[The eighth in the Unit for Criticism's multi-authored series of posts on Season 5 of AMC's Mad Men, in anticipation of publishing MAD MEN, MAD WORLD: Sex, Politics, Style, and the 1960s (Duke University Press) Eds. Lauren M. E. Goodlad, Lilya Kaganovsky and Robert A. Rushing]

“Ozymandias”

Written by Carl Lehnen (Graduate School of Library and Information Science)

In earlier seasons, we were told that the appeal of Mad Men lay in the vicarious thrill of watching others guiltlessly enjoy all of the pleasures—alcohol, cigarettes, and adultery—that the mores of our more enlightened and careful age denied us. Perhaps this is the kind of pleasure that Don has in mind when, attempting to recapture the old creative spark, he brainstorms a pitch for Sno Ball. His lurching free association, which recalls--even if it cannot match--last season’s cringe-worthy “Cure for the common breakfast,” leads him from “a snowball’s chance in hell” to the well-worn theme of forbidden pleasure: “Refreshing for the damned. Sno Ball is the sin that gets you into hell... sinfully delicious.” But even he recognizes the tiredness of the conceit, or at least the inappropriateness of such a theme for a children’s soft drink.

This episode asks us to think about pleasure in a different way—as something that must be carefully measured out, not consumed all at once.

The last time we saw Betty, she was relishing the second half of Sally’s ice cream sundae—a scene that, as Rob Rushing noted, underlined her immaturity and self-absorption. In this episode, however, Betty has joined Weight Watchers, and in the first scene we see her weighing cubes of cheese on a scale so that she won’t overrun her daily allotment of calories, and then sitting down to a meal that combines them with burnt toast and half a grapefruit.

This effort of self-discipline represents just one of the kinds of control that characters attempt to retake in this episode. Often it involves older characters who have watched their power get chipped away by upstarts: Bert and Roger try to get some business going without Pete’s involvement in order to prove that they still have a purpose at SCDP; Don sabotages Ginsberg’s superior Sno Ball pitch in order to prove that he can still be creative; and Betty shows that she still has plenty of secrets with the power to upset the new Draper household.

Early in this episode, Roger explains to Bert that competitive fishing isn’t about “man vs. fish,” but about “man vs. man… the weighing, the measuring” (although he does allow that he doesn’t “respect anything that rewards you for silence”). There is certainly plenty of weighing and measuring going on here. Betty weighs her food before weighing herself, then measures herself against Megan; Don measures himself against the new copywriter Ginsberg; and Bert and Roger’s plot to win an account with Manischewitz is yet another amusing skirmish in their ongoing feud with Pete Campbell. (According to at least one source, 1965 was the year when kosher foods such as Hebrew National hot dogs and Levy’s rye bread began to be marketed to gentile audiences).

In another scene, Megan helps her actress friend practice for a guest role on Dark Shadows, the 1960s supernatural soap opera. In this winking allusion, the episode makes a timely comment about its own soapiness while also distinguishing itself from the competition. (Perhaps unconvincingly, a spokesperson for Mad Men claimed on Monday that the opening of the film the previous Friday “was truly just a coincidence.”) We watch Megan’s friend play the part of a jealous lover (“What could that miserable schoolmarm offer him that I can’t? I’ll kill myself, I will!”), but Megan can’t help laughing (“Who is this woman? … She’s insane. She needs a drink.”), and in this episode most of the confrontations between rivals will take place in silence or through intermediaries.

Even from their compromised positions, the more senior characters generally show that they still have what it takes (if not to win, then at least to make a dent in the other guy)—but at a considerable cost to themselves. Roger does successfully win the account, but only by reaching, as so often this season, into his own wallet (“This is the most expensive dinner in history,” he tells Jane), and at the dinner itself he is romantically upstaged by the handsome young Manischewitz fils. Even Don, who takes the most direct route by simply leaving Ginsberg’s work in the cab and making a naked assertion of office seniority, seems very far from the creative exhilaration of pitching to Kodak or Lucky Strike. And Betty, in one of her most sympathetic and complicated appearances in years, is forced to confront the limitations of her own power and pleasure.

In his earlier post, Rushing asked what future Betty has in this show. Although “part of the essential iconography of Mad Men,” she has generally been peripheral to its office intrigues, and since her divorce from Don she has had little do except behave badly within her own sphere. Here, though, her plot line comments on the others without becoming a mere echo of them.

In keeping with the show’s increasingly urban focus and its representation of the suburbs as a kind of exile, Betty and Henry find themselves ill at ease in the city. When Betty lets herself wander around Don and Megan’s apartment with an appraising eye, she self-consciously checks her appearance in a mirror and clumsily bumps into a lamp, as if she is literally too large for their chic apartment. When she walks to the window to check out the view, she is surprised by the sight of Megan getting dressed across the patio. As the new Mrs. Draper, Megan is the object of highly ambivalent feelings on Betty’s part. She is young, beautiful, and enjoys the love that Betty wanted but which Don was unable or unwilling to give her. She represents a kind of previous self for Betty, but also a mirror image. She has what Betty wants, but she also occupies a position that Betty notably gave up. And even though we can see the pain it causes Betty to be reminded of her insecurities, the fact that she continues to look suggests a kind of pleasure. (And why exactly is that whale smiling like some kind of aquatic Saint Teresa?)

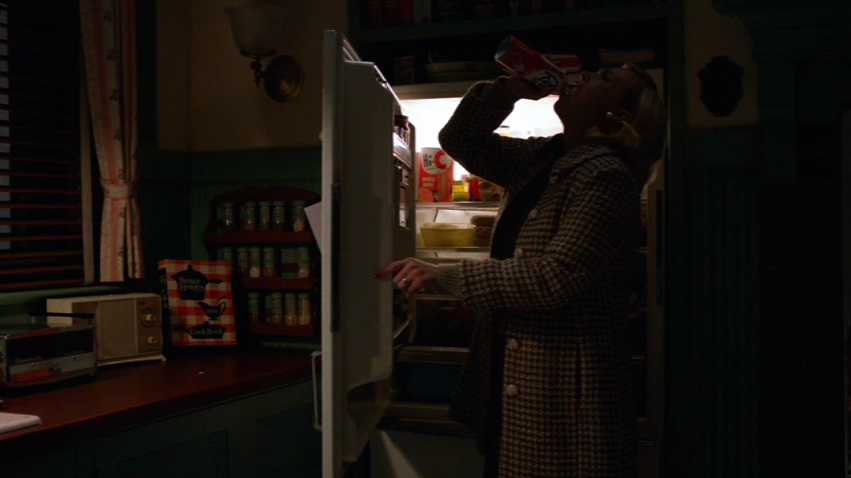

When we see Betty again, she is compensating for her surreptitious glimpse of Megan by surreptitiously filling up her mouth with Reddi-Whip, a pleasure that is emphatically substitutive, and, although tempting, far from irresistible. That this scene comes immediately after Don’s “sinfully delicious” line only underlines its emptiness. (In “Lady Lazarus,” Don unconvincingly explains that Cool Whip is not “fake whipped cream,” but a “nondairy whipped topping” that “comes frozen.” Don and Megan then act out a proposed commercial in which they play a happy couple, with Megan urging the dessert on her husband, an exchange that itself recalls the incident in “Faraway Places” in which Don and Megan fight over orange sherbet-as-symbol-of-faked-pleasure.)

Betty struggles in this episode to assert control over her body and her emotions. She uses Weight Watchers as a kind of group-therapy-lite where she can share highly abridged stories and receive support. In another scene of eating, she catches Henry sneaking a pork chop, but instead of getting angry or upset, as the Betty of last season might have done, she helps him and listens sympathetically to his story of political miscalculation. Henry worries that he’s “bet on the wrong horse” and “jumped ship for nothing,” a concern that we could imagine Betty sharing: did she make the right decision to leave Don for Henry? But she reaffirms her commitment, telling him that “I’m here to help you, as you’re here to help me.” Betty is self-aware and generous here, but studiedly, as if it’s a new behavior she’s learned about in class but never really tried out before.

That she slips up again when she comes across Don’s genuinely sweet note to Megan is understandable, since it represents exactly the kind of honest love that he withheld from her. Setting her jaw against her own misgivings, she plants just the seed that she knows will feed Sally’s pre-adolescent resentment and enrage Don. (“I don’t know why Megan didn’t tell you,” she says after eating a celery stick.)

These plots to undermine rivals often have a way of temporarily empowering the younger characters that are enlisted to do the work of their elders: Sally gets to confront Megan with her new secret, Jane gets the promise of a new life in a new apartment, and Ginsberg prematurely declaims “Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!” The quotation of Shelley’s poem is especially apropos, both to the episode and to the series in general (I’m thinking especially of debates about Mad Men’s representation of the 1960s), since it presents history as a sublime ruin rather than as progress or the endurance of any particular human creation.

Of these, Sally’s story is perhaps the most interesting. At the beginning of the episode, we see Megan teaching her to fake tears to get what she wants. Megan might have thought she was teaching Sally useful skills of manipulation, but Sally has learned from more seasoned operators, and painfully one-ups her with accusations of betrayal. When she realizes how her mother was trying to use her, Sally turns it back on Betty, knowing that the most effective way to hurt her is to pretend that nothing is wrong. Sally probably thinks that she is merely doing her best to hold her own ground against the deception and turpitude of the old, but her behavior says just as much about the ignorant ruthlessness of the young.

When, as so often in this show, characters find their victories turn out to be hollow, what is the solution? In the final Thanksgiving scene, Betty says “I’m thankful I have everything I want, and no one has anything better.” Can we hear this as a step down the path of maturity, an attempt to give up desiring what she can’t have by focusing on Weight Watchers’ brand of self-improvement? Or is it an Ozymandias-like display of false pride, a retreat into infantile self-absorption no better than Bobby’s appreciation for having two really big houses? In this case, the look on Betty’s face as she tastes her pathetically measured out turkey dinner says more than I can: the ecstasy of tasting a deferred pleasure and despair at its limitedness, followed by something like acceptance.

“Ozymandias”

Written by Carl Lehnen (Graduate School of Library and Information Science)

In earlier seasons, we were told that the appeal of Mad Men lay in the vicarious thrill of watching others guiltlessly enjoy all of the pleasures—alcohol, cigarettes, and adultery—that the mores of our more enlightened and careful age denied us. Perhaps this is the kind of pleasure that Don has in mind when, attempting to recapture the old creative spark, he brainstorms a pitch for Sno Ball. His lurching free association, which recalls--even if it cannot match--last season’s cringe-worthy “Cure for the common breakfast,” leads him from “a snowball’s chance in hell” to the well-worn theme of forbidden pleasure: “Refreshing for the damned. Sno Ball is the sin that gets you into hell... sinfully delicious.” But even he recognizes the tiredness of the conceit, or at least the inappropriateness of such a theme for a children’s soft drink.

This episode asks us to think about pleasure in a different way—as something that must be carefully measured out, not consumed all at once.

The last time we saw Betty, she was relishing the second half of Sally’s ice cream sundae—a scene that, as Rob Rushing noted, underlined her immaturity and self-absorption. In this episode, however, Betty has joined Weight Watchers, and in the first scene we see her weighing cubes of cheese on a scale so that she won’t overrun her daily allotment of calories, and then sitting down to a meal that combines them with burnt toast and half a grapefruit.

This effort of self-discipline represents just one of the kinds of control that characters attempt to retake in this episode. Often it involves older characters who have watched their power get chipped away by upstarts: Bert and Roger try to get some business going without Pete’s involvement in order to prove that they still have a purpose at SCDP; Don sabotages Ginsberg’s superior Sno Ball pitch in order to prove that he can still be creative; and Betty shows that she still has plenty of secrets with the power to upset the new Draper household.

Early in this episode, Roger explains to Bert that competitive fishing isn’t about “man vs. fish,” but about “man vs. man… the weighing, the measuring” (although he does allow that he doesn’t “respect anything that rewards you for silence”). There is certainly plenty of weighing and measuring going on here. Betty weighs her food before weighing herself, then measures herself against Megan; Don measures himself against the new copywriter Ginsberg; and Bert and Roger’s plot to win an account with Manischewitz is yet another amusing skirmish in their ongoing feud with Pete Campbell. (According to at least one source, 1965 was the year when kosher foods such as Hebrew National hot dogs and Levy’s rye bread began to be marketed to gentile audiences).

In another scene, Megan helps her actress friend practice for a guest role on Dark Shadows, the 1960s supernatural soap opera. In this winking allusion, the episode makes a timely comment about its own soapiness while also distinguishing itself from the competition. (Perhaps unconvincingly, a spokesperson for Mad Men claimed on Monday that the opening of the film the previous Friday “was truly just a coincidence.”) We watch Megan’s friend play the part of a jealous lover (“What could that miserable schoolmarm offer him that I can’t? I’ll kill myself, I will!”), but Megan can’t help laughing (“Who is this woman? … She’s insane. She needs a drink.”), and in this episode most of the confrontations between rivals will take place in silence or through intermediaries.

Even from their compromised positions, the more senior characters generally show that they still have what it takes (if not to win, then at least to make a dent in the other guy)—but at a considerable cost to themselves. Roger does successfully win the account, but only by reaching, as so often this season, into his own wallet (“This is the most expensive dinner in history,” he tells Jane), and at the dinner itself he is romantically upstaged by the handsome young Manischewitz fils. Even Don, who takes the most direct route by simply leaving Ginsberg’s work in the cab and making a naked assertion of office seniority, seems very far from the creative exhilaration of pitching to Kodak or Lucky Strike. And Betty, in one of her most sympathetic and complicated appearances in years, is forced to confront the limitations of her own power and pleasure.

In his earlier post, Rushing asked what future Betty has in this show. Although “part of the essential iconography of Mad Men,” she has generally been peripheral to its office intrigues, and since her divorce from Don she has had little do except behave badly within her own sphere. Here, though, her plot line comments on the others without becoming a mere echo of them.

In keeping with the show’s increasingly urban focus and its representation of the suburbs as a kind of exile, Betty and Henry find themselves ill at ease in the city. When Betty lets herself wander around Don and Megan’s apartment with an appraising eye, she self-consciously checks her appearance in a mirror and clumsily bumps into a lamp, as if she is literally too large for their chic apartment. When she walks to the window to check out the view, she is surprised by the sight of Megan getting dressed across the patio. As the new Mrs. Draper, Megan is the object of highly ambivalent feelings on Betty’s part. She is young, beautiful, and enjoys the love that Betty wanted but which Don was unable or unwilling to give her. She represents a kind of previous self for Betty, but also a mirror image. She has what Betty wants, but she also occupies a position that Betty notably gave up. And even though we can see the pain it causes Betty to be reminded of her insecurities, the fact that she continues to look suggests a kind of pleasure. (And why exactly is that whale smiling like some kind of aquatic Saint Teresa?)

When we see Betty again, she is compensating for her surreptitious glimpse of Megan by surreptitiously filling up her mouth with Reddi-Whip, a pleasure that is emphatically substitutive, and, although tempting, far from irresistible. That this scene comes immediately after Don’s “sinfully delicious” line only underlines its emptiness. (In “Lady Lazarus,” Don unconvincingly explains that Cool Whip is not “fake whipped cream,” but a “nondairy whipped topping” that “comes frozen.” Don and Megan then act out a proposed commercial in which they play a happy couple, with Megan urging the dessert on her husband, an exchange that itself recalls the incident in “Faraway Places” in which Don and Megan fight over orange sherbet-as-symbol-of-faked-pleasure.)

Betty struggles in this episode to assert control over her body and her emotions. She uses Weight Watchers as a kind of group-therapy-lite where she can share highly abridged stories and receive support. In another scene of eating, she catches Henry sneaking a pork chop, but instead of getting angry or upset, as the Betty of last season might have done, she helps him and listens sympathetically to his story of political miscalculation. Henry worries that he’s “bet on the wrong horse” and “jumped ship for nothing,” a concern that we could imagine Betty sharing: did she make the right decision to leave Don for Henry? But she reaffirms her commitment, telling him that “I’m here to help you, as you’re here to help me.” Betty is self-aware and generous here, but studiedly, as if it’s a new behavior she’s learned about in class but never really tried out before.

That she slips up again when she comes across Don’s genuinely sweet note to Megan is understandable, since it represents exactly the kind of honest love that he withheld from her. Setting her jaw against her own misgivings, she plants just the seed that she knows will feed Sally’s pre-adolescent resentment and enrage Don. (“I don’t know why Megan didn’t tell you,” she says after eating a celery stick.)

These plots to undermine rivals often have a way of temporarily empowering the younger characters that are enlisted to do the work of their elders: Sally gets to confront Megan with her new secret, Jane gets the promise of a new life in a new apartment, and Ginsberg prematurely declaims “Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!” The quotation of Shelley’s poem is especially apropos, both to the episode and to the series in general (I’m thinking especially of debates about Mad Men’s representation of the 1960s), since it presents history as a sublime ruin rather than as progress or the endurance of any particular human creation.

Of these, Sally’s story is perhaps the most interesting. At the beginning of the episode, we see Megan teaching her to fake tears to get what she wants. Megan might have thought she was teaching Sally useful skills of manipulation, but Sally has learned from more seasoned operators, and painfully one-ups her with accusations of betrayal. When she realizes how her mother was trying to use her, Sally turns it back on Betty, knowing that the most effective way to hurt her is to pretend that nothing is wrong. Sally probably thinks that she is merely doing her best to hold her own ground against the deception and turpitude of the old, but her behavior says just as much about the ignorant ruthlessness of the young.

When, as so often in this show, characters find their victories turn out to be hollow, what is the solution? In the final Thanksgiving scene, Betty says “I’m thankful I have everything I want, and no one has anything better.” Can we hear this as a step down the path of maturity, an attempt to give up desiring what she can’t have by focusing on Weight Watchers’ brand of self-improvement? Or is it an Ozymandias-like display of false pride, a retreat into infantile self-absorption no better than Bobby’s appreciation for having two really big houses? In this case, the look on Betty’s face as she tastes her pathetically measured out turkey dinner says more than I can: the ecstasy of tasting a deferred pleasure and despair at its limitedness, followed by something like acceptance.