[The second in the Unit for Criticism's multi-authored series of posts on Season 5 of AMC'sMad Men,prior to the publication of MAD MEN, MAD WORLD: Sex, Politics, Style, and the 1960s (Duke University Press) Eds. Lauren M. E. Goodlad, Lilya Kaganovsky and Robert A. Rushing]

"Blindness and Insight"

Written by Robert A. Rushing (Comparative Literature, Italian, Cinema and Media Studies)

“Tea Leaves,” the follow-up to last week's Season 5 premiere, is a curious episode for Mad Men: it is less tightly organized thematically than most episodes of the series are. There is some suggestion, however that the episode is more tightly structured than might first appear—it begins and ends (or more precisely, almost begins and almost ends) with two sequences of people speaking in a foreign language, left untranslated for the viewer. The second sequence and the second to last sequence feature Megan speaking French, and Michael’s father speaking Hebrew. Megan’s conversation is banal, about the July heat and how she misses her mother; Michael’s father is performing a blessing, of course—but one could hardly say that the episode is about the transformation of the everyday into the sacred. In between these near bookends, we follow Peggy hiring a new copy writer; Don and Harry on a wild-goose chase to get the Rolling Stones to sing about Heinz beans; the continuing humiliation of Roger Sterling by Pete Campbell; and of course, the show’s primary plotline, the one that really bookends the episode, Betty’s weight gain and subsequent cancer scare.

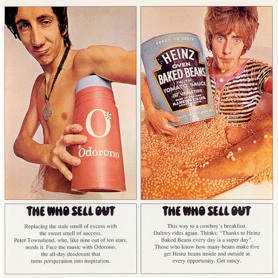

(By the way, the idea of co-opting youth culture and rock-and-roll for selling banal household goods—specifically the ludicrous idea of trying to connect British rockers to Heinz beans—would be definitively mocked on the front cover of The Who’s The Who Sell Out, released the following year, 1967. The Who were in fact doing precisely such commercial jingles even at that time, however, long before they provided the theme song for C.S.I. One of the many things I love about Mad Men is that so many of the show’s most bizarre and ludicrous advertising campaigns, obviously fictional, turn out to be entirely real.)

The sequence that gives this episode its title, however, consists of Betty and her old friend Joyce having tea—perhaps the episode’s “thematic core” may be found there. They talk about the cancer Betty may have, and the cancer that Joyce does have. Their conversation is perhaps more about the present than it is about the future—indeed, Joyce talks rather distantly about living with and fighting against her cancer as a kind of eternal drowning, one you give into, sooner or later. Her tea leaves cannot spell out any future, since she is living without one.

Then “Cecilia” arrives—a fortuneteller, to provide the ladies with some amusement (”it’s always good,” Joyce says, urging Betty to play along). She offers to read Betty’s tea leaves, and pronounces: “You’re a great soul. You mean so much to the people around you. You’re a rock—” but breaks off when she realizes that Betty has broken down. The name Cecilia comes from the Latin word for “blind” (caecus), and one might wonder just how blind Cecilia is, and what kind of blindness she represents (one might wonder as well about the various forms of blindness that run through this episode, from Roger’s failure to see that he was being played by Pete to Harry’s inability to distinguish the Trade Winds from the Rolling Stones). On the one hand, Cecilia’s attempt to see the truth of Betty appears as an almost comic failure: Betty? A great soul? Has anyone on television ever been as brilliantly self-centered and small-minded as Betty? A rock? (When Roger calls her “a fighter,” Don snorts, rolls his eyes and says, “Come on.”) As for how much she means to people around her (exception, perhaps, for Henry Francis), when Don informs Roger that Betty has cancer, Roger morbidly quips: “well, that would solve everything”—and if we laugh at all, it’s because we realize how close that is to being true, both for Don and for the show.

(What is this show to do with Betty? It cannot keep her, so wholly divorced from all of the rest of the show now that she is divorced from Don, and yet she is part of the essential iconography of Mad Men, and a favorite target—albeit a negative one—for audience identification. Betty is one of contemporary television’s most hated characters, pronounced on countless blogs as “worst mother ever,” but this is also part of what brings viewers back to the show: how will she mistreat Sally to gratify her own petty needs this week? And indeed, some fans reacted with predictable glee to Betty’s misfortunes in this episode. But one has to wonder if Betty’s cancer scare isn’t also Mad Men’s way of fantasizing about getting rid of this increasingly heavy burden. As it stands, the show seems forced to relegate her to an occasional “Betty-centric” episode that presents her totally separate existence, connected to the world of SCDP only by the rare phone call.)

But perhaps, as with Tiresias, one kind of blindness is another kind of insight—perhaps Cecilia’s failure to see the true nature of Betty’s interior is symptomatic of Mad Men’s long-standing concern not with depths, but with surfaces. The show may have derived all kinds of recognition for its superficially appealing qualities (set design, historical mimicry, meticulous mise-en-scène, dandies in slim suits and full-figured women, and so on), but it was curiously insightful from the beginning that the clothes really do make the man, in a quite literal fashion. The most salient example, of course, is Don’s ability to drape himself with the right clothes and the right name and the right identity really do transform him from a nobody, a whit of a man, into a Don, a minor title of nobility; or the way the credit sequence tells that same story in a miniaturized, even more superficial form—an outline of a man dissolves, collapses, and re-forms himself. It could be Don, or Roger (”exhausted from hanging on to the ledge”), or even Betty. So we should look for “the truth” of this sequence not in Cecilia’s facile fortune cookie, but in the specific exterior form that her fortune-telling takes: reading tea leaves.

Betty’s very precise fear in this episode indeed revolves around bitter remainders: “I’m leaving behind such a mess,” she confesses to Joyce—but about her life, not her tea—”he’s my second husband… his mother’s domineering and… Don’s girlfriend—well, they’re married—she’s twenty years old. They’ll never hear a nice word about me again.” She is unhappy both with what she will leave behind, and what will remain of her: bitter words, recriminations, her shortcomings and failures, all pronounced by a chorus of her mother-in-law, her ex-husband and his new, younger wife. Later, in a dream sequence (Don has flashbacks, but is it only Betty who has surreal hallucinations and dream sequences?), Betty will imagine a mise-en-scène of these remainders (it is unclear if she dreams or simply fantasizes while unable to sleep). She enters the kitchen to find her family dressed in mourning. Her husband intones his own series of bitter remainders, fragments of what could have been: “If, if, if,” and Betty glances down to see an emptied tea cup at her son’s side. Sally takes her mother’s chair and sets it, upside-down, on the table, like a restaurant after closing time. All the while, her mother-in-law serves breakfast and watches. They are the remainder, what is left over after Betty is consumed by the cancer we will soon discover she doesn’t have.

(A commenter on the last post noted that Lane’s fantasy photo of Dolores might have been a reference to Nabokov’s Lolita. I keep wondering about Henry Francis’ curious and enigmatic “If, if, if…” at the breakfast table, and thinking that it was perhaps a call-out to the big if, the great maybe, the I.P.H.—Institute of Preparation for the Hereafter—from Nabokov’s 1962 Pale Fire. Obligatory Nabokov reference accomplished!)

Naturally, it’s no accident that all of these images—the tea cup, the chair upended like a restaurant, the funereal breakfast of pancakes and sausages that Betty can’t share even though she is hungry—revolve around food; the show’s central premise, also a kind of tragic visual gag, is that Betty has gotten fat (January Jones was pregnant at the time the episode was filmed, but was also wearing a fat suit). All of these are remainders produced by Betty’s excess of consumption (not, perhaps, unlike the empty bag the stoned Harry leaves Don holding after he scarfs down twenty sliders).

The end effect is a kind of miracle for viewers of the show—without changing Betty’s essential nature at all, “Tea Leaves” manages to almost humanize this character whom audiences have long loved to hate. She is still a tough pill to swallow (”It’s nice to be put through the wringer and find out I’m just fat,” she snaps bitterly at her husband’s happiness, when he discovers she doesn’t have cancer), just as self-centered, and just as infantile (she still calls Don for reassurance, and it’s no accident that she eats the ice cream sundae her daughter has grown too mature for while “Sixteen Going on Seventeen” gives the viewers a sound bridge into the credits). Betty ends the episode curiously contented, however, sitting in the chair imaginary Sally overturned, happily polishing off her daughter’s sundae while ice cream drips from her spoon onto the table: the bitter dregs of her life have become something sweeter, and Betty seems determined that this time, nothing will be left over.

"Blindness and Insight"

Written by Robert A. Rushing (Comparative Literature, Italian, Cinema and Media Studies)

“Tea Leaves,” the follow-up to last week's Season 5 premiere, is a curious episode for Mad Men: it is less tightly organized thematically than most episodes of the series are. There is some suggestion, however that the episode is more tightly structured than might first appear—it begins and ends (or more precisely, almost begins and almost ends) with two sequences of people speaking in a foreign language, left untranslated for the viewer. The second sequence and the second to last sequence feature Megan speaking French, and Michael’s father speaking Hebrew. Megan’s conversation is banal, about the July heat and how she misses her mother; Michael’s father is performing a blessing, of course—but one could hardly say that the episode is about the transformation of the everyday into the sacred. In between these near bookends, we follow Peggy hiring a new copy writer; Don and Harry on a wild-goose chase to get the Rolling Stones to sing about Heinz beans; the continuing humiliation of Roger Sterling by Pete Campbell; and of course, the show’s primary plotline, the one that really bookends the episode, Betty’s weight gain and subsequent cancer scare.

(By the way, the idea of co-opting youth culture and rock-and-roll for selling banal household goods—specifically the ludicrous idea of trying to connect British rockers to Heinz beans—would be definitively mocked on the front cover of The Who’s The Who Sell Out, released the following year, 1967. The Who were in fact doing precisely such commercial jingles even at that time, however, long before they provided the theme song for C.S.I. One of the many things I love about Mad Men is that so many of the show’s most bizarre and ludicrous advertising campaigns, obviously fictional, turn out to be entirely real.)

The sequence that gives this episode its title, however, consists of Betty and her old friend Joyce having tea—perhaps the episode’s “thematic core” may be found there. They talk about the cancer Betty may have, and the cancer that Joyce does have. Their conversation is perhaps more about the present than it is about the future—indeed, Joyce talks rather distantly about living with and fighting against her cancer as a kind of eternal drowning, one you give into, sooner or later. Her tea leaves cannot spell out any future, since she is living without one.

Then “Cecilia” arrives—a fortuneteller, to provide the ladies with some amusement (”it’s always good,” Joyce says, urging Betty to play along). She offers to read Betty’s tea leaves, and pronounces: “You’re a great soul. You mean so much to the people around you. You’re a rock—” but breaks off when she realizes that Betty has broken down. The name Cecilia comes from the Latin word for “blind” (caecus), and one might wonder just how blind Cecilia is, and what kind of blindness she represents (one might wonder as well about the various forms of blindness that run through this episode, from Roger’s failure to see that he was being played by Pete to Harry’s inability to distinguish the Trade Winds from the Rolling Stones). On the one hand, Cecilia’s attempt to see the truth of Betty appears as an almost comic failure: Betty? A great soul? Has anyone on television ever been as brilliantly self-centered and small-minded as Betty? A rock? (When Roger calls her “a fighter,” Don snorts, rolls his eyes and says, “Come on.”) As for how much she means to people around her (exception, perhaps, for Henry Francis), when Don informs Roger that Betty has cancer, Roger morbidly quips: “well, that would solve everything”—and if we laugh at all, it’s because we realize how close that is to being true, both for Don and for the show.

(What is this show to do with Betty? It cannot keep her, so wholly divorced from all of the rest of the show now that she is divorced from Don, and yet she is part of the essential iconography of Mad Men, and a favorite target—albeit a negative one—for audience identification. Betty is one of contemporary television’s most hated characters, pronounced on countless blogs as “worst mother ever,” but this is also part of what brings viewers back to the show: how will she mistreat Sally to gratify her own petty needs this week? And indeed, some fans reacted with predictable glee to Betty’s misfortunes in this episode. But one has to wonder if Betty’s cancer scare isn’t also Mad Men’s way of fantasizing about getting rid of this increasingly heavy burden. As it stands, the show seems forced to relegate her to an occasional “Betty-centric” episode that presents her totally separate existence, connected to the world of SCDP only by the rare phone call.)

But perhaps, as with Tiresias, one kind of blindness is another kind of insight—perhaps Cecilia’s failure to see the true nature of Betty’s interior is symptomatic of Mad Men’s long-standing concern not with depths, but with surfaces. The show may have derived all kinds of recognition for its superficially appealing qualities (set design, historical mimicry, meticulous mise-en-scène, dandies in slim suits and full-figured women, and so on), but it was curiously insightful from the beginning that the clothes really do make the man, in a quite literal fashion. The most salient example, of course, is Don’s ability to drape himself with the right clothes and the right name and the right identity really do transform him from a nobody, a whit of a man, into a Don, a minor title of nobility; or the way the credit sequence tells that same story in a miniaturized, even more superficial form—an outline of a man dissolves, collapses, and re-forms himself. It could be Don, or Roger (”exhausted from hanging on to the ledge”), or even Betty. So we should look for “the truth” of this sequence not in Cecilia’s facile fortune cookie, but in the specific exterior form that her fortune-telling takes: reading tea leaves.

Betty’s very precise fear in this episode indeed revolves around bitter remainders: “I’m leaving behind such a mess,” she confesses to Joyce—but about her life, not her tea—”he’s my second husband… his mother’s domineering and… Don’s girlfriend—well, they’re married—she’s twenty years old. They’ll never hear a nice word about me again.” She is unhappy both with what she will leave behind, and what will remain of her: bitter words, recriminations, her shortcomings and failures, all pronounced by a chorus of her mother-in-law, her ex-husband and his new, younger wife. Later, in a dream sequence (Don has flashbacks, but is it only Betty who has surreal hallucinations and dream sequences?), Betty will imagine a mise-en-scène of these remainders (it is unclear if she dreams or simply fantasizes while unable to sleep). She enters the kitchen to find her family dressed in mourning. Her husband intones his own series of bitter remainders, fragments of what could have been: “If, if, if,” and Betty glances down to see an emptied tea cup at her son’s side. Sally takes her mother’s chair and sets it, upside-down, on the table, like a restaurant after closing time. All the while, her mother-in-law serves breakfast and watches. They are the remainder, what is left over after Betty is consumed by the cancer we will soon discover she doesn’t have.

(A commenter on the last post noted that Lane’s fantasy photo of Dolores might have been a reference to Nabokov’s Lolita. I keep wondering about Henry Francis’ curious and enigmatic “If, if, if…” at the breakfast table, and thinking that it was perhaps a call-out to the big if, the great maybe, the I.P.H.—Institute of Preparation for the Hereafter—from Nabokov’s 1962 Pale Fire. Obligatory Nabokov reference accomplished!)

Naturally, it’s no accident that all of these images—the tea cup, the chair upended like a restaurant, the funereal breakfast of pancakes and sausages that Betty can’t share even though she is hungry—revolve around food; the show’s central premise, also a kind of tragic visual gag, is that Betty has gotten fat (January Jones was pregnant at the time the episode was filmed, but was also wearing a fat suit). All of these are remainders produced by Betty’s excess of consumption (not, perhaps, unlike the empty bag the stoned Harry leaves Don holding after he scarfs down twenty sliders).

The end effect is a kind of miracle for viewers of the show—without changing Betty’s essential nature at all, “Tea Leaves” manages to almost humanize this character whom audiences have long loved to hate. She is still a tough pill to swallow (”It’s nice to be put through the wringer and find out I’m just fat,” she snaps bitterly at her husband’s happiness, when he discovers she doesn’t have cancer), just as self-centered, and just as infantile (she still calls Don for reassurance, and it’s no accident that she eats the ice cream sundae her daughter has grown too mature for while “Sixteen Going on Seventeen” gives the viewers a sound bridge into the credits). Betty ends the episode curiously contented, however, sitting in the chair imaginary Sally overturned, happily polishing off her daughter’s sundae while ice cream drips from her spoon onto the table: the bitter dregs of her life have become something sweeter, and Betty seems determined that this time, nothing will be left over.