|

| Leo Burnett’s 1968 ad for Virginia Slims |

"You've Come a Long Way, Baby"

Guest Writers: Lauren M. E. Goodlad (English/Unit for Criticism) and Caroline Levine (Wisconsin)

In a plangent moment from Season 5’s finale, “The Phantom,” Pete Campbell tells his story to a lover who believes she is talking to a stranger. It is the second time this season that Pete’s life has become the subject of fiction: in “Signal 30” (5.5) he was the inspiration for Ken’s transition from science fiction to a bleak narrative of suburban despair. It is all the more fascinating, then, that the opportunity to tell his own tale finds Pete describing himself as the would-be hero of a rather different genre, the Bildungsroman. That is, when Beth asks why Pete’s “friend” had an affair, he replies: “Well…he needed to let off some steam, he needed adventure….he needed to feel that he knew something, that all this aging was worth something because he knew things young people didn’t know yet.”

This gesture toward Bildung is important to Mad Men’s viewers for at least two reasons. According to Franco Moretti, the Bildungsroman—usually translated as the “novel of development”—is modernity’s archetypal narrative form. That is to say, while the actual conditions of modernity entail never-ending transformation subject to the demands of technological and economic change, youth’s destiny (as in the classic examples of Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister or Austen’s Elizabeth Bennet), is to mature. The function of the Bildungsroman, therefore, is to reconcile youthful desire to social demands and--in so doing--to portray modernity’s ceaseless change through the guise of a human story of meaningful growth and compromise. The function of the Bildungsroman, in other words, is to make men like Pete believe that “all this aging is worth something.”

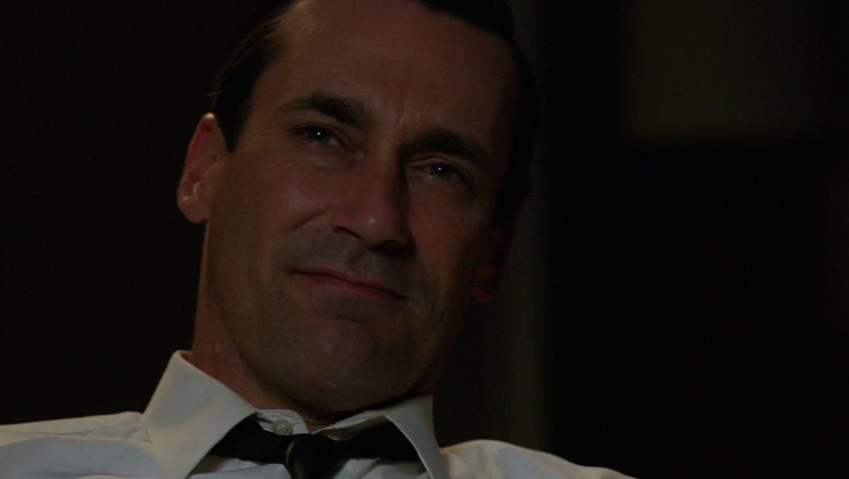

For the very same reason, Mad Men has generally resisted this formal compromise: the show has been a “Bildungsroman without the Bildung,” or as Lilya Kaganovsky wrote in her post on this season’s premiere, a series in which “nobody grows wiser,” “only older.” That has especially been the case for Don who, while never quite young, has managed to trump the ephemerality of youth through seemingly boundless self-invention. At the end of Season 4, when Don impulsively proposed to a young woman he hardly knew, he seemed more than ever to be rejecting maturity (Faye Miller) in favor of a fantasy of self-creation.

For the very same reason, Mad Men has generally resisted this formal compromise: the show has been a “Bildungsroman without the Bildung,” or as Lilya Kaganovsky wrote in her post on this season’s premiere, a series in which “nobody grows wiser,” “only older.” That has especially been the case for Don who, while never quite young, has managed to trump the ephemerality of youth through seemingly boundless self-invention. At the end of Season 4, when Don impulsively proposed to a young woman he hardly knew, he seemed more than ever to be rejecting maturity (Faye Miller) in favor of a fantasy of self-creation.But Season 5 has had more than a few surprises.

The season has in many ways seen Mad Men itself mature from Don Draper’s story into a thicker multiplot narrative: the story, for example, of Joan’s move into single motherhood, Peggy’s into unmarried cohabitation, Roger’s into turning on and tuning in, and Betty’s into group self-help. We will return to these mid-60s narratives but the point for now is that Don’s shift from Nietzschean Ubermensch to part of an ensemble cast has enabled him to mature like the hero of a Bildungsroman.

The season has in many ways seen Mad Men itself mature from Don Draper’s story into a thicker multiplot narrative: the story, for example, of Joan’s move into single motherhood, Peggy’s into unmarried cohabitation, Roger’s into turning on and tuning in, and Betty’s into group self-help. We will return to these mid-60s narratives but the point for now is that Don’s shift from Nietzschean Ubermensch to part of an ensemble cast has enabled him to mature like the hero of a Bildungsroman. From the start, we could see that Don’s marriage to Megan was not the reprise of his first marriage which last season’s finale had seemed to augur. Whereas Megan the Secretary had won Don with her blend of seductress and Maria von Trapp, the Megan of Season 5 is a career woman whose mother scolds her for refusing to bear children. The season began with the intriguing premise of a marriage that obviated the need for an office romance as the new Mrs. Draper chose advertising (and the occasional workplace quickie) over childrearing in suburbia. But even as Megan’s “Zou bisous” number both embarrassed and enchanted her man, it made clear that performance was her true métier. Don’s growth has thus taken multiple forms: wrestling with fantasy demons in “Mystery Date”; passing up real-life prostitutes in “Signal 30”; learning to enjoy Megan as more than his personal sidekick and good luck charm; and, in one of the most powerful episodes of the season, accepting Megan’s decision to leave advertising for “her dream.”

From the start, we could see that Don’s marriage to Megan was not the reprise of his first marriage which last season’s finale had seemed to augur. Whereas Megan the Secretary had won Don with her blend of seductress and Maria von Trapp, the Megan of Season 5 is a career woman whose mother scolds her for refusing to bear children. The season began with the intriguing premise of a marriage that obviated the need for an office romance as the new Mrs. Draper chose advertising (and the occasional workplace quickie) over childrearing in suburbia. But even as Megan’s “Zou bisous” number both embarrassed and enchanted her man, it made clear that performance was her true métier. Don’s growth has thus taken multiple forms: wrestling with fantasy demons in “Mystery Date”; passing up real-life prostitutes in “Signal 30”; learning to enjoy Megan as more than his personal sidekick and good luck charm; and, in one of the most powerful episodes of the season, accepting Megan’s decision to leave advertising for “her dream.”Less compromise than bitter pill, Don has struggled with his wife’s craving for the life of the artist. On the one hand it means that she wants more than the material fulfillment he provides, or the children he would readily father (after his fashion). But even worse, Megan’s decision wounds Don’s self-esteem in making advertising something very much less than one’s “dream.” (Though he has never romanticized advertising neither has he ever loved a woman who put herself above it—even Rachel, Don’s beloved in Season 1, was content with the business world.) Careful to spare Megan the full brunt of his anger, Don has vented his feelings at Peggy, his true comrade in arms and a woman who knows that plenty of people would “kill” for a job in advertising.

Don’s “novel of development” has thus been put to the test. In last week’s episode, he repeated past mistakes, ignoring Lane’s cry for help. Now, (in yet another episode that finds him hallucinating under the effects of fever), Don “sees” the abandoned brother who hanged himself in a New York hotel room. In Season 1 he tried to buy off Adam with “5G,” the store of cash he kept in his drawer for such dreadful emergencies. In “The Phantom” it is Lane’s wife whom Don hopes to appease and his offer this time is upped to 50G. But Rebecca, still tragically unaware that Lane had struggled to support their lifestyle, blames Don for stoking her husband’s lust and ambition. She believes that Dolores (whose photo Lane kept in his wallet), was a real mistress and not a fantasy lover whom Lane never met.

Don’s “novel of development” has thus been put to the test. In last week’s episode, he repeated past mistakes, ignoring Lane’s cry for help. Now, (in yet another episode that finds him hallucinating under the effects of fever), Don “sees” the abandoned brother who hanged himself in a New York hotel room. In Season 1 he tried to buy off Adam with “5G,” the store of cash he kept in his drawer for such dreadful emergencies. In “The Phantom” it is Lane’s wife whom Don hopes to appease and his offer this time is upped to 50G. But Rebecca, still tragically unaware that Lane had struggled to support their lifestyle, blames Don for stoking her husband’s lust and ambition. She believes that Dolores (whose photo Lane kept in his wallet), was a real mistress and not a fantasy lover whom Lane never met. When Don meets Peggy at the movies, it signals the real growth this season has entailed: the “little girl” who was once his protégé has learned Don’s lessons so well she can stand (and stand taller) without him. “That’s what happens when you help someone,” Don says ruefully, “They succeed and move on.” His words pinpoint the little tragedy behind every coming-of-age (reminding us that Don’s daughter Sally will also move on to her own stories soon).

When Don meets Peggy at the movies, it signals the real growth this season has entailed: the “little girl” who was once his protégé has learned Don’s lessons so well she can stand (and stand taller) without him. “That’s what happens when you help someone,” Don says ruefully, “They succeed and move on.” His words pinpoint the little tragedy behind every coming-of-age (reminding us that Don’s daughter Sally will also move on to her own stories soon). There are ironies here, to be sure. Peggy’s work on a cigarette account that, in real life, culminated in Leo Burnett’s famous 1968 campaign –“You’ve come a long way”--points to a commodified illusion of feminist liberation which sells short the real thing. Framed by advertising's core task of wresting human feeling from desire for products, Peggy’s Bildungsroman is a compromise indeed, not to mention a likely way to get cancer. But like Joan’s comparable ascent to power, success comes differently to this generation of women than to the white middle-class Dons, Petes, and Harries whose lesser struggles afford them the sad luxury of deeper yearning. Yes, Don’s youthful dream was “indoor plumbing” but that was (quite literally) another life. The Don who has outgrown the need to hide his past from his wife knows that advertising sells desire for what does not actually exist—like the spotless white carpet he spoke of in “A Little Kiss.” As creative director, Don has spent his life freeze-framing images of joy like the family photos he used to pitch the Kodak carousel. What Marie says to Don about her daughter (who has been drowning her sorrows in drink) cannot be lost on Don: “This is what happens when you have the artistic temperament but you are not an artist."

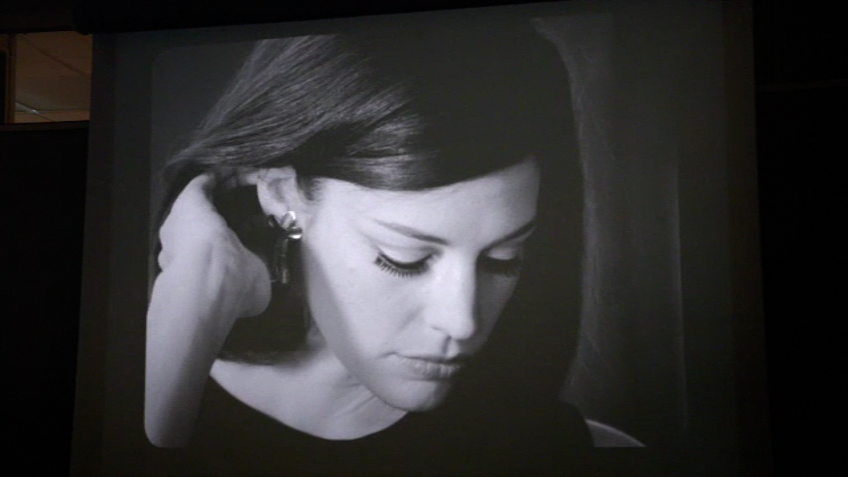

There are ironies here, to be sure. Peggy’s work on a cigarette account that, in real life, culminated in Leo Burnett’s famous 1968 campaign –“You’ve come a long way”--points to a commodified illusion of feminist liberation which sells short the real thing. Framed by advertising's core task of wresting human feeling from desire for products, Peggy’s Bildungsroman is a compromise indeed, not to mention a likely way to get cancer. But like Joan’s comparable ascent to power, success comes differently to this generation of women than to the white middle-class Dons, Petes, and Harries whose lesser struggles afford them the sad luxury of deeper yearning. Yes, Don’s youthful dream was “indoor plumbing” but that was (quite literally) another life. The Don who has outgrown the need to hide his past from his wife knows that advertising sells desire for what does not actually exist—like the spotless white carpet he spoke of in “A Little Kiss.” As creative director, Don has spent his life freeze-framing images of joy like the family photos he used to pitch the Kodak carousel. What Marie says to Don about her daughter (who has been drowning her sorrows in drink) cannot be lost on Don: “This is what happens when you have the artistic temperament but you are not an artist." “The Phantom” turns out to reveal that this season, above all, has been Megan’s Bildungsroman--though not in the “happily ever after” way of Elizabeth Bennet. Her passion for acting finds Megan trapped in the bind so hauntingly captured in the James Bond theme that closes this season: “This dream is for you, so pay the price.” As we learned two weeks ago, that price is the readiness to throw your soul into the bargain of selling your labor. It is the price Joan paid to earn her seat at the table of a firm now enjoying its best quarter yet; it is the price Megan knows is at stake after yet another audition under ogling male eyes.

“The Phantom” turns out to reveal that this season, above all, has been Megan’s Bildungsroman--though not in the “happily ever after” way of Elizabeth Bennet. Her passion for acting finds Megan trapped in the bind so hauntingly captured in the James Bond theme that closes this season: “This dream is for you, so pay the price.” As we learned two weeks ago, that price is the readiness to throw your soul into the bargain of selling your labor. It is the price Joan paid to earn her seat at the table of a firm now enjoying its best quarter yet; it is the price Megan knows is at stake after yet another audition under ogling male eyes.Will Megan succeed, mature—come of age? Her struggle for independence looks at times like the classic Bildung plot. But she ends season 5 with an ironic version of a happy fairytale ending. Don, the rich and powerful king, falls in love with the poor neglected Beauty on film and gives her what she longs for. The coveted commercial role grants Megan her wish, but its fulfillment comes at a double cost: a reliance on a husband to make her dreams come true, and a return to the sordid world of advertising, the very world she had abandoned for the autonomy and integrity of art.

Megan's desire to become the "European type" for Butler shoes takes us back to Season 1's “Shoot” (1.9), in which Betty longs to revive her modeling career in a spot for Coca Cola. As Don knows, the choice of Betty for the ad is part of another agency’s gambit to lure him. Thus, in an ironic foreshadowing, the young Don does not suffer his wife's wish for a life outside marriage. When Betty is fired from the Coke shoot without knowing why, she tries to console herself with household chores -- with results that we all remember. As yet, Megan has needed no similar recourse: but she has only begun to feel that sex “is the only thing [she is] good for.” And unlike Betty, she has not (yet) felt the sting of a husband’s infidelity.

Megan's desire to become the "European type" for Butler shoes takes us back to Season 1's “Shoot” (1.9), in which Betty longs to revive her modeling career in a spot for Coca Cola. As Don knows, the choice of Betty for the ad is part of another agency’s gambit to lure him. Thus, in an ironic foreshadowing, the young Don does not suffer his wife's wish for a life outside marriage. When Betty is fired from the Coke shoot without knowing why, she tries to console herself with household chores -- with results that we all remember. As yet, Megan has needed no similar recourse: but she has only begun to feel that sex “is the only thing [she is] good for.” And unlike Betty, she has not (yet) felt the sting of a husband’s infidelity. As Don looks at Megan on celluloid and loves her more than the flesh-and-blood wife who has rejected his art, we perceive a return to the Kodak carousel—an image of love far more perfect than anything life has to offer. For the moment at least, Megan has literally become Betty: a woman at a “shoot” controlled by Don. It is perhaps no wonder that the episode ends with an Emily look-alike propositioning Don--as though Emily herself were exacting revenge. We will soon enough find out if “Don doesn’t do that.” After all, you only live twice.

As Don looks at Megan on celluloid and loves her more than the flesh-and-blood wife who has rejected his art, we perceive a return to the Kodak carousel—an image of love far more perfect than anything life has to offer. For the moment at least, Megan has literally become Betty: a woman at a “shoot” controlled by Don. It is perhaps no wonder that the episode ends with an Emily look-alike propositioning Don--as though Emily herself were exacting revenge. We will soon enough find out if “Don doesn’t do that.” After all, you only live twice. As it turns out, ironic fairytale endings are not only for women. Pete has been begging Trudy for an apartment in the city and his wish also comes true. It is his eagerness for erotic adventure that prompted his desire for an apartment in the first place, but it is the end of the affair with Beth that grants him his desire. Pete comforts himself by blaming Howard, whom he casts as the Beast in his own Beauty story: “He wants to control you. He’s a monster!” he cries, conveniently disregarding the fact that Beth herself willingly chooses electroshock treatment. If Megan’s neat ending takes as much away from her dreams as it grants them, Pete’s preference for the fairytale is a way of comforting himself with a sense of his own strength and virtue. Men can be handsome princes come to save women from wicked fates, or they can be cruel beasts. And Pete, of course, likes to think of himself as the handsome and virtuous hero.

Roger, too, has been pursuing some magical wishes. Marie’s dalliance with him has given Roger a sense that she is adventurous enough to keep him company while he takes another dose of LSD. But she is no fairy godmother. “Please don’t ask me to take care of you,” she says. She repeats this refusal to Don, who is angry with her for not taking better care of Megan. “She’s married to you—that’s your job,” Marie tells him calmly.

Here, in fact, is the real lesson of both the fairytale and the classic Bildungsroman. Both center on the desire for social ascent. But what or who makes it possible for someone to rise? We might think of Balzac’s Rastignac, the social climber who charms and seduces his way into high society, or about Bronte’s Jane Eyre, whose quick mind and self-reliance help her shift from penniless, rejected orphan to comfortable wife and mother. In granting wealth and status to their protagonists, these novels are not so far from fairytales like Cinderella or Beauty and the Beast. Critics have often distinguished the Bildungsroman from the fairytale in arguing that the novel celebrates a consummately modern individualism, understanding the protagonist as using her own wits and independence to climb the social ladder, while the fairytale points to magic and mediation. Literary critic Bruce Robbins has recently argued, however, that even the most isolated heroes of the Bildungsroman don’t do it all on their own. They rely on benefactors of some kind—wise mentors, rich uncles, and even well-connected husbands—to facilitate their rise. For Robbins, the Bildungsroman actually points to the impossibility of a genuinely independent rise, and so suggests a political lesson not unlike the argument recently made famous by Elizabeth Warren:

You built a factory out there? Good for you. But I want to be clear: you moved your goods to market on the roads the rest of us paid for; you hired workers the rest of us paid to educate; you were safe in your factory because of police forces and fire forces that the rest of us paid for. You didn't have to worry that marauding bands would come and seize everything at your factory, and hire someone to protect against this, because of the work the rest of us did.

On some level, Mad Men knows this and has always known it. Don’s rise has depended on Dick Whitman’s “death”; Pete’s on family connections; Joan’s on men’s desire; Megan’s on Don’s intercession. Even Peggy, now the forbidding boss of young male copywriters, has relied on Don’s mentorship (“Just knocking out the cobwebs. Someone told me this works.”). When Rebecca Pryce reproaches Don--“You had no right to fill a man like that with ambition” she says—-she makes clear that even the desire to rise is itself a social, collective fact—-something that advertisers know all too well. In so many of these examples, Don, the self-made man who has had crucial help from others, plays a part in the Bildung of those coming along behind him. In some sense, after all, he has always been part of an ensemble plot.

But mostly Mad Men foregrounds disconnection and separation, and the season finale remorselessly hammers this home. The women seek independence. The men feel alone. Characters long for connection, but don’t know how to make that work. How can Megan connect to Don across his resentment, and Don across Megan’s urge for autonomy? “You can’t even kiss me?” Megan asks, appalled at their distance. “Don’t go, don’t leave me,” Don begs the hallucination of his dead brother. Joan marks the spot on the carpet where the two floors of the firm will connect, but for now they remain separate. “Mind your own business for once,” she admonishes Harry Crane in the elevator, itself a container that both separates and connects. After shock treatment it is Beth who seeks connection with Pete, but now they are strangers exchanging pleasantries. “Please, please keep me company,” she asks politely. “Nice to meet you,” Pete says as he leaves.

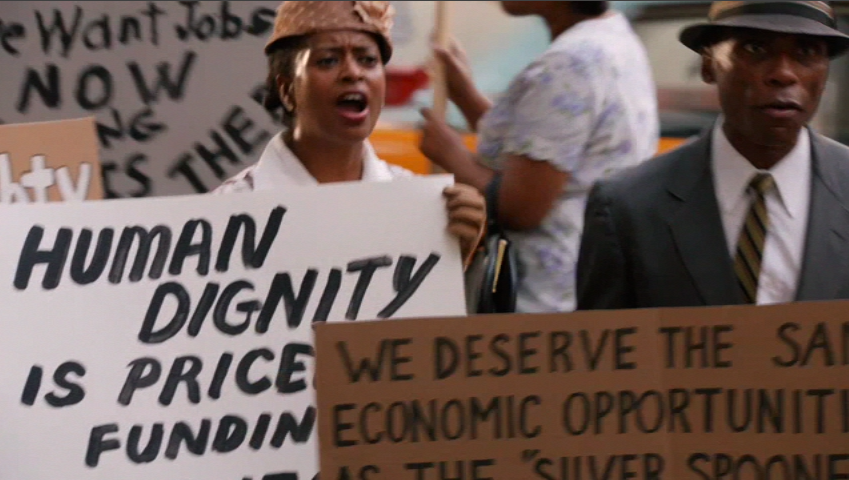

But mostly Mad Men foregrounds disconnection and separation, and the season finale remorselessly hammers this home. The women seek independence. The men feel alone. Characters long for connection, but don’t know how to make that work. How can Megan connect to Don across his resentment, and Don across Megan’s urge for autonomy? “You can’t even kiss me?” Megan asks, appalled at their distance. “Don’t go, don’t leave me,” Don begs the hallucination of his dead brother. Joan marks the spot on the carpet where the two floors of the firm will connect, but for now they remain separate. “Mind your own business for once,” she admonishes Harry Crane in the elevator, itself a container that both separates and connects. After shock treatment it is Beth who seeks connection with Pete, but now they are strangers exchanging pleasantries. “Please, please keep me company,” she asks politely. “Nice to meet you,” Pete says as he leaves. The whole season ends with the question, “Are you alone?” It is a real question. An urgent question. It is a question about how one succeeds and makes money, and a question about intimacy and care. It is a question of economics and of love. It is a question of genre. It is also a question of politics. And it is here that Mad Men does not deliver on its promise. The season opened with a civil rights march, hinting at a kind of collectivity that it left completely unexplored. What civil rights teaches us is that we are never alone. We belong to groups separated by racial privilege and exclusion. Those who are excluded by race can rise if they band together, demanding rights and access denied to them. Far from a fairytale, this was exactly what was happening on the streets in 1966-67. But Mad Men keeps to ironic fairytales and Bildungsromane. It has yet to find a genre to tell the political story that is begging to be told. But it should. Because politically speaking, you are never alone. You've come a long way baby. But don't kid yourself that you can do it alone.

The whole season ends with the question, “Are you alone?” It is a real question. An urgent question. It is a question about how one succeeds and makes money, and a question about intimacy and care. It is a question of economics and of love. It is a question of genre. It is also a question of politics. And it is here that Mad Men does not deliver on its promise. The season opened with a civil rights march, hinting at a kind of collectivity that it left completely unexplored. What civil rights teaches us is that we are never alone. We belong to groups separated by racial privilege and exclusion. Those who are excluded by race can rise if they band together, demanding rights and access denied to them. Far from a fairytale, this was exactly what was happening on the streets in 1966-67. But Mad Men keeps to ironic fairytales and Bildungsromane. It has yet to find a genre to tell the political story that is begging to be told. But it should. Because politically speaking, you are never alone. You've come a long way baby. But don't kid yourself that you can do it alone.