[The seventh in the Unit for Criticism's multi-authored series of posts on Season 5 of AMC's Mad Men, posted prior to the publication of MAD MEN, MAD WORLD: Sex, Politics, Style, and the 1960s(Duke University Press) Eds. Lauren M. E. Goodlad, Lilya Kaganovsky and Robert A. Rushing]

"It Is Being"

Written by Jeremy Varon (The New School)

By the time Pete Campbell beds the forlorn wife of a philandering suburban fellow traveler, an old-school Mad Men slime-fest seems full on. Explaining his entitlement to “a side dish in the city” — while playing Pete for a life insurance sale — the train mate Howard Dawes had restated the delusional macho writ of Seasons 1-3 which gave husbands license and left their wives miserable: “She’s happy because I provide for her.” Pete, taking the pitch too well, parlays — as per the vintage Don Draper — ennui into conquest, complete with post-coital, existential pillow talk and handsomely mussed hair.

But there’s a twist. Beth Dawes, after all, had initiated the vengeful seduction, confessing “I used to be like this . . . reckless.” (No prudish Betty, she). As Meg’s mysterious night out snakes through the Campbell plotline, we appear to have graduated into a world in which women at least give as good as they get. Call it progress, the 60s on the slow march.

The crude parallelism of men and women behaving badly, however, is quickly suffused in a complex series of doublings or chiasmi; these permit the episode far grander commentary on the changing station of women, change in individuals’ lives, and, in a newish theme for Mad Men, how change and death comingle. Change itself is of course the arch-theme of the entire season, imposed by the times and begged for by countless “What next for the Mad Men?” pre-season commentaries. Each of Season 5’s installments can be read in terms of the extent to which the Mad World allows in, keeps at bay, or allows itself to be shaken by everything famously rattling walls in 1966, from the Civil Rights Movement, to feminism, the Vietnam War, and LSD.

Some issues, like race, enter only fleetingly (so far), leaving as quickly as purloined bonus pay from a white girl’s purse. (As if providing meta-commentary on the show’s increasingly untenable banishing of nearly all subaltern identities and their struggles, Pete says of urban hobos, “I guess we’re supposed to get used to not seeing them,” to which Beth replies, “Yes, that’s exactly what happens.”) Other themes, such as rock ‘n roll as the soundtrack of a new generation, or feminism’s emergence through a widening circle of Mad Women, have greater staying power.

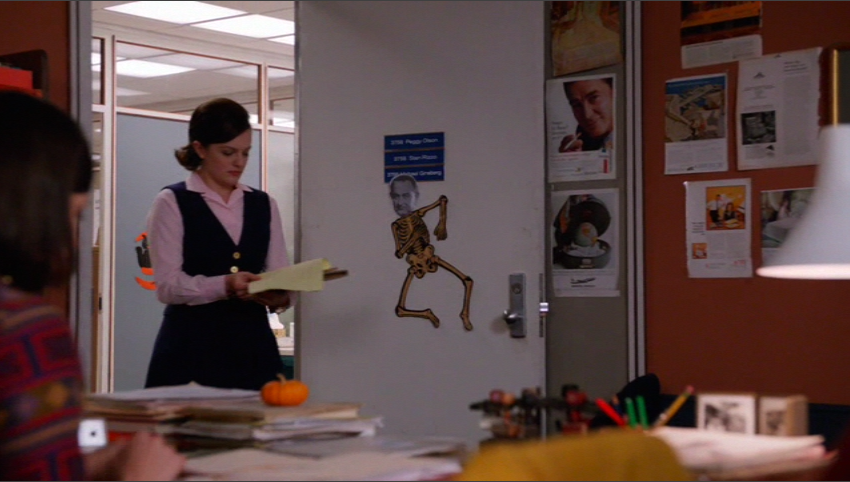

But mostly, as Kritik’s contributors have noted (and occasionally grumbled over), “history” registers only obliquely in allusive temporal markers and the slowly shifting grammar of the characters’ lives. (Note the Lyndon Johnson head cheekily affixed to a skeleton on the copywriters’ door, while news of Vietnam bleeds through the radio.) But here too Mad Men avoids the temptations of convention. Rather than give us so many Bildung narratives — the bounded journeys of Peggy, Don, Joan, et al. as allegories of social transformation — the show crafts most characters as reflections, or imitations, or repudiations of one another. By this means, identity is presented as fundamentally intersubjective, transferential, and based in repetition: the self as (an)other.

Struggling to make their way, the characters face the perpetual threat of deeper estrangement by collapsing into someone else or being confronted by avatars of their prior selves. In this way, apparent “authenticity” is always called into question, as is the durability of apparent change at the micro- and macro-levels. By extension, the show is able to stage structured ambivalence that resists easy synthesis or closure, thereby mirroring the open-endedness and internal negativity of both history and subjectivity. Though the Beatles increasingly dominate the show’s musical sensibility, a roughly contemporaneous line from Dylan’s "Baby Blue" captures one version of this haunting: “The vagabond who’s wrapping at your door / is standing in the clothes that you once wore.”

Long simmering in Season 5’s plotlines, character-doubling boils over in Episode 8, "Lady Lazarus." Pete is now plainly becoming the old Don, while scheming to be Roger. Meg, in her secretary-to-copywriter trajectory, at first mimics Peggy. Yet with her second emancipation, as Joan’s cynical take on Meg’s acting talents and resolve suggests, she risks reverting to Betty. Peggy, herself fearful in her liquor-swilling moments of becoming Don, literally stands in for Meg in an awkward husband-and-wife client pitch. And Don, always already doubled by virtue both of his Draper-Whitman identities and uncommonly extreme devil and angel sides, is drawn again to being a better man.

The great irony is that this exquisite confusion comes in an installment devoted to the wholesome pursuit of being yourself and following your dream. Meg leads the charge in what is the episode’s ostensible crisis: her fraught desire to leave the agency to revive a stalled acting career and her even greater fear of telling Don. Her dilemma provides occasion for one of the show’s great stagings of personal-as-political solidarity among women, held literally in the ladies' room — that semi-private sanctum of female affirmation. Peggy, with tough-love generosity, encourages Meg to marshal the courage both to reject a world she had herself struggled so hard to enter and to stand up to Don.

In social terms, Meg’s angst marks new horizons for women. Betty, the erstwhile model, had answered the vagaries of the feminine mystique by trading for a more reliable benefactor and a still lonelier suburban castle. Meg, just two years later (but several years younger), resists the elevated trap of an unfulfilling profession by following her heart path. Time will tell if Peggy is right to see Meg as “one of those girls who can do anything” or if Joan is fair in reducing her to “the kind of girl Don marries.”

The crisis actually registers most profoundly in Don, now pressured to take his kinder and gentler self perhaps farther than he ever thought possible or necessary. He has already upgraded and modernized his existence. Gone is his possession of a cloistered supermodel-as-suburban-homemaker, who summons mostly his contempt. In Meg, he has an equally stunning but talented and ambitious professional urban woman whom he can decently love. But it remains a paternalistic, even imperious fantasy of control, now wrought by transparency and de facto surveillance, not deception. Meg is omnipresent to him as, at once, his partner, lover, soul mate, employee, colleague, co-creator, and occasional homemaker. But for Meg, to live this life in its professional (and not domestic) aspect is to die little deaths, as her dream is deferred to oblivion. Originating in modest subterfuge, her escape quickly ripens into game-changing, confessional honesty with Don and a new lease on life. Lady Lazarus, Megan has raised herself from the dead.

Don responds to her news with reasonableness, sympathy, and stoic benevolence, resolving in twin, cathartic realizations: first, that he is not wholly responsible for, or equivalent to, her happiness (something generations of husbands still learn); second, that her happiness, predicated on a measure of autonomy, need not come at the expense of his own, which was likely never sustainable in his new fantasy of perpetual Disneyland. In a rare portrait of earnest satisfaction, Don’s lips slowly curl toward a smile as he holds his freshly emancipated wife in his genuinely loving arms. Now synched to Megan’s wishes, Don proves himself far more “with it” than his bumbling inability to recognize the Beatles’ “sound” would suggest.

Don’s acceptance of his circumstances and her need for autonomy, however, does not rest lightly, summoning new images of death. Clearly shaken the next day, he escorts Meg to the elevator for her farewell luncheon with all the bittersweet affect of a father dropping off his daughter to her first year of college, or walking her to the marriage altar. That ambivalence becomes a morbid swoon as he peers down the empty shaft of the neighboring elevator he had nearly stepped into. Two readings are suggested by this jarring, did-that-really-happen scene, which together preserve Don as an insoluble schism. In one, letting go and giving himself over to change feels to him like its own little death, over which he can triumph. He stares at — and stares down — the abyss of contingency and fragile hope as death, and comes through it okay. His redemption is to survive that panic, in tact, the better man for standing back to let others have and make their way.

In another, sharply contrary take on the scene, Don peers at an image of his own persisting emptiness, no matter the increasing richness of his life. While Megan descends to begin her journey toward Broadway’s bright lights, Don beholds from his floating perch the absence of any true dream of his own, or even a desiring self to propel a dream that may walk the earth. He thus stands at the literal precipice of the existential free-fall and dreamy nihilism that the unchanging, opening credits suggest is his chronic condition. Quickly seeking refuge in the welcoming forest of office liquor, he finds comfort but no true peace. (I thank, I should say, my astute wife Alice Varon for this “second reading,” from which the core structure of this entire essay derives.)

In a final, somewhat different doubling, the show concludes by restaging this dyadic drama Beatles-style. Don is now ripe to commune with the sound of a new generation, having come by his initiation honestly. Left alone by Meg with Revolver, Don hears first the epic track “Tomorrow Never Knows.” Lennon’s (and George Martin’s) LSD-infused masterpiece signals a new peak in the psychedelic revolution, now going mainstream. With lyrics drawing from Timothy Leary’s adaptation of The Tibetan Book of the Dead, the song bids the still-shaken Don, “Turn off your mind, relax, and float downstream / It is not dying / This is not dying / Lay down all thoughts, surrender to the void / It is shining.” Doing as instructed, Don gives himself over to Tomorrow Never Knows and the serendipities of chance. However scary, it is not dying. So edified, and coming to, he then drifts off to bed, ready to face the next day awakened. Roger that!

In another interpretive possibility, his apparent reverie is more bad trip than revelation. While he lingers in collapse, we see an image of Megan, lying still as death in her acting class, but oddly grounded in her welcoming void. In between, there is an image of Pete and Beth’s desperate, star-crossed affection, redolent of the aching impossibility of the Roger-Joan coupling of the Mad Men of yore. Don turns off the record with an agitated scratch, and exits the forbidding void of his exquisitely decorated apartment to rest up for another day in an equally empty life.

N.B. The Editors of this project and Jeremy Varon wish to take this opportunity to thank the director of this episode, Phil Abraham, for his contribution to our forthcoming book, Mad Men, Mad World.

"It Is Being"

Written by Jeremy Varon (The New School)

By the time Pete Campbell beds the forlorn wife of a philandering suburban fellow traveler, an old-school Mad Men slime-fest seems full on. Explaining his entitlement to “a side dish in the city” — while playing Pete for a life insurance sale — the train mate Howard Dawes had restated the delusional macho writ of Seasons 1-3 which gave husbands license and left their wives miserable: “She’s happy because I provide for her.” Pete, taking the pitch too well, parlays — as per the vintage Don Draper — ennui into conquest, complete with post-coital, existential pillow talk and handsomely mussed hair.

But there’s a twist. Beth Dawes, after all, had initiated the vengeful seduction, confessing “I used to be like this . . . reckless.” (No prudish Betty, she). As Meg’s mysterious night out snakes through the Campbell plotline, we appear to have graduated into a world in which women at least give as good as they get. Call it progress, the 60s on the slow march.

The crude parallelism of men and women behaving badly, however, is quickly suffused in a complex series of doublings or chiasmi; these permit the episode far grander commentary on the changing station of women, change in individuals’ lives, and, in a newish theme for Mad Men, how change and death comingle. Change itself is of course the arch-theme of the entire season, imposed by the times and begged for by countless “What next for the Mad Men?” pre-season commentaries. Each of Season 5’s installments can be read in terms of the extent to which the Mad World allows in, keeps at bay, or allows itself to be shaken by everything famously rattling walls in 1966, from the Civil Rights Movement, to feminism, the Vietnam War, and LSD.

Some issues, like race, enter only fleetingly (so far), leaving as quickly as purloined bonus pay from a white girl’s purse. (As if providing meta-commentary on the show’s increasingly untenable banishing of nearly all subaltern identities and their struggles, Pete says of urban hobos, “I guess we’re supposed to get used to not seeing them,” to which Beth replies, “Yes, that’s exactly what happens.”) Other themes, such as rock ‘n roll as the soundtrack of a new generation, or feminism’s emergence through a widening circle of Mad Women, have greater staying power.

But mostly, as Kritik’s contributors have noted (and occasionally grumbled over), “history” registers only obliquely in allusive temporal markers and the slowly shifting grammar of the characters’ lives. (Note the Lyndon Johnson head cheekily affixed to a skeleton on the copywriters’ door, while news of Vietnam bleeds through the radio.) But here too Mad Men avoids the temptations of convention. Rather than give us so many Bildung narratives — the bounded journeys of Peggy, Don, Joan, et al. as allegories of social transformation — the show crafts most characters as reflections, or imitations, or repudiations of one another. By this means, identity is presented as fundamentally intersubjective, transferential, and based in repetition: the self as (an)other.

Struggling to make their way, the characters face the perpetual threat of deeper estrangement by collapsing into someone else or being confronted by avatars of their prior selves. In this way, apparent “authenticity” is always called into question, as is the durability of apparent change at the micro- and macro-levels. By extension, the show is able to stage structured ambivalence that resists easy synthesis or closure, thereby mirroring the open-endedness and internal negativity of both history and subjectivity. Though the Beatles increasingly dominate the show’s musical sensibility, a roughly contemporaneous line from Dylan’s "Baby Blue" captures one version of this haunting: “The vagabond who’s wrapping at your door / is standing in the clothes that you once wore.”

Long simmering in Season 5’s plotlines, character-doubling boils over in Episode 8, "Lady Lazarus." Pete is now plainly becoming the old Don, while scheming to be Roger. Meg, in her secretary-to-copywriter trajectory, at first mimics Peggy. Yet with her second emancipation, as Joan’s cynical take on Meg’s acting talents and resolve suggests, she risks reverting to Betty. Peggy, herself fearful in her liquor-swilling moments of becoming Don, literally stands in for Meg in an awkward husband-and-wife client pitch. And Don, always already doubled by virtue both of his Draper-Whitman identities and uncommonly extreme devil and angel sides, is drawn again to being a better man.

The great irony is that this exquisite confusion comes in an installment devoted to the wholesome pursuit of being yourself and following your dream. Meg leads the charge in what is the episode’s ostensible crisis: her fraught desire to leave the agency to revive a stalled acting career and her even greater fear of telling Don. Her dilemma provides occasion for one of the show’s great stagings of personal-as-political solidarity among women, held literally in the ladies' room — that semi-private sanctum of female affirmation. Peggy, with tough-love generosity, encourages Meg to marshal the courage both to reject a world she had herself struggled so hard to enter and to stand up to Don.

In social terms, Meg’s angst marks new horizons for women. Betty, the erstwhile model, had answered the vagaries of the feminine mystique by trading for a more reliable benefactor and a still lonelier suburban castle. Meg, just two years later (but several years younger), resists the elevated trap of an unfulfilling profession by following her heart path. Time will tell if Peggy is right to see Meg as “one of those girls who can do anything” or if Joan is fair in reducing her to “the kind of girl Don marries.”

The crisis actually registers most profoundly in Don, now pressured to take his kinder and gentler self perhaps farther than he ever thought possible or necessary. He has already upgraded and modernized his existence. Gone is his possession of a cloistered supermodel-as-suburban-homemaker, who summons mostly his contempt. In Meg, he has an equally stunning but talented and ambitious professional urban woman whom he can decently love. But it remains a paternalistic, even imperious fantasy of control, now wrought by transparency and de facto surveillance, not deception. Meg is omnipresent to him as, at once, his partner, lover, soul mate, employee, colleague, co-creator, and occasional homemaker. But for Meg, to live this life in its professional (and not domestic) aspect is to die little deaths, as her dream is deferred to oblivion. Originating in modest subterfuge, her escape quickly ripens into game-changing, confessional honesty with Don and a new lease on life. Lady Lazarus, Megan has raised herself from the dead.

Don responds to her news with reasonableness, sympathy, and stoic benevolence, resolving in twin, cathartic realizations: first, that he is not wholly responsible for, or equivalent to, her happiness (something generations of husbands still learn); second, that her happiness, predicated on a measure of autonomy, need not come at the expense of his own, which was likely never sustainable in his new fantasy of perpetual Disneyland. In a rare portrait of earnest satisfaction, Don’s lips slowly curl toward a smile as he holds his freshly emancipated wife in his genuinely loving arms. Now synched to Megan’s wishes, Don proves himself far more “with it” than his bumbling inability to recognize the Beatles’ “sound” would suggest.

Don’s acceptance of his circumstances and her need for autonomy, however, does not rest lightly, summoning new images of death. Clearly shaken the next day, he escorts Meg to the elevator for her farewell luncheon with all the bittersweet affect of a father dropping off his daughter to her first year of college, or walking her to the marriage altar. That ambivalence becomes a morbid swoon as he peers down the empty shaft of the neighboring elevator he had nearly stepped into. Two readings are suggested by this jarring, did-that-really-happen scene, which together preserve Don as an insoluble schism. In one, letting go and giving himself over to change feels to him like its own little death, over which he can triumph. He stares at — and stares down — the abyss of contingency and fragile hope as death, and comes through it okay. His redemption is to survive that panic, in tact, the better man for standing back to let others have and make their way.

In another, sharply contrary take on the scene, Don peers at an image of his own persisting emptiness, no matter the increasing richness of his life. While Megan descends to begin her journey toward Broadway’s bright lights, Don beholds from his floating perch the absence of any true dream of his own, or even a desiring self to propel a dream that may walk the earth. He thus stands at the literal precipice of the existential free-fall and dreamy nihilism that the unchanging, opening credits suggest is his chronic condition. Quickly seeking refuge in the welcoming forest of office liquor, he finds comfort but no true peace. (I thank, I should say, my astute wife Alice Varon for this “second reading,” from which the core structure of this entire essay derives.)

In a final, somewhat different doubling, the show concludes by restaging this dyadic drama Beatles-style. Don is now ripe to commune with the sound of a new generation, having come by his initiation honestly. Left alone by Meg with Revolver, Don hears first the epic track “Tomorrow Never Knows.” Lennon’s (and George Martin’s) LSD-infused masterpiece signals a new peak in the psychedelic revolution, now going mainstream. With lyrics drawing from Timothy Leary’s adaptation of The Tibetan Book of the Dead, the song bids the still-shaken Don, “Turn off your mind, relax, and float downstream / It is not dying / This is not dying / Lay down all thoughts, surrender to the void / It is shining.” Doing as instructed, Don gives himself over to Tomorrow Never Knows and the serendipities of chance. However scary, it is not dying. So edified, and coming to, he then drifts off to bed, ready to face the next day awakened. Roger that!

In another interpretive possibility, his apparent reverie is more bad trip than revelation. While he lingers in collapse, we see an image of Megan, lying still as death in her acting class, but oddly grounded in her welcoming void. In between, there is an image of Pete and Beth’s desperate, star-crossed affection, redolent of the aching impossibility of the Roger-Joan coupling of the Mad Men of yore. Don turns off the record with an agitated scratch, and exits the forbidding void of his exquisitely decorated apartment to rest up for another day in an equally empty life.

N.B. The Editors of this project and Jeremy Varon wish to take this opportunity to thank the director of this episode, Phil Abraham, for his contribution to our forthcoming book, Mad Men, Mad World.