[The first in the Unit for Criticism's multi-authored series of posts on Season 5 of AMC's Mad Men, prior to the publication of MAD MEN, MAD WORLD: Sex, Politics, Style, and the 1960s (Duke University Press) Eds. Lauren M. E. Goodlad, Lilya Kaganovsky and Robert A. Rushing

"Things Aren't Perfect"

Written by Lilya Kaganovsky (Slavic/Comparative Literature/Media & Cinema Studies)

Mad Men is growing old. I don’t mean that as a criticism;I mean that the show, without being a Bildungsroman (since no one ever grows wiser here, only older), is fundamentally about what it means to be an adult. Don has turned forty. Sally’s voice has dropped an octave. Joan has had a baby. Pete lives in the suburbs. Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce has entered a period of “stability” (“stable,” as Pete tells us, is that “step backwards between successful and failing”).

Even the ads for Miller 64 aired during the premiere point us to a certain demographic: “brewed for the better you.” The ad opens with an alarm clock about to turn to 6:30am and a picture of someone’s five-year old daughter on the nightstand. We are then treated to a daily routine of working out (“We run a mile before breakfast” goes the song), eating healthy (“I had a salad for lunch”), and the promise, that after a day of “balance” to have a Miller 64 with dinner because, “I’ve worked off my paunch.” Like the Heinz baked beans campaign pitched by Peggy in this episode, which imagines a “bean ballet” set to classical music and strikes the clients as old-fashioned, the Miller 64 ad is not targeted at the young “college” crowd, but at the many Mad Men viewers who, like Don, are turning forty. (“When you’re forty, how old will I be?” Don asks his son Bobby. “You'll be dead,” replies Bobby.) For his fortieth birthday, Harry gives Don a cane and Megan calls him an old man. As Betty tells Don in the Season 4 finale line repeated in the teaser that preceded Season 5’s two-hour premiere, “Things aren’t perfect.”

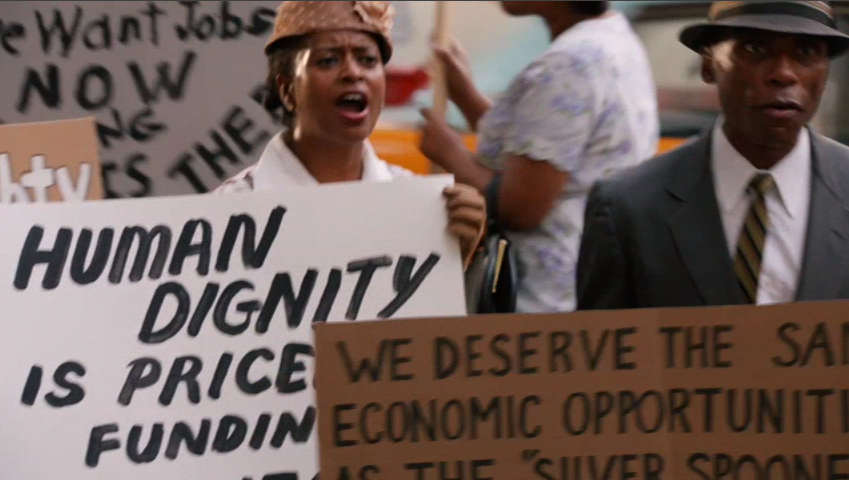

Season 5 opens with a picket line. Initial close ups of white police officers and passersby are quickly replaced by medium shots of black women and men carrying signs demanding work. This is the Civil Rights Movement, but it is also Occupy Wall Street, with these protests meant to reflect not only on our past, but also on our most recent historical moment. Our next series of shots takes us inside an office, which we immediately recognize as the part of an ad agency, even though we don’t know any of the four men working there: we suspect (and we will be proved wrong) that we are looking at the new Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce “creative” team — their obvious youth speaking to the next generation of Mad Men. Instead, the agency is Y&R: Young & Rubicam and, living up to their agency’s name, they react to the protests with an appropriate degree of childishness: annoyed by the noise coming from the street, they decide to “cool off” the protesters by first pouring and then throwing bags of ice water out the window. (There is an entire discourse of paper bags, barf bags, and body bags that runs through the episode.)

The opening sequence speaks to a series of changes that have taken places since we last saw our favorite characters seven months earlier (seven months by the show’s clock, seventeen months by ours). Trudy and Joan have both had their babies and each is looking a little worse for wear. As Pete Campbell puts it in his inimitable way, “there was a time when she wouldn’t leave the house in a robe.” Pete of course is speaking about Trudy, but his comment carries over to our first glimpse of Joan (preceded by a baby’s bottom and a hand applying diaper rash cream), still wearing a robe and pajamas in the middle of the afternoon. As her mother sarcastically notes, “You know you’re not exactly at your fighting weight.” (Joan begs to differ.)

Pete, meanwhile, has switched places with Don. An over-the-shoulder shot of Pete on the train is meant to remind us of our first glimpses of Don in Season 1: Pete has replaced Don on the commuter train moving between the city and its suburbs. While Don and Megan have moved into a gorgeous modern flat with a visible Manhattan skyline and audible traffic, Pete and Trudy have bought a house in the suburbs, and the shock of seeing their home for the first time is quite profound: nothing remains of the young modern couple with their well-appointed flat on the upper (upper) East side. Instead, Pete walks into what we first take to be the Drapers’ old kitchen, with the same kitchen cabinets and old-fashioned wallpaper. (To be clear, it is actually a different set, and we see a clear shot of a galley kitchen with a double sink on the right and a double stove on the left, as Pete despondently eats dry cereal out of a box — Trudy, it seems, has not yet mastered Betty’s homemaking skills.) The dingy-patterned wall paper, linoleum floor, and dark wood kitchen cabinets with their wrought-iron hinges no longer speak to the sense of bourgeois stability we first got from the Drapers’ home, before the cracks began to show. What might have passed for proper suburban upper-middle-class style five years earlier, now, in 1966, looks unbelievably shabby and depressing.

Pete, meanwhile, has switched places with Don. An over-the-shoulder shot of Pete on the train is meant to remind us of our first glimpses of Don in Season 1: Pete has replaced Don on the commuter train moving between the city and its suburbs. While Don and Megan have moved into a gorgeous modern flat with a visible Manhattan skyline and audible traffic, Pete and Trudy have bought a house in the suburbs, and the shock of seeing their home for the first time is quite profound: nothing remains of the young modern couple with their well-appointed flat on the upper (upper) East side. Instead, Pete walks into what we first take to be the Drapers’ old kitchen, with the same kitchen cabinets and old-fashioned wallpaper. (To be clear, it is actually a different set, and we see a clear shot of a galley kitchen with a double sink on the right and a double stove on the left, as Pete despondently eats dry cereal out of a box — Trudy, it seems, has not yet mastered Betty’s homemaking skills.) The dingy-patterned wall paper, linoleum floor, and dark wood kitchen cabinets with their wrought-iron hinges no longer speak to the sense of bourgeois stability we first got from the Drapers’ home, before the cracks began to show. What might have passed for proper suburban upper-middle-class style five years earlier, now, in 1966, looks unbelievably shabby and depressing.Style-wise, Season 5 does not disappoint: 1966 looks great, maybe even better than 1960 — skirts are shorter, heels are flatter, hair is longer. The colors, open space, and interior design that we first glimpsed in Palm Springs (Season 2, Episode 11, “The Jet Set”) are now part of the new Drapers’ new Manhattan home, and while we might miss Betty and her fainting couch, we know that Don has once again made the right move (“Marry early and often,” Ken Cosgrove’s wife jokes, looking at the plumper Jane Sterling.) But we also note those who are being left behind — not just Roger, who has no clients, no meetings, and has to share a secretary with Don, or Bert Cooper who waits patiently in the conference room for a meeting that’s taking place in the hallway, or Lane, who tries to seduce a young woman over the phone — but also Joan, Trudy, Jane, and even Peggy, whose clothes all speak to women aging out of the desirable twenty-something demographic. (We have yet to see Betty, of course, but I imagine that she, like Grace Kelly in Rear Window, always knows how to wear proper clothes.)

Mad Men has always been concerned with age because, unlike so much television, it is not a show about being young (it stars a leading man, for example, who even in his twenties always looked “mature”). And while we tend to associate the 1960s profoundly with youth, Mad Men wants us to see what it would have been like to live through it as adults — the “college kids” “sitting in” are not our focus. Instead, we are placed firmly inside the corporate world of bourgeois white conformism. As the Heinz client points out, speaking metaphorically for an entire generation, “beans” are not good by themselves, they are really better in a group.

Indeed, the Heinz baked beans ad campaign is one of the places we see this concern with age manifest itself. Peggy’s attempt to elevate the baked beans to the “art of supper” with new micro-photography and humor backfires, but the point is well taken: the desire to take something of humble origins to new heights. The clients wonder about the “message” — what will the viewer take away from the ad? Peggy’s claim is that it puts beans on your mind and shows you have a sense of humor, because beans are portrayed as far more important than they are. “Did you ever see beans up close?” asks the client, “They’re slimy… they look better in a group… beans is the war, the Depression, bomb shelters. We have to erase that.” “They have to be cool,” he continues, “I want kids in college… they have a hot plate, they’re sitting in… maybe it’s someone with a picket sign saying, 'We want beans!'”

A similar age gap manifests itself in Megan’s misguided desire to throw Don a surprise birthday party — she imagines that everyone loves birthdays (and surprises), while Don, as he puts it, hates to be the center of attention. That is of course not quite true: what Don hates is being the butt of a joke, which is precisely what he becomes. The title of the episode, “A Little Kiss,” is a translation of the French song Megan sings at Don’s surprise party, and it is of course not the first time that the show gives us a performance that reminds us that we are watching a spectacle. (Previous memorable sequences included Roger in blackface singing “My Old Kentucky Home,” Pete and Trudy dancing the Charleston, and Joan performing her own French song “C’est magnifique” while playing an accordion [“My Old Kentucky Home,” Season 3, Episode 3]). Megan’s “Zou bisou bisou” routine recalls Brigitte Bardot’s famous over-the-top dance in the 1956 …And God Created Woman — and while Megan is not as curvy or brilliantly seductive as BeBe (earlier, she admits to being a bad actress), the dance is excessive in the same way, breaking the bourgeois codes of propriety by turning on all the men in the room, except for Don. As is typical for Mad Men, the dance is then performed again and again as a kind of comic/traumatic repetition: first by Roger, then by Harry, then by Lane.

Don’s concern over being the butt of a joke (“You’re wondering what they’re laughing about. It’s not you,” Roger tells him; but a few scenes later, admits that he is in fact making fun of him). On some level, Don understands that his impulsive marriage to a woman nearly half his age makes him both comical and clichéd. His defense mechanism is to exercise total control over the woman he’s married, making sure that he is still our man: he demands that Megan open her blouse in his office, assumes that his own work schedule always takes priority (even when it seems he has nothing to do), and uses a fair amount of force to subdue his sex-kitten-turned-pouty-teenager. (As Don famously says to Ken in “The Hobo Code,” “you’ll realize in your private life that at a certain point seduction is over, and force is actually being requested.” [Season 1, Episode 8])

This concern over being the butt of a joke leads us back to the prank with which the episode started—the ad execs throwing water bombs out the Y& R office window. Y & R’s childish prank becomes a sign of their immaturity and bigotry, yet, in this episode, it is also an interesting device because it accomplishes, in a subtle way, a crossing of a racial divide that brings the problem of race “home,” or in this case, from the street into the office. To rub salt in their competitor’s wounds, Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce puts an ad in the Times claiming to be “An equal opportunity employer. Our windows don’t open. We are committed to proving that Madison Avenue isn’t all wet.” Rather than Y & R, however, Joan becomes the ad’s first victim, assuming that it is meant as an advertisement for her own position. Reassured by Lane that she is as needed as ever, she tries to put into words her feeling of isolation: while Lane assures her that “Nothing’s happened,” she reminds him that, “Something always happens. Things are different. Someone tells a joke and you don’t know what they’re talking about.” “There’ve been no jokes, not without you,” Lane says. “Not even at my expense?” Joan asks.

The “equal opportunity” ad is of course a joke precisely at her expense, as a series of humiliations precede the revelation of truth. While Joan initially suspects that the ad is not real, she nevertheless brings the baby to the office to see for herself — and her first set of encounters, from difficulties opening the door, to a receptionist who has never heard of her, to learning that her job is being handled by two other secretaries — leads her to a tearful breakdown in Lane’s office. (As Mary Jacobus has long ago argued, a joke is almost always at woman’s expense.Indeed, as the episode draws to a close, SCDP is in fact in the process of hiring a new girl — and the imaginary threat of replacement is made real.)

But while Joan may be the joke’s first victim, she is not its only one. Because by the time the episode is over, the joke has played out to its logical conclusion: stepping out the elevator, Don and Megan find that the SCDP lobby is full of job seekers, black men and women who have answered the want ad. While SCDP thought it was addressing itself to its competition, it was really hailing a very different group — unconsciously, it was speaking to the group that we see picketing outside the Madison Avenue offices. For the first time ever, I think, Mad Men has a message, and it is about the fact that the outside world is about to be brought inside.

The letter, Lacan says, always arrives at its destination.