[The seventh in the Unit for Criticism's multi-authored series of posts on Season 7 of AMC's Mad Men, posted in collaboration with the publication ofMADMEN, MAD WORLD: Sex, Politics, Style, andthe 1960s(Duke University Press, March 2013) Eds. Lauren M. E. Goodlad, Lilya Kaganovsky and Robert A. Rushing]

"Let’s Have Another Piece of Pie"

Written by: Lauren M. E. Goodlad (Illinois).

The term pastiche has become synonymous with postmodernism and the reign of signifiers detached from deeper reference or history. But as the Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics reminds us, long before pastiche developed its postmodern connotation of using “recognizable ingredients” while offering “no new substance,” the word derived from the Italian for pasticcio “or a hodge-podge of pie containing both meat and pasta.” To say that “Waterloo,” Mad Men’s Season 7 "mid-season finale" is pastiche, is not to condemn a series that, back in 2010, I argued was anything but. For at that time the show—still embedded in the pre-counterculture milieu of the early 60s—turned on a masterful dialectics between historical events like the Kennedy assassination and our own turn-of-the millennium emergencies. Those early-60s stories (as I wrote last June), “in inflecting our imaginary with the ‘history’ we had forgotten to remember as such, added something quite distinct to what we could take for the history of our present.” Yes, Mad Men has changed as it nears its final curtain; and as Caroline Levine wrote two weeks ago, many once-ardent viewers have wearied of its charms. Yet, I, for one, was happy enough last night to pull up a chair and join Roger in the spirit of Irving Berlin’s Depression-era ditty. “Let’s Have Another Cup of Coffee,” I say, with a nice hodge-podge of meat and pasta on the side.

Of course, Mad Men has always sported a playful self-consciousness, even during episodes of stunning high seriousness. Almost inevitably, the show has begun paying tribute to its own greatest moments: last week by staging an homage to Season 4’s “The Suitcase”and this week, on the occasion of Bert’s death, by recalling us to Joan’s promptitude in Season 1 when she joined Bert in alerting clients to what then looked like Roger’s imminent demise (“The Long Weekend”).

Even more explicitly, Roger’s plan to become a McCann subsidiary and so to make everyone richer while thwarting Cutler’s scheme to ditch Don, harked back to Don’s Season 3 ploy to save the agency by starting anew. (It also made Cutler the ultimate Napoleon of this Waterloo story.) The threat back then was a British invasion at the hands of the downsizing raiders, Putnam, Powell & Lowe. Now, in a comparable instance of “the agency of the future” evoking our latter-day perils, Cutler is determined to trade creative juices for big data analysis. (In fact, the dystopian vision of turning advertising into a pure science has haunted the industry since the days when David Ogilvy and Rosser Reeves first put on their grey flannel suits: something Mad Men has meditated in episodes like Season 1’s “The Hobo Code.”)

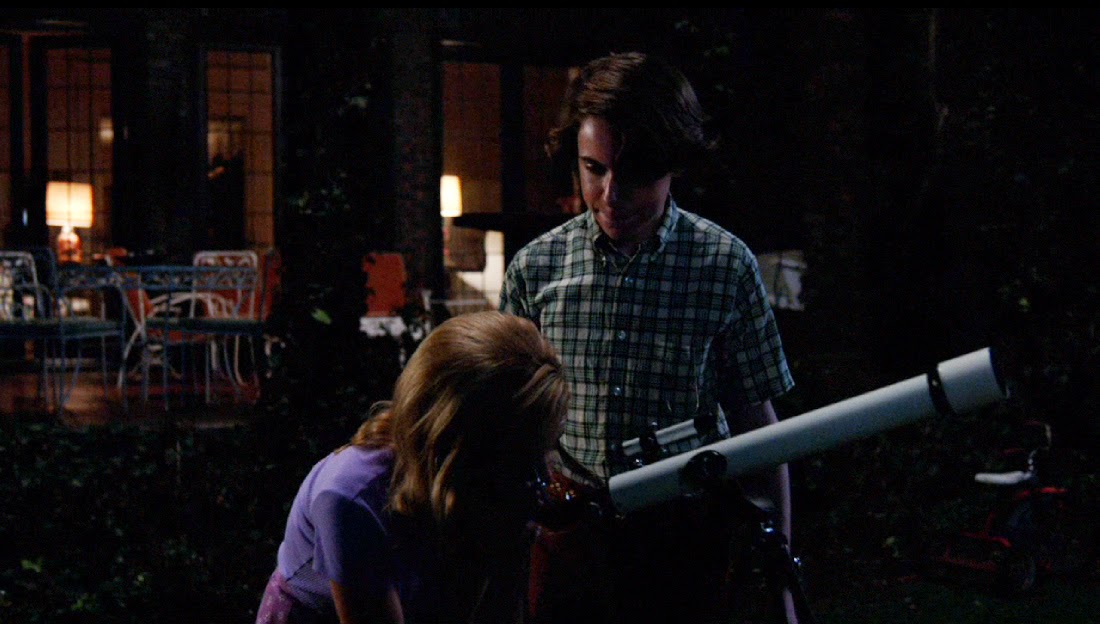

In yet another familiar motif, recurring television footage from a world-historical event—in this instance Apollo 11’s July 29, 1969 “giant step for [a] man”—threads through the storylines of the show’s characters, inflecting Peggy’s pitch for Burger Chef and Sally’s ongoing coming-of-age. (Will Sally one day tell her daughter that a boy named Neil showed her the stars on the night Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, just as Betty once told us that a Jewish boy kissed her at a school fundraiser for Holocaust survivors?)

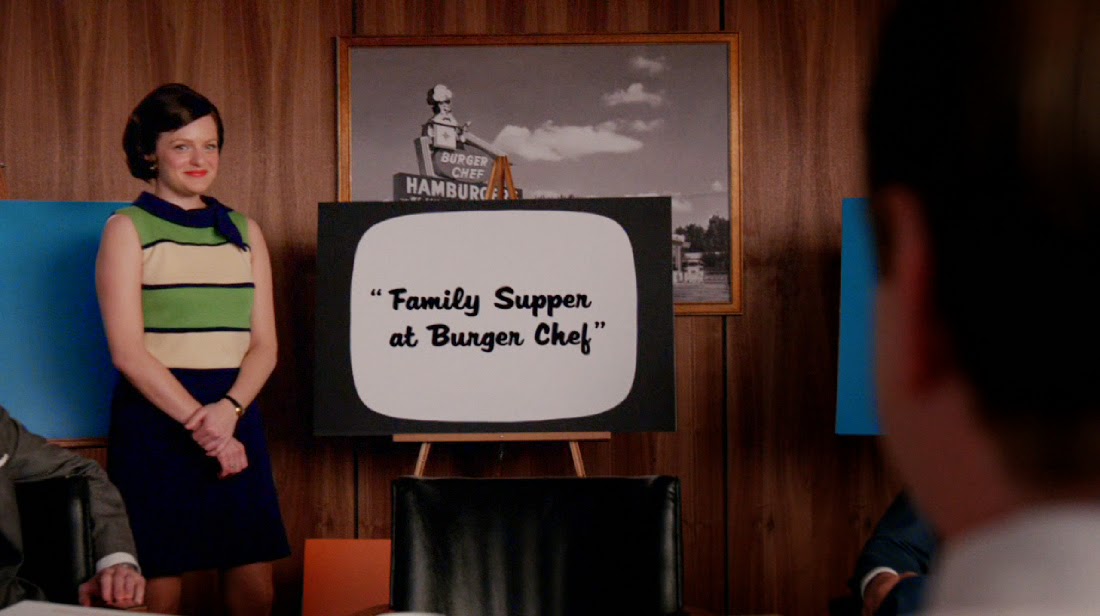

There was much else going on in “Waterloo” besides these multiple nods to Mad Men’s glory days, to suggest a newfound delight in postmodern composition—one that is not (or not immediately) reducible to the dour Jamesonian diagnosis of pastiche as “speech in [the] dead language” of late-capitalism. Witness, for example, the show’s reflection on its own serial delivery as Peggy tells the fast food execs that it wasn’t just technology that made the moon walk so special but, rather, the fact that “All of us were doing the same thing at the same time.” “We can still feel the pleasure of that connection,” she assures them. Last week, Don supported Peggy’s instinct to swap out the fantasy of a dad who brings Burger Chef to the family home for the more radical idea that fast food joints are a homely refuge from modern discord. If Mad Men drew the line at a marriage of convenience between Bob Benson and Joan, it made crystal clear that Pete, Don and Peggy were a bona fide family—in fact, the only family left intact in the wake of a retreating Megan, a lonely Peggy, and a Pete still more caught up in what he’s lost than in his new liaison with a real estate agent.

By merging the new campaign, “Family Supper at Burger Chef," with the tableaux of families all over the nation, driven to the tube by their collective hunger for connection, Mad Men once again had its cake and ate it too. “The dinner table is your battlefield and your prize,” Peggy told the burger execs, because the TV is only six feet away from the kitchen, droning disruptively of cold war adventures, distracting us from each other, and dividing Dad’s taste for Sinatra from Junior’s preference for the Stones. But as Mad Men’s camera took us from Betty’s living room, to Peggy and Don’s motel, Bert’s living room with his housekeeper, and even chez Roger and Mona (!), television was no longer the great despoiler. Not a spout for noxious news, noise, and niche marketing, the television we saw in “Waterloo,” though pictured in the form of a walk on the moon, was clearly an allegory for long form serial television itself. There it was in glorious mise en abyme: us sitting in the dark watching them sitting in the dark as Mad Men telegraphed the story of its own years-long gambit; those slow narrative installments, synchronized over time, embedding fictional characters in the existential space of day-to-day living that last week’s episode called “Living in the Not Knowing.” We know that space well because we live in it too.

Now, as I said at the start, I am not (or not strongly) resisting Mad Men’s postmodern turn but I do think it means that the show may never answer the questions Bruce Robbins posed in his opening blog on the Season 7 premiere. Bruce asked, would the moral redemption prophesied at the end of last season mean that the show would need to turn against "advertising itself"? And, if so, “Wouldn’t a rejection of all that professional success mean turning against the vice-ridden virtues by which viewers have been so charmed?” “In particular, what would a critique of the profession mean for the gradual emergence of women into the ranks of the professionally successful?” In “Waterloo,” these searching questions are banished by the same self-referential trick that turns “Family Supper at Burger Chef” into “Watching Season 7 of Mad Men.” That is, through the same postmodern device, the episode is less about Jim Cutler’s dumb idea to rid the agency of what Pete memorably calls “a very valuable piece of horse flesh” than it is about the hazards of bringing a landmark serial television show to the brink of its… “mid-season finale” (on this aberration I cannot do better than Sean O’Sullivan). “Every great ad tells a story,” we learn twice in this episode. But the message is not that Mad Men is a story about a great ad for Burger Chef; rather,Burger Chef is an ad for a great story called Mad Men.

To be sure, early in the episode we learn that Ted now occupies the position of the damaged existential subject and directly blames advertising: “I don’t want to die,” he assures his astonished colleagues, “I just don’t want to do this anymore.” Toward the end of the episode, Don tries to persuade Ted that it’s the business side of the job that is soul-destroying. Pitching to Ted harder than Peggy did to Burger Chef, Don assures his former partner that when all is said and done, straight up copywriting is as good as it gets: “You don’t want to see what happens when it’s really gone,” says the man who has spent the season occupying the office where Lane Pryce hanged himself. Feeling as we do that the work in question isn’t so much flacking for fast food as writing for television, we can almost believe in Don’s newfound Gospel of Work. We can certainly believe that a showrunner like Matthew Weiner is sometimes “tired of fighting”—fighting not only for maximum loot but also for screen time in a business in which every extra second of extra air time for Mercedes Benz, Burger King, and AMC promotions adds considerably more to the bottom line. Year after year, swimming in a pool of industry sharks who probably make “Benedict Joan” look like Mother Teresa and Jim Cutler look like a fresh-faced Michael Kuzak, who doubts that Weiner has days when he feels ready to cash out his shares and spend the rest of his life on an island in the South Atlantic Ocean?

Yet another way that Mad Men defers the Robbins question is by placing Peggy outside the maw of advertising—making her situation so riddled by sexism that we sympathize too much to worry if she is becoming another suit. At the end of last season with Don on the ropes, Peggy looked to be taking her mentor’s place, pantsuit and all. Instead it is Lou who has played the part of the Man in Season 7, while Peggy has struggled with a moribund love life and undermined confidence. Last week Pete—against the ironic backdrop of his own domestic dysfunction—persuaded Peggy to let Don do his magic. As a woman, Pete told her, she must stand for a maternal presence even though the only child in her life is her young neighbor Julio. This week, watching her hold up two outfits for Julio’s advice—a grey color that “men wear” and a stripey number that is “pretty” but may make her sweat—we know that there is no winning choice for Peggy. Chafing against a clueless stereotype of femininity, her only recourse is to suck it up.

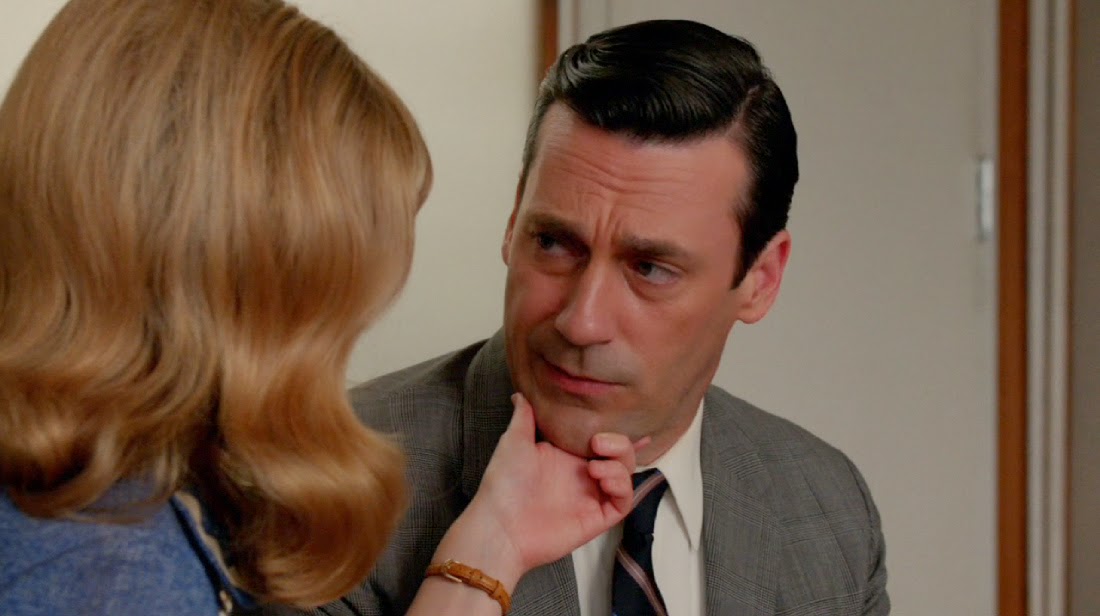

The upside of this lapse of confidence on Peggy’s part is the return of Don as avuncular mentor. I must confess that I am a complete sucker for this aspect of the Draper persona. The genius of this character is that he is sometimes quite believably the professional woman’s friend: an icon of alpha male confidence that a woman like Peggy can simply summon before her as though he were the working gal’s answer to Barbara Eden in a bottle. It helps that the Don of Season 7 has so far been a recovering Lothario. Not since Neve Campbell propositioned him in the premiere have we sensed that infidelity is very much on his mind. (We can’t count the threesome with Megan’s friend in “The Runaways” since that was her idea). Indeed, so chaste has Don become that, in another homage to the past, this one parodic, Don’s daffy secretary takes matters in her own hands and offers herself as solace for his troubles. The scene takes us back to a rather more successful secretarial seduction in Season 4 when Megan persuaded her boss that she could be discreet. In that episode, alcohol played a role in prompting Don to take the risk (and be unfaithful to Faye Miller). But the Don of Season 7 has come back from his Elba with womanizing and heavy drinking seemingly a thing of the past.

Not only the heart of “The Suitcase,” but also of the entire 3-season arc that preceded it, Don’s bond with Peggy has always been one of the show’s most compelling setpieces. Far be it from me to spoil the fun. Ah, but, Mad Men, Mad Men are there no moonshot stories we wish to pitch before releasing Don and his friends from Purgatorio? Whether embodied by Don, Freddy Rumsen, Ted, Peggy or that Mad Man Behind the Curtain, Weiner himself, are we really ready to declare that The Writer For Our Times is some good-enough cross between Walter Benjamin’s “The Storyteller” and the crooner in a Hollywood musical? (Bert’s posthumous appearance in a song-and-dance number—a hodge-podge of meat and pasta if ever there was one—is the episode's biggest reveal: the final referent for “Waterloo” is not Napoleon, it’s Abba!) My point is not that the best things in life aren’t free. Nonetheless, in taking the occasion of a “giant step for mankind” for a clever pastiche about Mad Men’s own history, the show missed the opportunity to make JFK’s determination to get to the moon by the end of the 1960s meaningful for our times.

Yes, there were doubtless many back then who noted (like Neil and Sally) that the government’s quixotic Cold War extravaganza was costing billions of dollars sorely needed on Earth. But what Mad Men did not pause to contemplate was how few people at the time rejected the possibility of fighting Communism, a War on Poverty, and exploring the final frontier all while expanding affordable higher education. For both better and worse—on behalf of many regrettable causes as well as good ones--these were times when Republicans like Richard Nixon (or Henry Francis) shared the basic liberal premise that the purpose of government is to do all the things that individuals cannot do and markets will not do. Missed, therefore, by Mad Men last night was the chance to refract the stifled aspirations of our own times. Frozen in a neoliberal austerity regime, we are assured that we can no longer shoot for the moon—not for renewable energy, affordable education, universal healthcare, or any other public good. Thus, the great story behind every ad today is not (or not only) our craving for lost connections; it's the never-ending neoliberal story that, give or take a few Middle East invasions, drone strikes, and ambitious surveillance programs, government’s job in the twenty-first century is to do the bidding of Job Creators.

When Don tells Sally she should not be so “cynical,” we sense he is right. But what kind of moon should we shoot for, daddy? Watching Mad Men last night, I longed for a crazy coot like Season 3’s Conrad Hilton to give us some glimmer of what the moon is for. What I got instead—Bert in a scene from the 1950s-meets-Mama Mia!—may well be the next best thing. But if “Waterloo” was not quite penned in the dead language of late capitalism, it was the vision of a show already convinced that the best thing to come from our turn-of-the-millennium is the advent of serial television.

"Let’s Have Another Piece of Pie"

Written by: Lauren M. E. Goodlad (Illinois).

The term pastiche has become synonymous with postmodernism and the reign of signifiers detached from deeper reference or history. But as the Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics reminds us, long before pastiche developed its postmodern connotation of using “recognizable ingredients” while offering “no new substance,” the word derived from the Italian for pasticcio “or a hodge-podge of pie containing both meat and pasta.” To say that “Waterloo,” Mad Men’s Season 7 "mid-season finale" is pastiche, is not to condemn a series that, back in 2010, I argued was anything but. For at that time the show—still embedded in the pre-counterculture milieu of the early 60s—turned on a masterful dialectics between historical events like the Kennedy assassination and our own turn-of-the millennium emergencies. Those early-60s stories (as I wrote last June), “in inflecting our imaginary with the ‘history’ we had forgotten to remember as such, added something quite distinct to what we could take for the history of our present.” Yes, Mad Men has changed as it nears its final curtain; and as Caroline Levine wrote two weeks ago, many once-ardent viewers have wearied of its charms. Yet, I, for one, was happy enough last night to pull up a chair and join Roger in the spirit of Irving Berlin’s Depression-era ditty. “Let’s Have Another Cup of Coffee,” I say, with a nice hodge-podge of meat and pasta on the side.

Of course, Mad Men has always sported a playful self-consciousness, even during episodes of stunning high seriousness. Almost inevitably, the show has begun paying tribute to its own greatest moments: last week by staging an homage to Season 4’s “The Suitcase”and this week, on the occasion of Bert’s death, by recalling us to Joan’s promptitude in Season 1 when she joined Bert in alerting clients to what then looked like Roger’s imminent demise (“The Long Weekend”).

Even more explicitly, Roger’s plan to become a McCann subsidiary and so to make everyone richer while thwarting Cutler’s scheme to ditch Don, harked back to Don’s Season 3 ploy to save the agency by starting anew. (It also made Cutler the ultimate Napoleon of this Waterloo story.) The threat back then was a British invasion at the hands of the downsizing raiders, Putnam, Powell & Lowe. Now, in a comparable instance of “the agency of the future” evoking our latter-day perils, Cutler is determined to trade creative juices for big data analysis. (In fact, the dystopian vision of turning advertising into a pure science has haunted the industry since the days when David Ogilvy and Rosser Reeves first put on their grey flannel suits: something Mad Men has meditated in episodes like Season 1’s “The Hobo Code.”)

In yet another familiar motif, recurring television footage from a world-historical event—in this instance Apollo 11’s July 29, 1969 “giant step for [a] man”—threads through the storylines of the show’s characters, inflecting Peggy’s pitch for Burger Chef and Sally’s ongoing coming-of-age. (Will Sally one day tell her daughter that a boy named Neil showed her the stars on the night Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, just as Betty once told us that a Jewish boy kissed her at a school fundraiser for Holocaust survivors?)

There was much else going on in “Waterloo” besides these multiple nods to Mad Men’s glory days, to suggest a newfound delight in postmodern composition—one that is not (or not immediately) reducible to the dour Jamesonian diagnosis of pastiche as “speech in [the] dead language” of late-capitalism. Witness, for example, the show’s reflection on its own serial delivery as Peggy tells the fast food execs that it wasn’t just technology that made the moon walk so special but, rather, the fact that “All of us were doing the same thing at the same time.” “We can still feel the pleasure of that connection,” she assures them. Last week, Don supported Peggy’s instinct to swap out the fantasy of a dad who brings Burger Chef to the family home for the more radical idea that fast food joints are a homely refuge from modern discord. If Mad Men drew the line at a marriage of convenience between Bob Benson and Joan, it made crystal clear that Pete, Don and Peggy were a bona fide family—in fact, the only family left intact in the wake of a retreating Megan, a lonely Peggy, and a Pete still more caught up in what he’s lost than in his new liaison with a real estate agent.

By merging the new campaign, “Family Supper at Burger Chef," with the tableaux of families all over the nation, driven to the tube by their collective hunger for connection, Mad Men once again had its cake and ate it too. “The dinner table is your battlefield and your prize,” Peggy told the burger execs, because the TV is only six feet away from the kitchen, droning disruptively of cold war adventures, distracting us from each other, and dividing Dad’s taste for Sinatra from Junior’s preference for the Stones. But as Mad Men’s camera took us from Betty’s living room, to Peggy and Don’s motel, Bert’s living room with his housekeeper, and even chez Roger and Mona (!), television was no longer the great despoiler. Not a spout for noxious news, noise, and niche marketing, the television we saw in “Waterloo,” though pictured in the form of a walk on the moon, was clearly an allegory for long form serial television itself. There it was in glorious mise en abyme: us sitting in the dark watching them sitting in the dark as Mad Men telegraphed the story of its own years-long gambit; those slow narrative installments, synchronized over time, embedding fictional characters in the existential space of day-to-day living that last week’s episode called “Living in the Not Knowing.” We know that space well because we live in it too.

Now, as I said at the start, I am not (or not strongly) resisting Mad Men’s postmodern turn but I do think it means that the show may never answer the questions Bruce Robbins posed in his opening blog on the Season 7 premiere. Bruce asked, would the moral redemption prophesied at the end of last season mean that the show would need to turn against "advertising itself"? And, if so, “Wouldn’t a rejection of all that professional success mean turning against the vice-ridden virtues by which viewers have been so charmed?” “In particular, what would a critique of the profession mean for the gradual emergence of women into the ranks of the professionally successful?” In “Waterloo,” these searching questions are banished by the same self-referential trick that turns “Family Supper at Burger Chef” into “Watching Season 7 of Mad Men.” That is, through the same postmodern device, the episode is less about Jim Cutler’s dumb idea to rid the agency of what Pete memorably calls “a very valuable piece of horse flesh” than it is about the hazards of bringing a landmark serial television show to the brink of its… “mid-season finale” (on this aberration I cannot do better than Sean O’Sullivan). “Every great ad tells a story,” we learn twice in this episode. But the message is not that Mad Men is a story about a great ad for Burger Chef; rather,Burger Chef is an ad for a great story called Mad Men.

To be sure, early in the episode we learn that Ted now occupies the position of the damaged existential subject and directly blames advertising: “I don’t want to die,” he assures his astonished colleagues, “I just don’t want to do this anymore.” Toward the end of the episode, Don tries to persuade Ted that it’s the business side of the job that is soul-destroying. Pitching to Ted harder than Peggy did to Burger Chef, Don assures his former partner that when all is said and done, straight up copywriting is as good as it gets: “You don’t want to see what happens when it’s really gone,” says the man who has spent the season occupying the office where Lane Pryce hanged himself. Feeling as we do that the work in question isn’t so much flacking for fast food as writing for television, we can almost believe in Don’s newfound Gospel of Work. We can certainly believe that a showrunner like Matthew Weiner is sometimes “tired of fighting”—fighting not only for maximum loot but also for screen time in a business in which every extra second of extra air time for Mercedes Benz, Burger King, and AMC promotions adds considerably more to the bottom line. Year after year, swimming in a pool of industry sharks who probably make “Benedict Joan” look like Mother Teresa and Jim Cutler look like a fresh-faced Michael Kuzak, who doubts that Weiner has days when he feels ready to cash out his shares and spend the rest of his life on an island in the South Atlantic Ocean?

Yet another way that Mad Men defers the Robbins question is by placing Peggy outside the maw of advertising—making her situation so riddled by sexism that we sympathize too much to worry if she is becoming another suit. At the end of last season with Don on the ropes, Peggy looked to be taking her mentor’s place, pantsuit and all. Instead it is Lou who has played the part of the Man in Season 7, while Peggy has struggled with a moribund love life and undermined confidence. Last week Pete—against the ironic backdrop of his own domestic dysfunction—persuaded Peggy to let Don do his magic. As a woman, Pete told her, she must stand for a maternal presence even though the only child in her life is her young neighbor Julio. This week, watching her hold up two outfits for Julio’s advice—a grey color that “men wear” and a stripey number that is “pretty” but may make her sweat—we know that there is no winning choice for Peggy. Chafing against a clueless stereotype of femininity, her only recourse is to suck it up.

The upside of this lapse of confidence on Peggy’s part is the return of Don as avuncular mentor. I must confess that I am a complete sucker for this aspect of the Draper persona. The genius of this character is that he is sometimes quite believably the professional woman’s friend: an icon of alpha male confidence that a woman like Peggy can simply summon before her as though he were the working gal’s answer to Barbara Eden in a bottle. It helps that the Don of Season 7 has so far been a recovering Lothario. Not since Neve Campbell propositioned him in the premiere have we sensed that infidelity is very much on his mind. (We can’t count the threesome with Megan’s friend in “The Runaways” since that was her idea). Indeed, so chaste has Don become that, in another homage to the past, this one parodic, Don’s daffy secretary takes matters in her own hands and offers herself as solace for his troubles. The scene takes us back to a rather more successful secretarial seduction in Season 4 when Megan persuaded her boss that she could be discreet. In that episode, alcohol played a role in prompting Don to take the risk (and be unfaithful to Faye Miller). But the Don of Season 7 has come back from his Elba with womanizing and heavy drinking seemingly a thing of the past.

Not only the heart of “The Suitcase,” but also of the entire 3-season arc that preceded it, Don’s bond with Peggy has always been one of the show’s most compelling setpieces. Far be it from me to spoil the fun. Ah, but, Mad Men, Mad Men are there no moonshot stories we wish to pitch before releasing Don and his friends from Purgatorio? Whether embodied by Don, Freddy Rumsen, Ted, Peggy or that Mad Man Behind the Curtain, Weiner himself, are we really ready to declare that The Writer For Our Times is some good-enough cross between Walter Benjamin’s “The Storyteller” and the crooner in a Hollywood musical? (Bert’s posthumous appearance in a song-and-dance number—a hodge-podge of meat and pasta if ever there was one—is the episode's biggest reveal: the final referent for “Waterloo” is not Napoleon, it’s Abba!) My point is not that the best things in life aren’t free. Nonetheless, in taking the occasion of a “giant step for mankind” for a clever pastiche about Mad Men’s own history, the show missed the opportunity to make JFK’s determination to get to the moon by the end of the 1960s meaningful for our times.

Yes, there were doubtless many back then who noted (like Neil and Sally) that the government’s quixotic Cold War extravaganza was costing billions of dollars sorely needed on Earth. But what Mad Men did not pause to contemplate was how few people at the time rejected the possibility of fighting Communism, a War on Poverty, and exploring the final frontier all while expanding affordable higher education. For both better and worse—on behalf of many regrettable causes as well as good ones--these were times when Republicans like Richard Nixon (or Henry Francis) shared the basic liberal premise that the purpose of government is to do all the things that individuals cannot do and markets will not do. Missed, therefore, by Mad Men last night was the chance to refract the stifled aspirations of our own times. Frozen in a neoliberal austerity regime, we are assured that we can no longer shoot for the moon—not for renewable energy, affordable education, universal healthcare, or any other public good. Thus, the great story behind every ad today is not (or not only) our craving for lost connections; it's the never-ending neoliberal story that, give or take a few Middle East invasions, drone strikes, and ambitious surveillance programs, government’s job in the twenty-first century is to do the bidding of Job Creators.

When Don tells Sally she should not be so “cynical,” we sense he is right. But what kind of moon should we shoot for, daddy? Watching Mad Men last night, I longed for a crazy coot like Season 3’s Conrad Hilton to give us some glimmer of what the moon is for. What I got instead—Bert in a scene from the 1950s-meets-Mama Mia!—may well be the next best thing. But if “Waterloo” was not quite penned in the dead language of late capitalism, it was the vision of a show already convinced that the best thing to come from our turn-of-the-millennium is the advent of serial television.