableau, the long evening reveals a striking number of Don-and-Peggy intimacies: Peggy speaks of how Mark doesn’t understand her; tells Don that her mother believes he is the father of her child (precisely because he was kind enough to visit her in the hospital); asks slyly about Allison; admits to grieving over her child; and, of course, acknowledges that she had an affair with Duck during a “confusing time.” Don, for his part, reveals that he’s a yokel from a farm, that his father was kicked to death by a horse (Peggy laughs, thinking he’s kidding), that he never knew his mother, and, breaking down, that he’s just lost the only person who knew him. “That’s not true,” Peggy replies, having come to know Don pretty well—except, of course, for the part about the war and Dick Whitman. (Speaking of which, am I crazy to be seeing in Don occasional allusions to Robert Crumb’s “Whiteman”?) But anytime you’re telling your boss that everyone thinks you slept with him to get the job, and that everyone thinks it’s funny, like the possibility is so remote ... well, that’s kind of intimate. As is trading stories of witnessing one’s father’s death. Echoing Don’s office-kitchen conversation with Faye in episode five, the Don-Peggy intimacies begin with a disavowal. Then, it was Don’s “why does everybody have to talk about everything?” followed by his admission that he doesn’t know how to be with (or without) his kids. Now, it’s this exchange: Don: Stay and visit. Peggy: I’ve got nothing to say. Don: Sure you do. Peggy: No. It’s personal. Don: We have personal conversations. Peggy: No we don’t. And I think you like it that way. I know I do. Don: Suit yourself.Whereupon Peggy immediately opens up: “We’re supposed to be staring at each other over candlelight, and he invites my mother?” What a lousy offer that is: Mark’s pitch, like Duck’s, sucks. Note that until we get to “he,” it’s not entirely clear who “we” are.

But Don’s and Peggy’s will not be, must not be, a romantic intimacy. It’s not merely that Don has rules about work—rules he observes as he does all other rules, irregularly. It’s that the only way Don and Peggy can maintain the right workplace intimacy—holding hands as they gaze on the sketch of Samsonite-as-Ali looming over a defeated Tourister, mutely acknowledging all they have gone through on their way to producing this image—is by finding the right place for the “personal.” “Don’t get personal because you didn’t do your work,” Don snaps when Peggy reminds him that he stole Danny’s line because he was drunk. The personal, I might say, is not a pitch (except on a TV show where it is part of the pitch). And when we stop pitching for a moment, we can admit to ourselves that we still think about the child we gave away, or the children we miss and don’t know how to care for. But everything else is a pitch, which is why Mad Men seems so ambivalent about the success of its pitchers. Don’s degradation this year has been the subject of much discussion, and by now—with Roger sneaking off to a bar in the middle of dinner, complaining that the AA crowd is “self so righteous,” Don retching his guts into the toilet, and Duck trying to defecate in what he thinks is Don’s office—it almost appears as if Weiner and company are working overtime (perhaps staying in the office all night!) to make sure his clients don’t decide they like his product for the wrong reason. Is the show going over the top in its insistence that its leading men are hopeless alcoholics? Mad Men caught on in part because of its impeccable sense of style, because its promise to reveal How We Lived Then (and maybe How We Got Here), and because (as one Lauren Goodlad put it), the leading man is hot. Well, Jon Hamm is indeed hot, and when Draper becomes the sujet supposé savoir, he embodies a form of masculinity that remains extremely attractive to men and women alike.

But Don’s and Peggy’s will not be, must not be, a romantic intimacy. It’s not merely that Don has rules about work—rules he observes as he does all other rules, irregularly. It’s that the only way Don and Peggy can maintain the right workplace intimacy—holding hands as they gaze on the sketch of Samsonite-as-Ali looming over a defeated Tourister, mutely acknowledging all they have gone through on their way to producing this image—is by finding the right place for the “personal.” “Don’t get personal because you didn’t do your work,” Don snaps when Peggy reminds him that he stole Danny’s line because he was drunk. The personal, I might say, is not a pitch (except on a TV show where it is part of the pitch). And when we stop pitching for a moment, we can admit to ourselves that we still think about the child we gave away, or the children we miss and don’t know how to care for. But everything else is a pitch, which is why Mad Men seems so ambivalent about the success of its pitchers. Don’s degradation this year has been the subject of much discussion, and by now—with Roger sneaking off to a bar in the middle of dinner, complaining that the AA crowd is “self so righteous,” Don retching his guts into the toilet, and Duck trying to defecate in what he thinks is Don’s office—it almost appears as if Weiner and company are working overtime (perhaps staying in the office all night!) to make sure his clients don’t decide they like his product for the wrong reason. Is the show going over the top in its insistence that its leading men are hopeless alcoholics? Mad Men caught on in part because of its impeccable sense of style, because its promise to reveal How We Lived Then (and maybe How We Got Here), and because (as one Lauren Goodlad put it), the leading man is hot. Well, Jon Hamm is indeed hot, and when Draper becomes the sujet supposé savoir, he embodies a form of masculinity that remains extremely attractive to men and women alike.  But in season four, we’re getting a different pitch, one that puts Peggy at the center—a center from which we can see why that traditional form of masculinity isn’t worth aspiring to, and why the things Peggy is “supposed to want” will never feel right. Peggy has entered the door of the men’s room this time, and Don leaves his door open to her in the end. Will the pitch work? I’m sold, but then, I was sold on “eat life by the bowlful,” too. As long as one doesn’t regurgitate life by the bowlful as well. One final thing. Why is there a dog in the Parthenon? I don’t know. Why is there a mouse in Don’s office?

But in season four, we’re getting a different pitch, one that puts Peggy at the center—a center from which we can see why that traditional form of masculinity isn’t worth aspiring to, and why the things Peggy is “supposed to want” will never feel right. Peggy has entered the door of the men’s room this time, and Don leaves his door open to her in the end. Will the pitch work? I’m sold, but then, I was sold on “eat life by the bowlful,” too. As long as one doesn’t regurgitate life by the bowlful as well. One final thing. Why is there a dog in the Parthenon? I don’t know. Why is there a mouse in Don’s office?