[The next in our multi-authored series of posts on the fourth season of Mad Men, posted prior to the publication of MAD WORLD: Sex, Politics, Style and the 1960s by Duke University Press, is by Adam Kotsko, visiting professor of Religion at Kalamazoo College and author of a forthcoming book, Awkwardness. Kotsko is also a blogger at An und fur sich]

[The next in our multi-authored series of posts on the fourth season of Mad Men, posted prior to the publication of MAD WORLD: Sex, Politics, Style and the 1960s by Duke University Press, is by Adam Kotsko, visiting professor of Religion at Kalamazoo College and author of a forthcoming book, Awkwardness. Kotsko is also a blogger at An und fur sich]"THE HAIL MARY PASS"

Written by Adam Kotsko (Kalamazoo College)

I was jealous that I wasn’t the one to write on the last episode, which was arguably one of the best of the series. Even more, though, I was worried about writing on the episode immediately after one of Don’s epiphanies, because the writers have a habit of making Don backslide as quickly as possible. Thankfully, they avoided that signature gesture this time, with a result that was low-key but satisfying.

Coming off an episode that focused on the relationship between Don and Peggy, the writers maintain that focus, organizing the narrative around parallel plots involving each of them. The two only come back together when Peggy decides to take care of the raucous boys—a group so obnoxious that it strained credulity to think that anyone would act like that at work—and Don advises her that she’ll be better off if she resolves the problem herself.

Alan Sepinwall claims that Joan’s response to Peggy shows that Don’s advice was wrong, but I would argue instead that it shows the intrinsically impossible position Peggy is in, the dynamic where asserting greater authority in the male context only alienates her further from women. She could perhaps choose a more “feminine” mode of authority, but when her primary examples are that are Bobbie Barrett and the tragically diminished Joan, one can hardly blame her for taking Don’s advice.

In the rest of this post, however, I would like to focus on Don’s storyline, which is the episode’s real emotional center of gravity. Throughout this season, which to me has often felt scattered and disappointing, I have been thinking back on season two. Watching it one episode at a time, I was just as dissatisfied, but when I rewatched it in a couple days in preparation for Season 3, everything seemed to fall together. I wrote an article in the wake of that experience, arguing that the writers cycle through a variety of ways for Don to approach his identity. Having saved his identity as Don Draper from the threats posed by his brother and Pete, Don does everything he can to ensure that no similar crisis can happen again. Yet as Don tries and fails to control his personal brand, his life slowly falls apart, leading him to return to the zero-point of his current identity: the home of Anna Draper, who knows him as Dick Whitman and graciously gives him permission to use the identity he stole. In a symbolic baptism scene, he accepts the gift of Don Draper’s identity and returns home to find a variety of other gifts: a half million dollars, a legal loophole that allows him to maintain his creative integrity and humiliate his rival Duck, and an unexpected pregnancy that brings Betty back to his arms.

In the rest of this post, however, I would like to focus on Don’s storyline, which is the episode’s real emotional center of gravity. Throughout this season, which to me has often felt scattered and disappointing, I have been thinking back on season two. Watching it one episode at a time, I was just as dissatisfied, but when I rewatched it in a couple days in preparation for Season 3, everything seemed to fall together. I wrote an article in the wake of that experience, arguing that the writers cycle through a variety of ways for Don to approach his identity. Having saved his identity as Don Draper from the threats posed by his brother and Pete, Don does everything he can to ensure that no similar crisis can happen again. Yet as Don tries and fails to control his personal brand, his life slowly falls apart, leading him to return to the zero-point of his current identity: the home of Anna Draper, who knows him as Dick Whitman and graciously gives him permission to use the identity he stole. In a symbolic baptism scene, he accepts the gift of Don Draper’s identity and returns home to find a variety of other gifts: a half million dollars, a legal loophole that allows him to maintain his creative integrity and humiliate his rival Duck, and an unexpected pregnancy that brings Betty back to his arms.

If Season 2 portrays the breakdown of Don’s strategy of trying to unilaterally control his identity, Season 3 undercuts the newfound strategy of receiving everything as a gift. His serendipitous relationship with Conrad Hilton blows up in his face, as does his devastating self-revelation to Betty. The season concludes with one of those inspired Hail Mary passes that define Don’s sociopathic genius—just as he seized control of his destiny by stealing Don Draper’s dog tags and accepting symbolic death, here he steals the Sterling Cooper identity from the British firm that is about to sell them, and condemn him to creative stagnation.

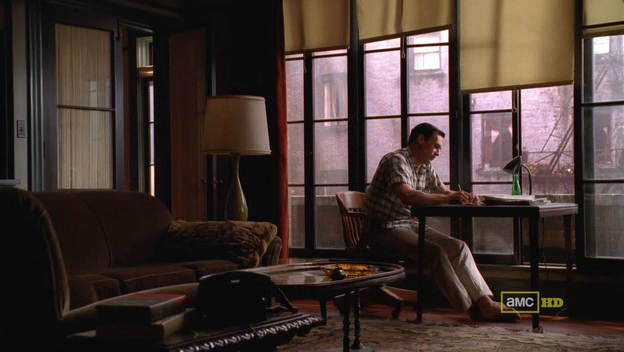

That season finale was one of the most invigorating episodes of the series, and in the wake of that, the first half of this season has felt like a gratuitous evacuation of everything appealing about Don. Instead of a suave seducer, Don became a pathetic drunk living in a dark apartment, hiring a prostitute to punish him for his transgressions. In fact, he became embarrassing to watch, with his inept attempts to pick up women, his violation of seemingly his only moral principle (don’t sleep with the secretary!), and his needy attempt to come up with a slogan for Life Cereal off the top of his head. When it’s revealed that Anna, his sole emotional anchor, has cancer, it seems clear that he is somehow going to find a way to go even further downhill—yet exactly the opposite happens. Why?

That season finale was one of the most invigorating episodes of the series, and in the wake of that, the first half of this season has felt like a gratuitous evacuation of everything appealing about Don. Instead of a suave seducer, Don became a pathetic drunk living in a dark apartment, hiring a prostitute to punish him for his transgressions. In fact, he became embarrassing to watch, with his inept attempts to pick up women, his violation of seemingly his only moral principle (don’t sleep with the secretary!), and his needy attempt to come up with a slogan for Life Cereal off the top of his head. When it’s revealed that Anna, his sole emotional anchor, has cancer, it seems clear that he is somehow going to find a way to go even further downhill—yet exactly the opposite happens. Why?

I think that the key is found in the swimming pool. Many have pointed out the apparent parallel to John Cheever’s short story “The Swimmer”; I believe that the real reference for the swimming pool is actually the aforementioned baptism scene from Season 2 ("The Mountain King"). The contrast is between letting the waves wash over him and fighting his own way through the water. The waves, we could say, are Anna’s love—as she says in Episode 3 ("Good News"), “I know everything about you, and I still love you.” Taking the two halves of that sentence, we could say that, based on last week's episode, "The Suitcase," Peggy represents the person who doesn’t know everything about him and still loves him—and the person who knows everything about him and doesn’t love him is Don himself. Anna doesn’t just love Don, she loves Don for Don (or, rather, Dick for Dick), taking the place of Don’s own self-love. In exchange, Don takes care of her, just as he doesn’t take care of himself.

I think that the key is found in the swimming pool. Many have pointed out the apparent parallel to John Cheever’s short story “The Swimmer”; I believe that the real reference for the swimming pool is actually the aforementioned baptism scene from Season 2 ("The Mountain King"). The contrast is between letting the waves wash over him and fighting his own way through the water. The waves, we could say, are Anna’s love—as she says in Episode 3 ("Good News"), “I know everything about you, and I still love you.” Taking the two halves of that sentence, we could say that, based on last week's episode, "The Suitcase," Peggy represents the person who doesn’t know everything about him and still loves him—and the person who knows everything about him and doesn’t love him is Don himself. Anna doesn’t just love Don, she loves Don for Don (or, rather, Dick for Dick), taking the place of Don’s own self-love. In exchange, Don takes care of her, just as he doesn’t take care of himself.

The reason Don’s bold gesture at the end of Season 3 doesn’t finally work, might be best summed up by paraphrasing a famous quote from former Iraqi Information Minister Muhammed Saeed al-Sahaf: “Don doesn’t control his destiny, he doesn’t even control himself.” Don can’t control his public image unless he can gain some kind of control over his internal life. Viewers might see Don’s moments of weakness as a humanizing gesture, but it’s important to attend to the content of those self-revelations. His moments of letting the mask down consistently reveal little other than self-pity, defensiveness, and panic—and his loss of control over his life and subsequent loss of control of his drinking have allowed all that to bubble up to the surface. The loss of his last life-preserver, Anna, could easily have resulted in him drowning, but instead he decided to learn to swim. In what might a bit of a stretch, we could say that just as he takes over the real Don Draper’s life when the latter dies, so he takes over Anna’s role of loving him when she dies.

This reversal is less striking than his two dramatic acts of identity theft and the end of Seasons 2 and 3 respectively, but it is arguably more extreme: for a man who has built an entire life out of a string of lucky breaks, and two or three moments of genuine inspiration, a turn toward introspection and self-control may be the greatest Hail Mary pass of them all.

In the rest of this post, however, I would like to focus on Don’s storyline, which is the episode’s real emotional center of gravity. Throughout this season, which to me has often felt scattered and disappointing, I have been thinking back on season two. Watching it one episode at a time, I was just as dissatisfied, but when I rewatched it in a couple days in preparation for Season 3, everything seemed to fall together. I wrote an article in the wake of that experience, arguing that the writers cycle through a variety of ways for Don to approach his identity. Having saved his identity as Don Draper from the threats posed by his brother and Pete, Don does everything he can to ensure that no similar crisis can happen again. Yet as Don tries and fails to control his personal brand, his life slowly falls apart, leading him to return to the zero-point of his current identity: the home of Anna Draper, who knows him as Dick Whitman and graciously gives him permission to use the identity he stole. In a symbolic baptism scene, he accepts the gift of Don Draper’s identity and returns home to find a variety of other gifts: a half million dollars, a legal loophole that allows him to maintain his creative integrity and humiliate his rival Duck, and an unexpected pregnancy that brings Betty back to his arms.

In the rest of this post, however, I would like to focus on Don’s storyline, which is the episode’s real emotional center of gravity. Throughout this season, which to me has often felt scattered and disappointing, I have been thinking back on season two. Watching it one episode at a time, I was just as dissatisfied, but when I rewatched it in a couple days in preparation for Season 3, everything seemed to fall together. I wrote an article in the wake of that experience, arguing that the writers cycle through a variety of ways for Don to approach his identity. Having saved his identity as Don Draper from the threats posed by his brother and Pete, Don does everything he can to ensure that no similar crisis can happen again. Yet as Don tries and fails to control his personal brand, his life slowly falls apart, leading him to return to the zero-point of his current identity: the home of Anna Draper, who knows him as Dick Whitman and graciously gives him permission to use the identity he stole. In a symbolic baptism scene, he accepts the gift of Don Draper’s identity and returns home to find a variety of other gifts: a half million dollars, a legal loophole that allows him to maintain his creative integrity and humiliate his rival Duck, and an unexpected pregnancy that brings Betty back to his arms.If Season 2 portrays the breakdown of Don’s strategy of trying to unilaterally control his identity, Season 3 undercuts the newfound strategy of receiving everything as a gift. His serendipitous relationship with Conrad Hilton blows up in his face, as does his devastating self-revelation to Betty. The season concludes with one of those inspired Hail Mary passes that define Don’s sociopathic genius—just as he seized control of his destiny by stealing Don Draper’s dog tags and accepting symbolic death, here he steals the Sterling Cooper identity from the British firm that is about to sell them, and condemn him to creative stagnation.

That season finale was one of the most invigorating episodes of the series, and in the wake of that, the first half of this season has felt like a gratuitous evacuation of everything appealing about Don. Instead of a suave seducer, Don became a pathetic drunk living in a dark apartment, hiring a prostitute to punish him for his transgressions. In fact, he became embarrassing to watch, with his inept attempts to pick up women, his violation of seemingly his only moral principle (don’t sleep with the secretary!), and his needy attempt to come up with a slogan for Life Cereal off the top of his head. When it’s revealed that Anna, his sole emotional anchor, has cancer, it seems clear that he is somehow going to find a way to go even further downhill—yet exactly the opposite happens. Why?

That season finale was one of the most invigorating episodes of the series, and in the wake of that, the first half of this season has felt like a gratuitous evacuation of everything appealing about Don. Instead of a suave seducer, Don became a pathetic drunk living in a dark apartment, hiring a prostitute to punish him for his transgressions. In fact, he became embarrassing to watch, with his inept attempts to pick up women, his violation of seemingly his only moral principle (don’t sleep with the secretary!), and his needy attempt to come up with a slogan for Life Cereal off the top of his head. When it’s revealed that Anna, his sole emotional anchor, has cancer, it seems clear that he is somehow going to find a way to go even further downhill—yet exactly the opposite happens. Why? I think that the key is found in the swimming pool. Many have pointed out the apparent parallel to John Cheever’s short story “The Swimmer”; I believe that the real reference for the swimming pool is actually the aforementioned baptism scene from Season 2 ("The Mountain King"). The contrast is between letting the waves wash over him and fighting his own way through the water. The waves, we could say, are Anna’s love—as she says in Episode 3 ("Good News"), “I know everything about you, and I still love you.” Taking the two halves of that sentence, we could say that, based on last week's episode, "The Suitcase," Peggy represents the person who doesn’t know everything about him and still loves him—and the person who knows everything about him and doesn’t love him is Don himself. Anna doesn’t just love Don, she loves Don for Don (or, rather, Dick for Dick), taking the place of Don’s own self-love. In exchange, Don takes care of her, just as he doesn’t take care of himself.

I think that the key is found in the swimming pool. Many have pointed out the apparent parallel to John Cheever’s short story “The Swimmer”; I believe that the real reference for the swimming pool is actually the aforementioned baptism scene from Season 2 ("The Mountain King"). The contrast is between letting the waves wash over him and fighting his own way through the water. The waves, we could say, are Anna’s love—as she says in Episode 3 ("Good News"), “I know everything about you, and I still love you.” Taking the two halves of that sentence, we could say that, based on last week's episode, "The Suitcase," Peggy represents the person who doesn’t know everything about him and still loves him—and the person who knows everything about him and doesn’t love him is Don himself. Anna doesn’t just love Don, she loves Don for Don (or, rather, Dick for Dick), taking the place of Don’s own self-love. In exchange, Don takes care of her, just as he doesn’t take care of himself.The reason Don’s bold gesture at the end of Season 3 doesn’t finally work, might be best summed up by paraphrasing a famous quote from former Iraqi Information Minister Muhammed Saeed al-Sahaf: “Don doesn’t control his destiny, he doesn’t even control himself.” Don can’t control his public image unless he can gain some kind of control over his internal life. Viewers might see Don’s moments of weakness as a humanizing gesture, but it’s important to attend to the content of those self-revelations. His moments of letting the mask down consistently reveal little other than self-pity, defensiveness, and panic—and his loss of control over his life and subsequent loss of control of his drinking have allowed all that to bubble up to the surface. The loss of his last life-preserver, Anna, could easily have resulted in him drowning, but instead he decided to learn to swim. In what might a bit of a stretch, we could say that just as he takes over the real Don Draper’s life when the latter dies, so he takes over Anna’s role of loving him when she dies.

This reversal is less striking than his two dramatic acts of identity theft and the end of Seasons 2 and 3 respectively, but it is arguably more extreme: for a man who has built an entire life out of a string of lucky breaks, and two or three moments of genuine inspiration, a turn toward introspection and self-control may be the greatest Hail Mary pass of them all.