[The fifth in the Unit for Criticism's multi-authored series of posts on Season 5 of AMC's Mad Men, posted prior to the publication of MAD MEN, MAD WORLD: Sex, Politics, Style, and the 1960s (Duke University Press) Eds. Lauren M. E. Goodlad, Lilya Kaganovsky and Robert A. Rushing]

"A Study in Orange"

Written by Lauren M. E. Goodlad (English/Unit for Criticism)

The title of Mad Men’s sixth episode this season, “Far Away Places,” echoes the 1948 Bing Crosby classic. But insofar as it leads viewers to anticipate the kind of glamorous business trip Don took with Betty in “Souvenir” (Season 3, Episode 8), the song’s yearning for real-life encounters with foreign lands is a feint. Although the episode explores far-off places of sorts, the journeys it takes in this rather complicated segment of Mad Men are more psychic and cultural than geographic. “Far Away Places” does not embark on real trips to Rome, or China, or Spain--though it does take us tripping. And in what has become a veritable leitmotif for Season 5, its most memorable tableaux are illusions.

Last week the show put us squarely in male fantasy terrain when Pete, hard at work with an obliging call girl, chose “You’re my king” over other equally tawdry clichés. Episode 6 opens with Abe’s suggesting that Peggy, nervous about her presentation for Heinz, join him at a showing of The Naked Prey. “You're gonna resist the chance to see Cornel Wilde naked?” he asks. Reviewing the movie in 1967, Roger Ebert called The Naked Prey the kind of “pure fantasy” in which an urbane white man, “set loose naked in the jungle,” discovers to his delight that he can “outrun half a dozen hand-picked African warriors.” Poor Abe. He has taken up Kinsey’s mantle of a white man engaged by the aspirations of the 60s with more humility than the often pompous Paul. Abe is clearly frustrated by Peggy’s distracted focus on work. But does he really want to see this movie?

In a post on “Tomorrowland,” last season’s finale, Rob Rushing and I wrote that Don’s unpremeditated proposal during a trip to California signaled a kind of repetition compulsion. In works like his famous essay on the “pleasure principle,” Sigmund Freud contemplated the strange human compulsion to repeat disturbing experiences so as to create the illusion of mastery. Don’s sudden decision to marry his secretary, Rob and I noted, was marked as repetitious first by Roger (who applauded Don’s following in his own footsteps) and then by Joan who mused, “It happens all the time.” Viewers who had warmed to the maturity of Dr. Faye Miller rolled their eyes as Don tethered himself to yet another gorgeous projection of the idealized mother he never had. Would Megan turn out to be a crafty “actress” who had played her boss?

As yet, the answer seems to be no. Instead of a Don/Roger dyad, Season 5 has focused on aligning Pete Campbell with the Don of yore. As Eleanor Courtemanche noted in her great post on last week’s episode, Pete has become the star of a suburban saga: an unhappy commuter with all of Don’s former wonderlust and little of his charm. By contrast, Megan, whose supposed love of children has vanished without a trace, is hardly eager to make babies in “the country.” In fact, unlike consummate trophy wife Jane Sterling, Megan is genuinely invested in work. More like Ken and Cynthia than Roger and Jane, the New Drapers could relate to one another as fellow professionals as well as husband and wife. Could, that is, if Don truly considered Megan a colleague like Peggy. But does he?

The question is part of the sustained meditation on upper-middle-class life which the season has so far dwelled on. Upping that ante, “Far Away Places” experiments with narrative techniques for depicting what the anthropologist Benedict Anderson calls simultaneity—the way that multiplot novels (and now serial television) engage modern time by creating “a complex gloss on meanwhile.” Juxtaposing three different couples—the Sterling/Draper doublet and the unmarried pair of Peggy and Abe-- the episode shows each twosome occupying the same slice of time. In a structure that could be called “Todayland,” time is rehearsed through the device of two literal “meanwhiles” to give us three different versions of the same roughly 24-hour period. The first is a scene of Don calling the office that only makes sense when we see it from his, not Peggy’s, perspective; the repetition of a second scene in which Don tells his secretary that he is away through the weekend, signals the shift from Sterling to Draper versions of the day.

Of course, Roger’s original plan was a different kind of pairing. On the morning of Peggy’s Heinz presentation, he proposes the kind of “completely debauched...‘fact-finding’ boondoggle” which (as Don reminds him) once landed him in the hospital after playing with twins (“Long Weekend,” Season 2, Episode 10). Entreating Don to join him on a road trip to Plattsburgh—home of the Howard Johnson’s “flagship”—Roger imagines a decadent escapade for “a couple of rich, handsome perverts.” But Don, who as Bert says is still on “love leave,” has a different idea of “playing hooky”--not an upstate hook-up but a Long Weekend with his wife. He leaves Roger both mocking and pining for his partner’s uxorious passion.

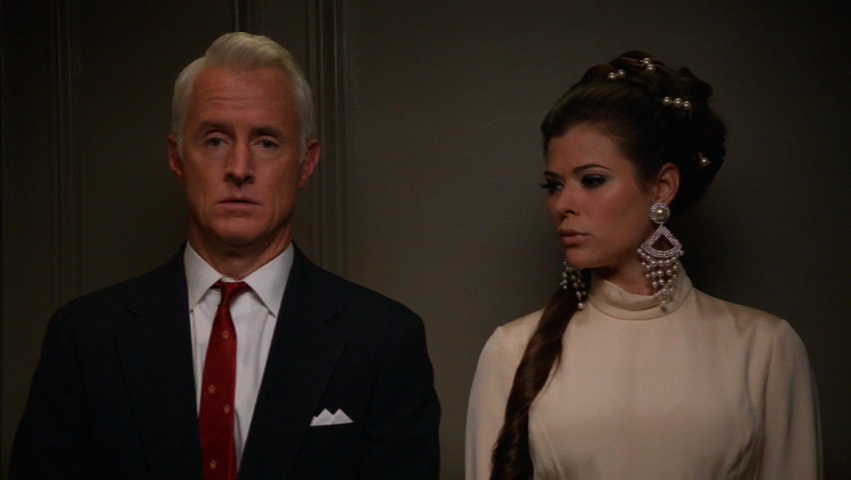

As Roger then rendezvouses with his own Mrs. in a marriage long past the honeymoon stage, he braces himself for dinner with her “snooty friends”—an evening that turns out to include existential philosophy, psychoanalysis, and LSD. Shaping Mad Men’s perspective on the budding trend for “turning on” and “tuning in,” Jane looks more like aStar Trek Goddess from Planet Up-Do than a hippychick at a Human Be-in. (All of these references are slightly ahead of the show’s current date, signaling, perhaps, that time is speeding up pace the teenager in Pete’s class in last week’s episode). At dinner, Jane’s shrink raises the compulsion to repeat: “I have patients who spend years reasoning out their motivation for a mistake and when they find it out they think they’ve found the truth.” Yet, they “go and make the same mistake.” As Rob and I noted, this same repetition compulsion underlies advertising’s hidden persuasion. By offering us empty illusions of having our cake and eating it too (like the ludicrous idea that eating beans makes us “included”), advertising invites us to hunker down with our neuroses.

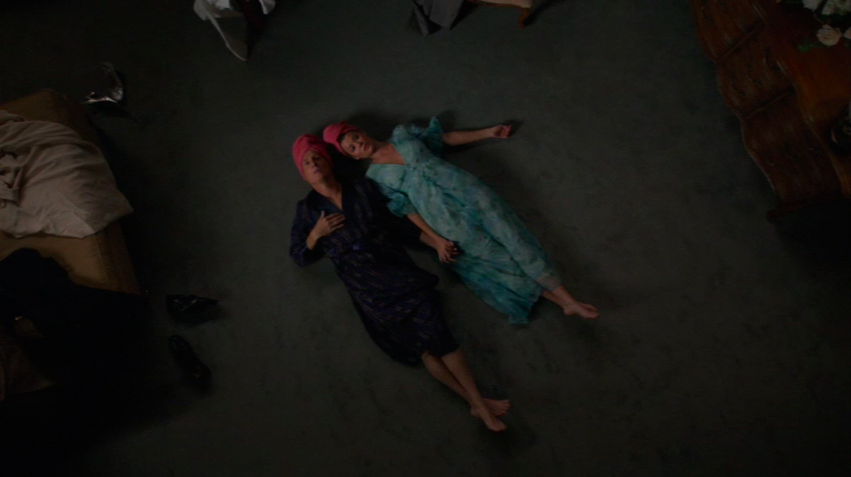

Still, dropping acid turns out to have a bigger impact on the Sterlings than any canned commodity could. After first writing off Dr. Leary’s invention as another boring “product,” Roger disregards his host’s advice, “Don’t look in the mirror.” The result is a series of hallucinations which culminates in Don’s ordering him to go to his wife “because she wants to be alone in the truth with you.” Having earlier received a kind of message in a bottle—“I’m Roger Sterling…PLEASE HELP ME”—Roger is ready to face the music even if “the truth” and “the good” are not the same thing. As they lie on the floor, gazing up into space, Mad Men captures the Sterlings’ truthiness through a languorous crane shot. When they wake up the next morning, we worry for a moment that the acid was talking, not Jane herself--until she concludes that “It’s going to be very expensive.” Free at last (in an episode in which Joan, tellingly, makes no appearance), Roger is more than ready to embrace another costly divorce. If he is no better than the man who left Mona in Season 2, neither is he very much worse.

"Meanwhile," the Sterlings’ denouement coincides with a conjugal road trip that has Don almost panting for the excitement he felt at Disneyland. When Megan worries about Peggy and Heinz, Don cajoles, “Remember California?” When she continues to demur, Don pulls rank: “I’m the boss. I’m ordering you” he says with a poke. Always ready to have his cake and eat it too, Don anticipates a “love leave” with a little labor on the side. But just as Peggy frustrated Abe with her focus on work, so Megan resists Don’s vacation vibe. When she expresses her guilty sense of letting down coworkers, Don speaks to her straight from the phallus: “There has to be some advantage to being my wife.”

The road trip in other words, is saturated with signals of impending failure—my favorite of which is the way it harks back to the fabulous trip to Rome in “Souvenir”, including Don’s buying actual souvenirs for his kids. When Don says to Megan, “I got something for you” and then holds up a plastic back scratcher, can anyone miss how the man who took his first wife to the Hilton in Rome now expects his new wife to feel the magic of a HoJo’s in Plattsburgh? (The contrast between Conrad Hilton and Dale Vanderwort is almost too cruel to emphasize.) Too late Megan’s mother reminds Don that his wife is allergic to gold alloy.

Vanderwort’s desire to roll out the “orange carpet” as muzak fills the air opens a scene that would be a surreal Study in Orange were Don himself not so tragically impervious to the irony. It is as though Don is reliving a childhood memory that neither we nor Megan can see (just as Jane can’t see Roger’s hallucination of a fondly remembered world series). When Don tells Megan with the straightest of faces, “The colors are bright and cheerful, the kids have candy, full bar for Mom and Dad: would you say it’s a delightful destination?”, it is momentarily unclear whether Don has simply collapsed the boundary of work and play or whether it isn’t after all him, not Roger, who’s been drinking the electric kool-aid—orange of course. "It's not a destination," Megan tells him "it's on the way to someplace."

By now, we can see it coming: “You like to work, but I can’t like to work,” Megan reasonably complains. If he has so far been lightly insufferable that is nothing to how Don behaves when told he’s been inconsiderate. And what perfect timing! The giant serving of orange sherbet he insisted on ordering arrives just in time to become the edible emblem for every infantile wish he has sunk into this bad trip. Predictably, Megan (despite her chic coral dress) does not like orange sherbet which tastes fake, “like perfume.” The waitress, (knowing the actual value of a Ho Jo’s) takes it in perfect stride. But as Megan orders chocolate, Don visibly experiences himself as a rejected flavor of frozen dessert, accusing her of embarrassing him. When Megan shows us that she really is a good actress, shoveling sherbet in her mouth in a performance that unnervingly recalls the fake orgasm scene in When Harry Met Sally we know that it is far too late to settle on another flavor. (This would be true even if Megan had not stumbled over the dreaded “m”-word asking Don about his [dead, prostitute] mother.)

What is clear long before the spat in the tangerine glow of a flagship motel is that Don’s fantasy of a wife at work has, for some time, conflicted with Megan’s desire for a genuine career. While he does not expect her to tell him “You’re my king,” Don craves her proximity as though she were his talisman--a living, breathing version of the good luck fetish that Peggy sees in the violet candies Don gave her before a winning pitch. When Megan calls Don “master” and reproaches him for making his every wish her command, she brings to mind the very archetype of 60s fantasy wives. “Far Away Places” thus leaves us wondering if Megan can make Don happy while freeing herself from the day-glo decanter he expects her to enter on demand. Does their relationship represent the enduring “love” that may be a real “cure for neuroses”? Or will some future episode find them alone in the truth together?

In making Don’s story a Study in Orange, Mad Men builds a not-so-subtle bridge between the kind of psychedelia for which one needs an actual sugar cube, and the dreams and illusions that come to us courtesy of an emotional world. At some level we know that Don’s boorishness and foolery are all about guarding the fleeting happiness Roger has already lost. Like his daughter Sally, this forty-year old man does not want his “vacation to end.”

But the episode is not only a test case for psychoanalysis and psychotropia. As we have said many times on Kritik, Mad Men has never truly been about the early 60s. The show’s first three seasons told a story in which the pre-counterculture 60s became a powerful metaphor for the post-counterculture era of today. Viewers have always known that those 1960s would come sooner or later; that even Mad Men's milieu of white middle-class privilege would eventually feel their impact. In this sense, “Far Away Places” is to some degree about the sublimation of a culture, not an individual psyche. That is to say, by lining up the drug culture of “turning on” and “tuning in” with the psychedelic kitsch of a world in which even state troopers wear ultra-violet accessories, Mad Men is leaping ahead to the story that Thomas Frank tells in TheConquest of Cool. This is the story of how 60s counterculture, for all its rebellious promise, was not only co-opted but co-opted precisely by hipster ad men (including quasi-outsider Jews like Mad Men’s new copywriter “from Mars”). As advertisers fell over themselves to market the same old products to youth-oriented consumers, the counterculture, like love, become another way of selling nylons.

Or so says Thomas Frank. And perhaps also Mad Men. Toward the end of “Far Away Places” Don and Megan occupy the same position as Roger and Jane—only the camera leaves them before making any grand gesture of ascent. Megan says, “Every time we fight it just diminishes us a little bit.” When she gets up and tells him they have to go to work, they do. (Whereupon Bert’s call for a moratorium on the “love leave” may be all to the good and Roger, the only happy man in the episode, gets the last word).

But I prefer to end at the beginning with Peggy’s story: a “meanwhile” cordoned off from the rest by being told first. Peggy celebrates the defeat of failing with Heinz by taking herself to the movies: not The Naked Prey but Born Free, another 1966 film, but one more suitably centered on the return to the wild of a hitherto domesticated lioness. If this feels too neat, who knows exactly what Peggy is thinking when she makes friends at the movies. (I won't tell if you don't.) Peggy’s effort to be Don (playing his game of browbeating the client) doesn’t work because the “little girl” Don has running his office can’t embody what Don does when he pulls off that kind of stunt (see, for example, “The Hobo Code” Season 1, Episode 8, in which Don turns the act of pressuring a client into a full-blown sadomasochistic affair).

It is a lesson learned for Peggy who, while she hasn’t yet mastered the difficult art of being a woman in a world made by and for men, has at least no special compulsion to repeat her mistakes. Abe, we hope, will stop congratulating himself for not being a “pig” or Peggy will, perhaps, fly solo again. If the counterculture comes to mean something at all for Mad Men, one suspects that she will be on its front lines.

At any rate, that genie is out of the bottle.

"A Study in Orange"

Written by Lauren M. E. Goodlad (English/Unit for Criticism)

The title of Mad Men’s sixth episode this season, “Far Away Places,” echoes the 1948 Bing Crosby classic. But insofar as it leads viewers to anticipate the kind of glamorous business trip Don took with Betty in “Souvenir” (Season 3, Episode 8), the song’s yearning for real-life encounters with foreign lands is a feint. Although the episode explores far-off places of sorts, the journeys it takes in this rather complicated segment of Mad Men are more psychic and cultural than geographic. “Far Away Places” does not embark on real trips to Rome, or China, or Spain--though it does take us tripping. And in what has become a veritable leitmotif for Season 5, its most memorable tableaux are illusions.

Last week the show put us squarely in male fantasy terrain when Pete, hard at work with an obliging call girl, chose “You’re my king” over other equally tawdry clichés. Episode 6 opens with Abe’s suggesting that Peggy, nervous about her presentation for Heinz, join him at a showing of The Naked Prey. “You're gonna resist the chance to see Cornel Wilde naked?” he asks. Reviewing the movie in 1967, Roger Ebert called The Naked Prey the kind of “pure fantasy” in which an urbane white man, “set loose naked in the jungle,” discovers to his delight that he can “outrun half a dozen hand-picked African warriors.” Poor Abe. He has taken up Kinsey’s mantle of a white man engaged by the aspirations of the 60s with more humility than the often pompous Paul. Abe is clearly frustrated by Peggy’s distracted focus on work. But does he really want to see this movie?

In a post on “Tomorrowland,” last season’s finale, Rob Rushing and I wrote that Don’s unpremeditated proposal during a trip to California signaled a kind of repetition compulsion. In works like his famous essay on the “pleasure principle,” Sigmund Freud contemplated the strange human compulsion to repeat disturbing experiences so as to create the illusion of mastery. Don’s sudden decision to marry his secretary, Rob and I noted, was marked as repetitious first by Roger (who applauded Don’s following in his own footsteps) and then by Joan who mused, “It happens all the time.” Viewers who had warmed to the maturity of Dr. Faye Miller rolled their eyes as Don tethered himself to yet another gorgeous projection of the idealized mother he never had. Would Megan turn out to be a crafty “actress” who had played her boss?

As yet, the answer seems to be no. Instead of a Don/Roger dyad, Season 5 has focused on aligning Pete Campbell with the Don of yore. As Eleanor Courtemanche noted in her great post on last week’s episode, Pete has become the star of a suburban saga: an unhappy commuter with all of Don’s former wonderlust and little of his charm. By contrast, Megan, whose supposed love of children has vanished without a trace, is hardly eager to make babies in “the country.” In fact, unlike consummate trophy wife Jane Sterling, Megan is genuinely invested in work. More like Ken and Cynthia than Roger and Jane, the New Drapers could relate to one another as fellow professionals as well as husband and wife. Could, that is, if Don truly considered Megan a colleague like Peggy. But does he?

The question is part of the sustained meditation on upper-middle-class life which the season has so far dwelled on. Upping that ante, “Far Away Places” experiments with narrative techniques for depicting what the anthropologist Benedict Anderson calls simultaneity—the way that multiplot novels (and now serial television) engage modern time by creating “a complex gloss on meanwhile.” Juxtaposing three different couples—the Sterling/Draper doublet and the unmarried pair of Peggy and Abe-- the episode shows each twosome occupying the same slice of time. In a structure that could be called “Todayland,” time is rehearsed through the device of two literal “meanwhiles” to give us three different versions of the same roughly 24-hour period. The first is a scene of Don calling the office that only makes sense when we see it from his, not Peggy’s, perspective; the repetition of a second scene in which Don tells his secretary that he is away through the weekend, signals the shift from Sterling to Draper versions of the day.

Of course, Roger’s original plan was a different kind of pairing. On the morning of Peggy’s Heinz presentation, he proposes the kind of “completely debauched...‘fact-finding’ boondoggle” which (as Don reminds him) once landed him in the hospital after playing with twins (“Long Weekend,” Season 2, Episode 10). Entreating Don to join him on a road trip to Plattsburgh—home of the Howard Johnson’s “flagship”—Roger imagines a decadent escapade for “a couple of rich, handsome perverts.” But Don, who as Bert says is still on “love leave,” has a different idea of “playing hooky”--not an upstate hook-up but a Long Weekend with his wife. He leaves Roger both mocking and pining for his partner’s uxorious passion.

As Roger then rendezvouses with his own Mrs. in a marriage long past the honeymoon stage, he braces himself for dinner with her “snooty friends”—an evening that turns out to include existential philosophy, psychoanalysis, and LSD. Shaping Mad Men’s perspective on the budding trend for “turning on” and “tuning in,” Jane looks more like aStar Trek Goddess from Planet Up-Do than a hippychick at a Human Be-in. (All of these references are slightly ahead of the show’s current date, signaling, perhaps, that time is speeding up pace the teenager in Pete’s class in last week’s episode). At dinner, Jane’s shrink raises the compulsion to repeat: “I have patients who spend years reasoning out their motivation for a mistake and when they find it out they think they’ve found the truth.” Yet, they “go and make the same mistake.” As Rob and I noted, this same repetition compulsion underlies advertising’s hidden persuasion. By offering us empty illusions of having our cake and eating it too (like the ludicrous idea that eating beans makes us “included”), advertising invites us to hunker down with our neuroses.

Still, dropping acid turns out to have a bigger impact on the Sterlings than any canned commodity could. After first writing off Dr. Leary’s invention as another boring “product,” Roger disregards his host’s advice, “Don’t look in the mirror.” The result is a series of hallucinations which culminates in Don’s ordering him to go to his wife “because she wants to be alone in the truth with you.” Having earlier received a kind of message in a bottle—“I’m Roger Sterling…PLEASE HELP ME”—Roger is ready to face the music even if “the truth” and “the good” are not the same thing. As they lie on the floor, gazing up into space, Mad Men captures the Sterlings’ truthiness through a languorous crane shot. When they wake up the next morning, we worry for a moment that the acid was talking, not Jane herself--until she concludes that “It’s going to be very expensive.” Free at last (in an episode in which Joan, tellingly, makes no appearance), Roger is more than ready to embrace another costly divorce. If he is no better than the man who left Mona in Season 2, neither is he very much worse.

"Meanwhile," the Sterlings’ denouement coincides with a conjugal road trip that has Don almost panting for the excitement he felt at Disneyland. When Megan worries about Peggy and Heinz, Don cajoles, “Remember California?” When she continues to demur, Don pulls rank: “I’m the boss. I’m ordering you” he says with a poke. Always ready to have his cake and eat it too, Don anticipates a “love leave” with a little labor on the side. But just as Peggy frustrated Abe with her focus on work, so Megan resists Don’s vacation vibe. When she expresses her guilty sense of letting down coworkers, Don speaks to her straight from the phallus: “There has to be some advantage to being my wife.”

The road trip in other words, is saturated with signals of impending failure—my favorite of which is the way it harks back to the fabulous trip to Rome in “Souvenir”, including Don’s buying actual souvenirs for his kids. When Don says to Megan, “I got something for you” and then holds up a plastic back scratcher, can anyone miss how the man who took his first wife to the Hilton in Rome now expects his new wife to feel the magic of a HoJo’s in Plattsburgh? (The contrast between Conrad Hilton and Dale Vanderwort is almost too cruel to emphasize.) Too late Megan’s mother reminds Don that his wife is allergic to gold alloy.

Vanderwort’s desire to roll out the “orange carpet” as muzak fills the air opens a scene that would be a surreal Study in Orange were Don himself not so tragically impervious to the irony. It is as though Don is reliving a childhood memory that neither we nor Megan can see (just as Jane can’t see Roger’s hallucination of a fondly remembered world series). When Don tells Megan with the straightest of faces, “The colors are bright and cheerful, the kids have candy, full bar for Mom and Dad: would you say it’s a delightful destination?”, it is momentarily unclear whether Don has simply collapsed the boundary of work and play or whether it isn’t after all him, not Roger, who’s been drinking the electric kool-aid—orange of course. "It's not a destination," Megan tells him "it's on the way to someplace."

By now, we can see it coming: “You like to work, but I can’t like to work,” Megan reasonably complains. If he has so far been lightly insufferable that is nothing to how Don behaves when told he’s been inconsiderate. And what perfect timing! The giant serving of orange sherbet he insisted on ordering arrives just in time to become the edible emblem for every infantile wish he has sunk into this bad trip. Predictably, Megan (despite her chic coral dress) does not like orange sherbet which tastes fake, “like perfume.” The waitress, (knowing the actual value of a Ho Jo’s) takes it in perfect stride. But as Megan orders chocolate, Don visibly experiences himself as a rejected flavor of frozen dessert, accusing her of embarrassing him. When Megan shows us that she really is a good actress, shoveling sherbet in her mouth in a performance that unnervingly recalls the fake orgasm scene in When Harry Met Sally we know that it is far too late to settle on another flavor. (This would be true even if Megan had not stumbled over the dreaded “m”-word asking Don about his [dead, prostitute] mother.)

What is clear long before the spat in the tangerine glow of a flagship motel is that Don’s fantasy of a wife at work has, for some time, conflicted with Megan’s desire for a genuine career. While he does not expect her to tell him “You’re my king,” Don craves her proximity as though she were his talisman--a living, breathing version of the good luck fetish that Peggy sees in the violet candies Don gave her before a winning pitch. When Megan calls Don “master” and reproaches him for making his every wish her command, she brings to mind the very archetype of 60s fantasy wives. “Far Away Places” thus leaves us wondering if Megan can make Don happy while freeing herself from the day-glo decanter he expects her to enter on demand. Does their relationship represent the enduring “love” that may be a real “cure for neuroses”? Or will some future episode find them alone in the truth together?

In making Don’s story a Study in Orange, Mad Men builds a not-so-subtle bridge between the kind of psychedelia for which one needs an actual sugar cube, and the dreams and illusions that come to us courtesy of an emotional world. At some level we know that Don’s boorishness and foolery are all about guarding the fleeting happiness Roger has already lost. Like his daughter Sally, this forty-year old man does not want his “vacation to end.”

But the episode is not only a test case for psychoanalysis and psychotropia. As we have said many times on Kritik, Mad Men has never truly been about the early 60s. The show’s first three seasons told a story in which the pre-counterculture 60s became a powerful metaphor for the post-counterculture era of today. Viewers have always known that those 1960s would come sooner or later; that even Mad Men's milieu of white middle-class privilege would eventually feel their impact. In this sense, “Far Away Places” is to some degree about the sublimation of a culture, not an individual psyche. That is to say, by lining up the drug culture of “turning on” and “tuning in” with the psychedelic kitsch of a world in which even state troopers wear ultra-violet accessories, Mad Men is leaping ahead to the story that Thomas Frank tells in TheConquest of Cool. This is the story of how 60s counterculture, for all its rebellious promise, was not only co-opted but co-opted precisely by hipster ad men (including quasi-outsider Jews like Mad Men’s new copywriter “from Mars”). As advertisers fell over themselves to market the same old products to youth-oriented consumers, the counterculture, like love, become another way of selling nylons.

Or so says Thomas Frank. And perhaps also Mad Men. Toward the end of “Far Away Places” Don and Megan occupy the same position as Roger and Jane—only the camera leaves them before making any grand gesture of ascent. Megan says, “Every time we fight it just diminishes us a little bit.” When she gets up and tells him they have to go to work, they do. (Whereupon Bert’s call for a moratorium on the “love leave” may be all to the good and Roger, the only happy man in the episode, gets the last word).

But I prefer to end at the beginning with Peggy’s story: a “meanwhile” cordoned off from the rest by being told first. Peggy celebrates the defeat of failing with Heinz by taking herself to the movies: not The Naked Prey but Born Free, another 1966 film, but one more suitably centered on the return to the wild of a hitherto domesticated lioness. If this feels too neat, who knows exactly what Peggy is thinking when she makes friends at the movies. (I won't tell if you don't.) Peggy’s effort to be Don (playing his game of browbeating the client) doesn’t work because the “little girl” Don has running his office can’t embody what Don does when he pulls off that kind of stunt (see, for example, “The Hobo Code” Season 1, Episode 8, in which Don turns the act of pressuring a client into a full-blown sadomasochistic affair).

It is a lesson learned for Peggy who, while she hasn’t yet mastered the difficult art of being a woman in a world made by and for men, has at least no special compulsion to repeat her mistakes. Abe, we hope, will stop congratulating himself for not being a “pig” or Peggy will, perhaps, fly solo again. If the counterculture comes to mean something at all for Mad Men, one suspects that she will be on its front lines.

At any rate, that genie is out of the bottle.