[The fifth in the Unit for Criticism's multi-authored series of posts on Season 7 of AMC's Mad Men, posted in collaboration with the publication ofMADMEN, MAD WORLD: Sex, Politics, Style, andthe 1960s(Duke University Press, March 2013) Eds. Lauren M. E. Goodlad, Lilya Kaganovsky and Robert A. Rushing]

"Loyalty"

Written by: Caroline Levine (University of Wisconsin-Madison)

“The Runaways” was an episode that returned us again and again to questions of loyalty, and I found myself wondering whether the show might be referring in some way to the precarious loyalty of its audiences. Ratings have dipped over time. Lots of viewers have been willing to let Mad Men go, and if my acquaintance is anything to go by, many who have stuck with it are more disappointed than satisfied, their commitment to watching now brittle and strained.

Of course, the series’ slow pace has always been hard on those who are afraid of commitment. Critic Logan Hill says, “It’s a show that has always been built for the obsessive fan, and hasn’t really cared very much for the casual fan… It’s been kind of cocky about that.” Casual—like the worker who lounges on the sofa or like the boyfriend who would rather go back to jail than stick with the mother of his child. If Mad Men has always sought a loyal, committed relationship with us rather than a sequence of one-night stands, its characters’ stories, dominated break-ups and firings, haven’t given us great models.

Should we be more loyal? Should “guys like us” stick together, as Harry Crane says, because “we go back a long way”? Should we try to do our best to make sure that Mad Men is “still important,” even though we are really having trouble figuring out exactly how to do so? Certainly loyalty feels like a troubling value coming from a Philip Morris executive, who moralizes that his company “won’t turn on his friends as easily” as Don does. It’s tough to be inspired by those who stick to their friends precisely so that they can go on killing them.

Mad Men teaches us a lot more about falling out of love than about building loyalty. But then what, exactly, has happened to the relationship between the show and its audiences? Perhaps these days we are more likely to dally with Game of Thrones, to be excited by True Detective or Top of the Lake. But what was it that attracted us to Mad Men in the first place, and what’s turning us off or splitting us up now?

There were once many kinds of attraction. Some who loved the first seasons fell for the early sixties style, and dwelled happily on the elegant clothes and sleek furniture. The late sixties is now quite deliberately betraying that style. Don looks awkward in his sports shirt compared to Megan’s sexy dance partner, and beautiful Stephanie clearly needs a bath. The couch that used to be an object of desire is now in the wrong spot and too heavy to move.

Another group who loved Mad Men in its youth were drawn to its richness as historical fiction. From casual racism to littering to drugged childbirth, Mad Men invited us to imagine a time just long enough ago to feel distant, just close enough to feel familiar. Matthew Weiner is famously obsessed with historically authentic detail, and the show has always raised interesting, troubling questions about his glossy, glamorous version of an old boy past. These days, the show offers up a world that feels less gorgeous and less exclusive, and yet not ever radically disruptive enough. It’s a hodge podge of approaches to life—West Coast as well as East, hippie commune emerging out of suburban elite, behatted executives alongside beards and miniskirts—that won’t let us settle into a single, smooth vision of the past (nostalgic or critical as the case may be).

Some early viewers were just there for the plot. It started out a really good one: we were drawn into the precariousness of a life built on secrets. Would exposure of Don’s past unsettle his career, with his talent for seducing us with appearances? Would plotting blue-blooded Pete take down Don, the social impostor? That plot is distant, now. We’ve had some good dramatic tension since that has been organized around the success or failure of the company, and yet those moments too feel far away in this season. The narrative is not just slow but motiveless. Don seems to be sinking slowly, or is he rising again? Joan has climbed to the top and seems secure there. Peggy remains single. Roger sits perched pretty well in his own complacency. There’s no suspense here, no readiness for sudden crisis or revelation.

For many audiences, the series once did really well when it came to complex and richly rounded characters. Especially the white women who were trying to figure out how to live satisfying lives: Peggy, Joan, Betty, and Sally. Pete was also fascinating in his aspiration to succeed, and amoral Roger was disturbingly charming. All of them have receded into minorness now. The number of characters has expanded, but most are forgettable. Who is that Cutler, again? Who are the many boy creatives who laugh at Lou?

The show holds on, wrongly I think, to a loyalty to Don as its central character. Megan’s a frustrating figure, I believe, in part because she too keeps up her hungry adoration for Don. She holds him too much at the center, just as the show does. In “Runaways,” she’s first warm to Stephanie, and then suddenly jealous when Stephanie blurts that she knows all of Don’s secrets. Megan drives Stephanie away, despite her promise to hold on to her for Don. Megan then tries to make herself important to Don by making him feel important, at the center of a sexy threesome: will sharing him with Amy, whom he has continually tried to reject and dismiss, put Megan back at the center? Structurally, this seems like a strategy that can’t possibly work. It’s as though Mad Men both did and did not get its own message that it’s impossible to try to organize a meaningful life around a debonair professional ad man.

If the series has turned off audiences by failing to deliver up some of its earlier pleasures—pleasures of style, historical detail, suspenseful plot, and complex character—one place where it continues strong is in the complex interweaving of its themes. Advertising brings together seduction and work, social climbing and courtship, nostalgia and strategy. There are rich resonances in every episode.

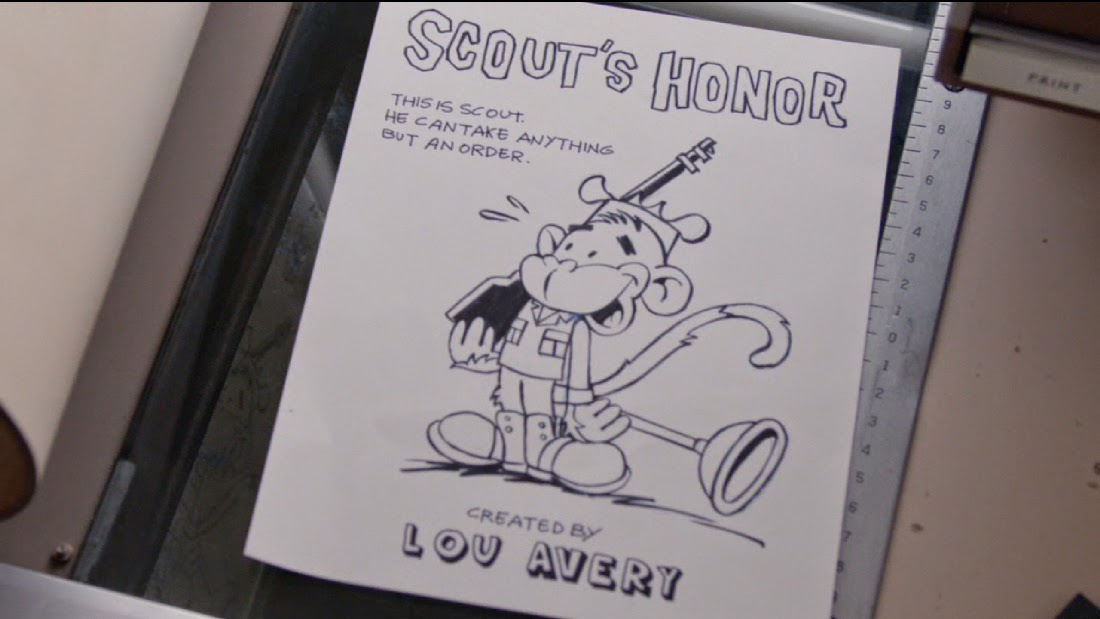

In “Runaways,” for example, Lou’s absurd dream of a wholesome Saturday cartoon that upholds values of patriotism and loyalty finds intriguing echoes in both Megan and Betty, “who can take anything but an order.” Betty rebels against Henry’s authority, paradoxically, when she holds on to her right to speak up in favor of traditional authority and against youthful rebellion. “Leave the thinking to me,” Henry orders. This command never works in Mad Men, where women always refuse this particular model of loyalty. As Betty says simply, “I can think all by myself.” Meanwhile, the computer, which poor paranoid Michael is not entirely wrong to see as coming for all of us, hums away where the writers and artists used to work, literally taking the place of human thought.

Mad Men plants echoes in its smallest details. Two characters in this episode passingly exclaim that Megan’s apartment is “out of sight,” at once offering up a little pieces of sixties lingo and hinting at the distance between what is on view—Stephanie’s “obvious” pregnancy, exposed in a public phone booth—and what is protected from prying eyes. Betty and Stephanie both refuse to eat outside, asserting their will by remaining, each in her own way, out of sight.

This thematic interweaving is a very literary pleasure. As a literary critic myself, I was trained to notice such patternings, and I love to feel their richness, and to unravel the connections. Other television often fails at this, even when it does well on other grounds. And for this viewer, it is enough to keep me coming back to Mad Men.

I can’t imagine that simple loyalty—just “going back a long way"—will work for audiences in part because Mad Men simply doesn’t teach us loyalty as a value. It goes so far as to mock its characters’ demands for loyalty, and its plot thrives precisely where loyalty fails. Perhaps the show knows it needs to woo us in some other way. It’s no accident that Don spells “strategy” carefully in “Runaways” and concludes the episode with a surprising new strategy for the cigarette business. But then again, as Lou says, it may be too late for that now.

"Loyalty"

Written by: Caroline Levine (University of Wisconsin-Madison)

“The Runaways” was an episode that returned us again and again to questions of loyalty, and I found myself wondering whether the show might be referring in some way to the precarious loyalty of its audiences. Ratings have dipped over time. Lots of viewers have been willing to let Mad Men go, and if my acquaintance is anything to go by, many who have stuck with it are more disappointed than satisfied, their commitment to watching now brittle and strained.

Of course, the series’ slow pace has always been hard on those who are afraid of commitment. Critic Logan Hill says, “It’s a show that has always been built for the obsessive fan, and hasn’t really cared very much for the casual fan… It’s been kind of cocky about that.” Casual—like the worker who lounges on the sofa or like the boyfriend who would rather go back to jail than stick with the mother of his child. If Mad Men has always sought a loyal, committed relationship with us rather than a sequence of one-night stands, its characters’ stories, dominated break-ups and firings, haven’t given us great models.

Should we be more loyal? Should “guys like us” stick together, as Harry Crane says, because “we go back a long way”? Should we try to do our best to make sure that Mad Men is “still important,” even though we are really having trouble figuring out exactly how to do so? Certainly loyalty feels like a troubling value coming from a Philip Morris executive, who moralizes that his company “won’t turn on his friends as easily” as Don does. It’s tough to be inspired by those who stick to their friends precisely so that they can go on killing them.

Mad Men teaches us a lot more about falling out of love than about building loyalty. But then what, exactly, has happened to the relationship between the show and its audiences? Perhaps these days we are more likely to dally with Game of Thrones, to be excited by True Detective or Top of the Lake. But what was it that attracted us to Mad Men in the first place, and what’s turning us off or splitting us up now?

There were once many kinds of attraction. Some who loved the first seasons fell for the early sixties style, and dwelled happily on the elegant clothes and sleek furniture. The late sixties is now quite deliberately betraying that style. Don looks awkward in his sports shirt compared to Megan’s sexy dance partner, and beautiful Stephanie clearly needs a bath. The couch that used to be an object of desire is now in the wrong spot and too heavy to move.

Another group who loved Mad Men in its youth were drawn to its richness as historical fiction. From casual racism to littering to drugged childbirth, Mad Men invited us to imagine a time just long enough ago to feel distant, just close enough to feel familiar. Matthew Weiner is famously obsessed with historically authentic detail, and the show has always raised interesting, troubling questions about his glossy, glamorous version of an old boy past. These days, the show offers up a world that feels less gorgeous and less exclusive, and yet not ever radically disruptive enough. It’s a hodge podge of approaches to life—West Coast as well as East, hippie commune emerging out of suburban elite, behatted executives alongside beards and miniskirts—that won’t let us settle into a single, smooth vision of the past (nostalgic or critical as the case may be).

Some early viewers were just there for the plot. It started out a really good one: we were drawn into the precariousness of a life built on secrets. Would exposure of Don’s past unsettle his career, with his talent for seducing us with appearances? Would plotting blue-blooded Pete take down Don, the social impostor? That plot is distant, now. We’ve had some good dramatic tension since that has been organized around the success or failure of the company, and yet those moments too feel far away in this season. The narrative is not just slow but motiveless. Don seems to be sinking slowly, or is he rising again? Joan has climbed to the top and seems secure there. Peggy remains single. Roger sits perched pretty well in his own complacency. There’s no suspense here, no readiness for sudden crisis or revelation.

For many audiences, the series once did really well when it came to complex and richly rounded characters. Especially the white women who were trying to figure out how to live satisfying lives: Peggy, Joan, Betty, and Sally. Pete was also fascinating in his aspiration to succeed, and amoral Roger was disturbingly charming. All of them have receded into minorness now. The number of characters has expanded, but most are forgettable. Who is that Cutler, again? Who are the many boy creatives who laugh at Lou?

The show holds on, wrongly I think, to a loyalty to Don as its central character. Megan’s a frustrating figure, I believe, in part because she too keeps up her hungry adoration for Don. She holds him too much at the center, just as the show does. In “Runaways,” she’s first warm to Stephanie, and then suddenly jealous when Stephanie blurts that she knows all of Don’s secrets. Megan drives Stephanie away, despite her promise to hold on to her for Don. Megan then tries to make herself important to Don by making him feel important, at the center of a sexy threesome: will sharing him with Amy, whom he has continually tried to reject and dismiss, put Megan back at the center? Structurally, this seems like a strategy that can’t possibly work. It’s as though Mad Men both did and did not get its own message that it’s impossible to try to organize a meaningful life around a debonair professional ad man.

If the series has turned off audiences by failing to deliver up some of its earlier pleasures—pleasures of style, historical detail, suspenseful plot, and complex character—one place where it continues strong is in the complex interweaving of its themes. Advertising brings together seduction and work, social climbing and courtship, nostalgia and strategy. There are rich resonances in every episode.

In “Runaways,” for example, Lou’s absurd dream of a wholesome Saturday cartoon that upholds values of patriotism and loyalty finds intriguing echoes in both Megan and Betty, “who can take anything but an order.” Betty rebels against Henry’s authority, paradoxically, when she holds on to her right to speak up in favor of traditional authority and against youthful rebellion. “Leave the thinking to me,” Henry orders. This command never works in Mad Men, where women always refuse this particular model of loyalty. As Betty says simply, “I can think all by myself.” Meanwhile, the computer, which poor paranoid Michael is not entirely wrong to see as coming for all of us, hums away where the writers and artists used to work, literally taking the place of human thought.

Mad Men plants echoes in its smallest details. Two characters in this episode passingly exclaim that Megan’s apartment is “out of sight,” at once offering up a little pieces of sixties lingo and hinting at the distance between what is on view—Stephanie’s “obvious” pregnancy, exposed in a public phone booth—and what is protected from prying eyes. Betty and Stephanie both refuse to eat outside, asserting their will by remaining, each in her own way, out of sight.

This thematic interweaving is a very literary pleasure. As a literary critic myself, I was trained to notice such patternings, and I love to feel their richness, and to unravel the connections. Other television often fails at this, even when it does well on other grounds. And for this viewer, it is enough to keep me coming back to Mad Men.

I can’t imagine that simple loyalty—just “going back a long way"—will work for audiences in part because Mad Men simply doesn’t teach us loyalty as a value. It goes so far as to mock its characters’ demands for loyalty, and its plot thrives precisely where loyalty fails. Perhaps the show knows it needs to woo us in some other way. It’s no accident that Don spells “strategy” carefully in “Runaways” and concludes the episode with a surprising new strategy for the cigarette business. But then again, as Lou says, it may be too late for that now.