[The next in our multi-authored series of posts on the fourth season of Mad Men, posted prior to the publication of MAD WORLD: Sex, Politics, Style and the 1960s by Duke University Press, is by Konstantine Klioutchkine, Associate Professor of German and Russian at Pomona College, and Sanja Lacan, PhD Candidate in Slavic Studies at UCLA]

[The next in our multi-authored series of posts on the fourth season of Mad Men, posted prior to the publication of MAD WORLD: Sex, Politics, Style and the 1960s by Duke University Press, is by Konstantine Klioutchkine, Associate Professor of German and Russian at Pomona College, and Sanja Lacan, PhD Candidate in Slavic Studies at UCLA]"ON FEELING, FILLING, AND FLYING"

Written by Konstantine Klioutchkine (German and Russian, Pomona College) and Sanja Lacan (Slavic Studies, UCLA)

“Fillmore Auto Parts: For the Mechanic in Every Man!” is the advertising slogan Dr. Faye Miller conjures up for three Fillmore executives in a meeting at the center of this season’s ninth episode, devoted, as its title suggests, to “Beautiful Girls.” Mad Men frequently structures its episodes around the language of advertising pitches, one of the most memorable of which is the well-known Kodak Carousel presentation at the end of Season 1 which Michael Berube discussed two weeks ago. Indeed, wordplay, including the kind found in many advertising campaigns, organizes the fabric of meaning in the show.

The wordplay in “Fillmore” evokes Don’s advice to Peggy from the Season 2 premier ("For Those Who Think Young") that she feel more in order to produce effective advertising—and also, perhaps, to produce an effective self. “You are the product,” he tells her, “you feeling something—that’s what sells.” Up to the current episode, the show’s fourth season has been purveying more feelings than fillings, a trajectory palpable in the portrayal of Don’s gradual descent into alcoholic despair until his rebirth in last week's episode ("The Summer Man"), as a person who, as Don says self-consciously, “sounds like a little girl, writing down what happened today” in a diary. “The Beautiful Girls” departs from this trend with an encouragement to turn from feeling to filling, from emotion to sex, from emasculation to the rediscovery of the mechanic in every man.

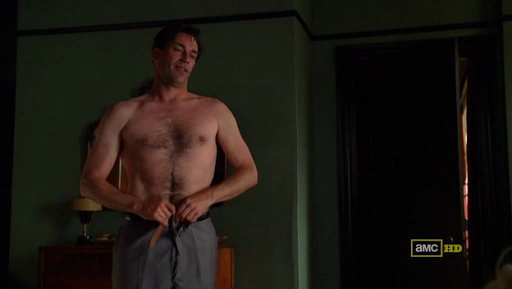

Fittingly, the episode’s opening scene of Don on the phone quickly cuts to a sex scene between Don and Faye, punctuated by a play on the transparent sexual implication of Don’s actual first name, Dick. As the characters are having sex they dislodge a lamp, prompting a suggestive question as to what might have broken: the lamp or Don’s phallus. The upshot of this wordplay is the celebration of Don’s post-swimming virility. But the return of Don’s manhood means more than mere sexual prowess: it is also related to the return of his ability to destroy human life. As far back as the award-winning pilot, “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” Don’s bohemian lover Midge describes him as a person capable of “leading sheep to slaughter.” In the current episode, Don’s potential for violence emerges in Ken Cosgrove’s jest that “Don Draper” be identified as the cause of death of his secretary, Miss Blankenship, in the coroner’s report.

Fittingly, the episode’s opening scene of Don on the phone quickly cuts to a sex scene between Don and Faye, punctuated by a play on the transparent sexual implication of Don’s actual first name, Dick. As the characters are having sex they dislodge a lamp, prompting a suggestive question as to what might have broken: the lamp or Don’s phallus. The upshot of this wordplay is the celebration of Don’s post-swimming virility. But the return of Don’s manhood means more than mere sexual prowess: it is also related to the return of his ability to destroy human life. As far back as the award-winning pilot, “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” Don’s bohemian lover Midge describes him as a person capable of “leading sheep to slaughter.” In the current episode, Don’s potential for violence emerges in Ken Cosgrove’s jest that “Don Draper” be identified as the cause of death of his secretary, Miss Blankenship, in the coroner’s report.Following the exchange about the (un)broken object, the dialogue between Don and Faye seems to take its cue from Tristram Shandy as they wonder about the time. Unlike in Lawrence Sterne’s famous 1759 work, in which Tristram’s conception is interrupted when his mother asks his father if he has remembered to wind the clock, no reproductive clock is being wound up here (at least none that we know of). Instead, the clock reminds the characters of the need to return to work. Ultimately, attitudes toward reproduction vis-à-vis the production of labor become an especially poignant matter in the episode which builds this motif in part out of sexual wordplay.

Another important scene concerned with filling involves Roger Sterling and Joan Harris walking down a lonely street after dinner. They fall victim to a hold-up and turn over an array of vaginal symbols--rings and a purse prominent among them--to the gun-brandishing assailant. After the latter leaves without taking a shot, Joan encourages Roger to make use of his own firing power, and they have sex in the street.

Extending this theme of shooting at women, the post-mugging coitus links with an earlier conversation between Peggy and her potential love interest, the politically-minded bohemian Abe. In response to Peggy’s comparison of her own struggles to those of African Americans, Abe points out that “they’re not shooting women to keep them from voting.” Peggy perceives Abe's insistence that she adopt his radical political views as a figurative shooting down of women. Sensitive to Abe’s penchant for aggressive proselytizing, Peggy’s lesbian friend Joyce extends the episode’s sexual banter by saying that Abe “pulled a boner.”

This comment leads to an exchange between Joyce and Peggy which amplifies the episode's sexually-charged wordplay. Joyce discusses male and female roles by constructing the metaphors of a masculine “vegetable soup” as a filler that requires a feminine “pot” to “heat ‘em up and hold ‘em.” Peggy, however, is not ready to agree. Before leaving, Joyce highlights Peggy’s symbolic masculinity by calling her “Peg.” This shortened version of the name Margaret evokes the idiom of “a square peg in a round hole,” reminding us that Peggy’s achievements and problems alike are inseparable from her resistance to stereotypical female roles.

How does this focus on sexual wordplay relate to the titular theme of the episode, “The Beautiful Girls”? The answer might lie in another set of wordplay that organizes the theme of women around images of birds. While working on a crossword puzzle, Bert Cooper asks his former secretary Miss Blankenship for help finding a three-letter word for a flightless bird. By naming the extinct emu, she both predicts her own demise and introduces avian wordplay into the episode, with the near homonym of emu and emo. Miss Blankenship might insist that she knows more about crossword puzzles than her ex-flame and ex-boss Bert Cooper, but she is no flightless bird. In Episode 7 (“The Suitcase”) Roger describes her as “a queen of perversions,” and in the current episode Bert compares her to an astronaut who ascended from her birth in a late-nineteenth-century barn, to her death on the 37th floor of a modern skyscraper.

The episode’s central figure of flight is Don’s daughter Sally, who flees her mother in order to play a Lolita-cum-wife to her father. But Sally’s flight also finds its limit when she falls to the floor before being forcibly returned to the care of her mother. This particular flight, couched as it is in various forms of intensely emotional behavior, may seem rather contrived, at least insofar as Sally models herself on the amateur detective Nancy Drew, whose book she reads while waiting in Don’s office. The ambivalence and uncertain agency expressed by Sally’s behavior may prove central to understanding the show’s depiction of the female condition. Limited by various social, economic, and cultural forces, many of them, nonetheless, prove highly capable of gaining some power over their circumstances.

The episode’s central figure of flight is Don’s daughter Sally, who flees her mother in order to play a Lolita-cum-wife to her father. But Sally’s flight also finds its limit when she falls to the floor before being forcibly returned to the care of her mother. This particular flight, couched as it is in various forms of intensely emotional behavior, may seem rather contrived, at least insofar as Sally models herself on the amateur detective Nancy Drew, whose book she reads while waiting in Don’s office. The ambivalence and uncertain agency expressed by Sally’s behavior may prove central to understanding the show’s depiction of the female condition. Limited by various social, economic, and cultural forces, many of them, nonetheless, prove highly capable of gaining some power over their circumstances.Two contrasting instances of wordplay clarify the logic of the bird theme, which became prominent in the first season, in Don’s repeated address to his wife Betty as “Birdie” and then in the 9th episode (“Shoot”) in which she took a BB gun at her neighbor’s doves to unleash her pent-up aggression at this symbol of her own lost freedom. Miss Blankenship complains that Faye always “breezes by,” singling her out as especially free: will she remain so now that she has succumbed to Don’s charms?

By contrast, the three-letter word for a flightless bird materializes at the end of the episode in the image of two figurative hens in Don’s office: his ex-wife Betty and his daughter Sally (their flower-patterned dresses distinguishing them from the more formally-dressed professional women). Their status as flightless is emphasized by the visual opposition in the scene in which Betty and Sally stand on one side of the reception area while the childless working women (supposedly freer? or flightier?) observe them from the other.

By contrast, the three-letter word for a flightless bird materializes at the end of the episode in the image of two figurative hens in Don’s office: his ex-wife Betty and his daughter Sally (their flower-patterned dresses distinguishing them from the more formally-dressed professional women). Their status as flightless is emphasized by the visual opposition in the scene in which Betty and Sally stand on one side of the reception area while the childless working women (supposedly freer? or flightier?) observe them from the other.By way of bringing together these two sets of wordplay, we suggest that the show puts a special emphasis on investigating the human condition of its characters through its symbolization of their attitudes to sexual practices. In this episode, the death of “the queen of perversions,” provides a signal to renew sexual endeavor, both corporeal and symbolic: Joan and Roger’s public sex, Faye and Don's sex, the forms of masturbation and oral sex which previous Season 4 episodes have depicted, and—per the episode’s preview—Peggy’s “receiving a romantic gift that could compromise her career.”

Although the theme of sexuality in “The Beautiful Girls” is organized around the male-centered slogan for Fillmore Auto Parts, the question about what forms sexuality should take is posed primarily to women, who are portrayed as erotically more creative and adventurous than men. Joyce might be right in her insistence that women are about to give up being pots in order to become vegetable soup in their own right.

The final scene of the episode, however, suggests that women’s options remain ambivalent and confusing. Joyce, Faye, and Joan do not get to determine which of the several elevator doors will open first and each fails to guess the one that will. They are momentarily confused before filling what becomes available. In the closing scene, Peggy arrives to the lobby in time to join Faye and Joan in the already open elevator car. She comes closest to making her own choice, but her choice is to join the two confused older women.

The final scene of the episode, however, suggests that women’s options remain ambivalent and confusing. Joyce, Faye, and Joan do not get to determine which of the several elevator doors will open first and each fails to guess the one that will. They are momentarily confused before filling what becomes available. In the closing scene, Peggy arrives to the lobby in time to join Faye and Joan in the already open elevator car. She comes closest to making her own choice, but her choice is to join the two confused older women.In this way she remains a square peg in a round hole, as the smile on her face contrasts with the visible distress of her colleagues. Ultimately, it appears that filling--as much fun, verbal and otherwise, as it might be--may be as fully disorienting as feeling. What will that portend for the option of flying?