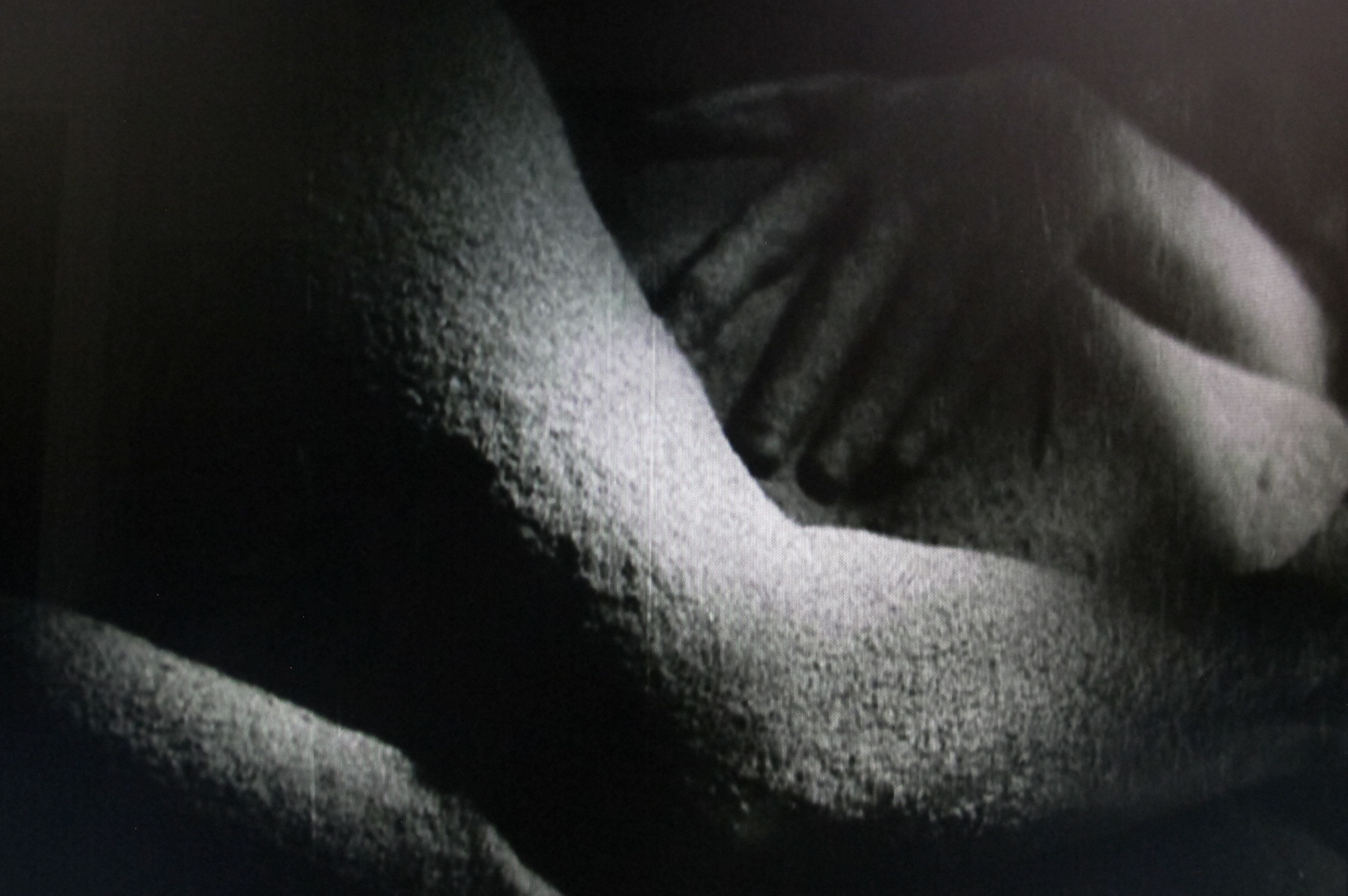

[On February 3, 2020 the Unit Criticism and Interpretive Theory hosted a Distinguished Faculty lecture "Nine Days of One Year: Soviet 1960s Cinema and the Nuclear Catastrophe" by Professor Lilya Kaganovsky (Slavic, Comparative Literature, and Cinema and Media Studies). Below is a response by Professor Brett Kaplan (HGMS/CWL).] Response to Lilya Kaganovsky's lecture "Nine Days in One Year: Soviet 1960s Cinema and the Nuclear Catastrophe" Written by Brett Kaplan (HGMS/CWL) Loose hips, bare feet, a slight slouch, flashback, close-up, the long pan, the fish-eye lens: Soviet thaw cinema, as Lilya describes it, exercises bodily and cinematic means in the wrestle to bring to the fore the saturation by the past of the present. The new bodily freedoms reflect a kind of liberation in tension with the shackles to multiple traumatic pasts: the Holocaust, the Atomic bomb, the vast numbers of Soviet dead in WW II. The fragmentations, the montages, the temporal disjunctions that often accompany this cinema speak to the struggle to convey traumatic events. As Lilya phrases it, her story is about “the relationship between WWII, the Holocaust and nuclear catastrophe that has yet to be articulated for Soviet cinema.” By gazing back at the eyes of Auschwitz and the complicities of witnessing, Lilya’s work articulates those interconnections for this 1960s cinematic moment. “The eyes of Auschwitz,” she says, “implicated the viewer, reminding them that besides Nazi concentration camps there were also Soviet prison camps and besides the cult of Hitler, there was also the cult of Stalin.” We might add, taking our cue from Romm’s understanding of the persistence of the past in the present, besides Soviet prison camps there are also, on our Southern border, right now, camps to detain immigrants; off the coast of Cuba a Naval Base holds prisoners without trial; we witness extra-judicial killings of foreign generals; and our president has just effectively been absolved of all crimes, without a trial, without witnesses, without evidence. Indeed, we might now, again taking our cue from the persistence of the past in the present see with Romm how “despite the fall of the 3rd Reich, fascism as a concept has not been defeated.” We see everywhere, from the goose-stepping Heil Hitler saluting white supremacists at Charlottesville to the guy in California who filled his front yard with a massive concrete swastika to the adoration for Trump and complete absence of resistance from within the Republican party two days before he will doubtless be acquitted echoes of Hitlerian fascism. While as William Connolly and others have argued, these resonances are undeniable, important differences must of course be maintained. As Elaine Scarry brings to our attention in Thermonuclear Monarchy, Nixon, at the Watergate hearings, asked his lawyer to present him as “absolute a monarch as Louis XIV… and…not subject to the processes of any court in the land.” Scarry demonstrates in terrifying detail the absolute nature of the power a U.S. president has over mass nuclear destruction, the disinterest in listening to other nations who may argue against our vast nuclear arsenal and the ease with which it can be activated. The past does not repeat. It lives and moves with its loose hips and bare feet and comes back at us through the indelible montage of the traumatic flashback. Romm’s Nine Days of One Year appeared three years after a film that both influenced it and shaped it through reaction-formation. Both films tell the story of love triangles. In Romm’s text all the lovers exist simultaneously in the then-present whereas in Resnais’s Hiroshima mon amour the love triangle evolves in multiple temporal dimensions. In the present of the film, 1957, Elle (Emmanuelle Riva), is a French actress who fell in love with a German soldier during World War II and Lui (Eiji Okada) is a Japanese architect marked indelibly by the U.S. bombing of Hiroshima/Nagasaki. While in the present the actress and the architect have an affair in Hiroshima, the German lover becomes the third stretch of the love triangle. The backdrop revolves around Elle’s performance as a nurse in a film about the bombing so we see mediated reproductions of the victims of the bomb. Very much like the direct addresses Lilya discusses, Resnais includes scenes where “victims” (or rather, actors playing victims) stare directly at the camera, challenging us to see the effects of nuclear catastrophe, challenging us to not turn our gazes away in disgust. The architect draws out the memories of the past story of complicity and love between the French actress and the German soldier as the current lovers play out their present through their pasts and superimpose one upon the other ceaselessly.  The very structure of the famous and enduring image of the entwined bodies of the lovers near the beginning of Hiroshima mon amour insists on a turning of victimization into something else: ashes into sweat, memory into stark present. Cathy Caruth, through reading Derrida and Freud, locates “a history that burns away the very possibility of conceiving memory, that leaves the future itself, in ashes” (2013, 81). The stunning image of the ashed lovers functions as an apt metaphor for the “burning up” of memory itself in the aftermath of catastrophe and as the image threads its way through our imaginaries it provides a space through which to unpack the indelible nature of memory as trace. The striking images of the couple’s embrace set the scene for the film’s exploration of memory and victim and perpetrator traumas by rendering the lovers as almost indistinguishable; race and gender disappears, initially, as they hold each other, encased in ash. As they embrace, something gently falls on them, encrypts them, isolates them from their surroundings but simultaneously embeds them in their respective histories. Even though Duras specifies that the two should be “racialement, etc., éloignés le plus qu’il est possible de l’être” (1960, 11) the racial difference between them remains unstable, and the ash visually erases their shared trauma. If, for Derrida, ash becomes the paradigm for the trace, we can see how this image becomes the paradigm for memory as Hiroshima mon amour unspools its threads and rejects an either/or memory or forgetting when it is a question of traumatic pasts. The film revisits this powerful scene by cinematically underscoring this very superimposition many times, including the catalyzing moment when a traumatic flashback metamorphoses the hand of the Japanese lover into the hand of the dead German soldier, and the intercutting of the traumatic landscapes of Nevers and Hiroshima. Lilya points out that Romm found Hiroshima mon amour’s “juxtaposition of the burnt bodies of the victims of Hiroshima with those of the two lovers distasteful and offensive” but that he also adapted the films “magnificent lessons in montage.” The magnificence of the montage in Hiroshima mon amour happens through the temporal and aesthetic shifts between the present moment, saturated with coming to terms with the bombing, and the past, during the war, saturated with love for an enemy soldier, a soldier implicated in if not avowedly a supporter of the Nazi genocide. Invited to make a feature-length film about the bombing of Hiroshima after his groundbreaking early Holocaust documentary Nuit et Brouillard (1955), which expanded the international scope of Holocaust memory, Resnais famously struggled; only when Duras agreed to write the script did the project soar. Duras was brought in to the scripting of Hiroshima in order not to remake Nuit et Brouillard into a film about the atomic bomb. Thus, as Lilya explains Romm’s stacking of the Holocaust with the bomb with the war, we see can just catch the nearly invisible trace of Nuit et Brouillard on Hiroshima. The ashes at the beginning of the film, then, metaphorize both the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and carry the trace of the ashes of the crematorium during the Nazi genocide. Becoming more and more convinced that one could not make a documentary about the bomb, Duras’s script was meant to be a “love story…in which the atomic agony would not be absent” (Armes, 1968, 66). This entwinement in ash gives way to the bodies covered in sweat that then yields to successively clear bodies. Lovers emerge from the ash as if filming Pompeii backwards. Resnais notes that “Dans Hiroshima, le début n’est pas seulement une représentation du couple, c’est une image poétique. Et la cendre sur les corps, ça ne se réfère à aucune réalité anecdotique, c’est une pensée” (1960, 938). The poetic image, the thought (pensée) that Resnais imagines here, is expressly not meant to refer to any identifiable “real” and yet it affectively carries the weight of the bomb, the Shoah, and the memoryscapes of impossible pasts. The intense proximity of the pair makes it initially impossible to separate the bodies because the film equally gazes at them through the ash as victims but this common victimization changes polarities throughout, thus visually underscoring the film’s eschewing of any simple assumption of innocence and guilt. Hiroshima mon amour thus employs the language of ash to demonstrate the aftereffects of war on those aligned with victimization and perpetration. When Hiroshima mon amour was set the expectation would have been that everyone who survived the U.S. bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki would carry (literally) in their bones radiation and figuratively the ineradicable past nuclear catastrophe; but they might also be weighed down by the fear of a possible future apocalypse.[i] It remains unclear, because we are not granted much of his consciousness, whether the Japanese architect in Hiroshima mon amour suffers from PTSD or stoically moved on from his experience of victimization, perhaps because that experience was shadowed by his role in fighting with the Axis powers? This remains an open, intriguing question that the film staunchly refuses to answer. The voice-offs that inaugurate the dialogue and dialectical nature of Hiroshima mon amour offer a long series of negations that speak to the impossibility of witnessing and/or fully remembering the experience of victimization. As Elle’s voice-off claims to see the hospital at Hiroshima, the image discloses people in the hospital looking directly at the camera so her claim on vision becomes deflected back at the unnamed hospitalized injured. She then asserts that she saw the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum four times, as if the layering of visits could turn her into a witness. But Duras also has Elle observe keenly the way that the visitors to the museum imbibe these reconstructions. By thus reminding us of the mediations of memory, Duras and Resnais underscore the memory of nuclear catastrophe that goes beyond individual psyches: thus, that Elle could not have remembered directly is evident—she was in France at the time the U.S. bombed Hiroshima, but that she remembers in a more global sense is also underscored. In other words, the structure of the negations explains the unstable nature of postmemorial witnessing. By issuing these negations Duras and Resnais highlight the inherent impossibility of true witnessing, all we can do is embrace under the rain of ash. As Primo Levi famously asserted “we, the survivors, are not the true witnesses”—only those who perished in the worst can be said to be witnesses and this assertion met by negation puts this truth into play (2004, 63). Lilya argues that in Nine Days of One Year the differences between “the scientific methods of Nazi Germany and the development of the atomic and nuclear weapons (not only by the US but also by the USSR)” effectively dissolve and that there is “no moment in which science could be turned back or used only for good.” Lilya’s work powerfully illuminaties the shadows of the past as they emerge through the luminosity of Romm’s films and situates this temporal loosening within the larger questions at play: how can we adapt to the speed of our own scientific discoveries without destroying our planet and how can we find the traces of the past to avoid treading too closely with our loose hips and bare feet in its often treacherous pathways.

The very structure of the famous and enduring image of the entwined bodies of the lovers near the beginning of Hiroshima mon amour insists on a turning of victimization into something else: ashes into sweat, memory into stark present. Cathy Caruth, through reading Derrida and Freud, locates “a history that burns away the very possibility of conceiving memory, that leaves the future itself, in ashes” (2013, 81). The stunning image of the ashed lovers functions as an apt metaphor for the “burning up” of memory itself in the aftermath of catastrophe and as the image threads its way through our imaginaries it provides a space through which to unpack the indelible nature of memory as trace. The striking images of the couple’s embrace set the scene for the film’s exploration of memory and victim and perpetrator traumas by rendering the lovers as almost indistinguishable; race and gender disappears, initially, as they hold each other, encased in ash. As they embrace, something gently falls on them, encrypts them, isolates them from their surroundings but simultaneously embeds them in their respective histories. Even though Duras specifies that the two should be “racialement, etc., éloignés le plus qu’il est possible de l’être” (1960, 11) the racial difference between them remains unstable, and the ash visually erases their shared trauma. If, for Derrida, ash becomes the paradigm for the trace, we can see how this image becomes the paradigm for memory as Hiroshima mon amour unspools its threads and rejects an either/or memory or forgetting when it is a question of traumatic pasts. The film revisits this powerful scene by cinematically underscoring this very superimposition many times, including the catalyzing moment when a traumatic flashback metamorphoses the hand of the Japanese lover into the hand of the dead German soldier, and the intercutting of the traumatic landscapes of Nevers and Hiroshima. Lilya points out that Romm found Hiroshima mon amour’s “juxtaposition of the burnt bodies of the victims of Hiroshima with those of the two lovers distasteful and offensive” but that he also adapted the films “magnificent lessons in montage.” The magnificence of the montage in Hiroshima mon amour happens through the temporal and aesthetic shifts between the present moment, saturated with coming to terms with the bombing, and the past, during the war, saturated with love for an enemy soldier, a soldier implicated in if not avowedly a supporter of the Nazi genocide. Invited to make a feature-length film about the bombing of Hiroshima after his groundbreaking early Holocaust documentary Nuit et Brouillard (1955), which expanded the international scope of Holocaust memory, Resnais famously struggled; only when Duras agreed to write the script did the project soar. Duras was brought in to the scripting of Hiroshima in order not to remake Nuit et Brouillard into a film about the atomic bomb. Thus, as Lilya explains Romm’s stacking of the Holocaust with the bomb with the war, we see can just catch the nearly invisible trace of Nuit et Brouillard on Hiroshima. The ashes at the beginning of the film, then, metaphorize both the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and carry the trace of the ashes of the crematorium during the Nazi genocide. Becoming more and more convinced that one could not make a documentary about the bomb, Duras’s script was meant to be a “love story…in which the atomic agony would not be absent” (Armes, 1968, 66). This entwinement in ash gives way to the bodies covered in sweat that then yields to successively clear bodies. Lovers emerge from the ash as if filming Pompeii backwards. Resnais notes that “Dans Hiroshima, le début n’est pas seulement une représentation du couple, c’est une image poétique. Et la cendre sur les corps, ça ne se réfère à aucune réalité anecdotique, c’est une pensée” (1960, 938). The poetic image, the thought (pensée) that Resnais imagines here, is expressly not meant to refer to any identifiable “real” and yet it affectively carries the weight of the bomb, the Shoah, and the memoryscapes of impossible pasts. The intense proximity of the pair makes it initially impossible to separate the bodies because the film equally gazes at them through the ash as victims but this common victimization changes polarities throughout, thus visually underscoring the film’s eschewing of any simple assumption of innocence and guilt. Hiroshima mon amour thus employs the language of ash to demonstrate the aftereffects of war on those aligned with victimization and perpetration. When Hiroshima mon amour was set the expectation would have been that everyone who survived the U.S. bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki would carry (literally) in their bones radiation and figuratively the ineradicable past nuclear catastrophe; but they might also be weighed down by the fear of a possible future apocalypse.[i] It remains unclear, because we are not granted much of his consciousness, whether the Japanese architect in Hiroshima mon amour suffers from PTSD or stoically moved on from his experience of victimization, perhaps because that experience was shadowed by his role in fighting with the Axis powers? This remains an open, intriguing question that the film staunchly refuses to answer. The voice-offs that inaugurate the dialogue and dialectical nature of Hiroshima mon amour offer a long series of negations that speak to the impossibility of witnessing and/or fully remembering the experience of victimization. As Elle’s voice-off claims to see the hospital at Hiroshima, the image discloses people in the hospital looking directly at the camera so her claim on vision becomes deflected back at the unnamed hospitalized injured. She then asserts that she saw the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum four times, as if the layering of visits could turn her into a witness. But Duras also has Elle observe keenly the way that the visitors to the museum imbibe these reconstructions. By thus reminding us of the mediations of memory, Duras and Resnais underscore the memory of nuclear catastrophe that goes beyond individual psyches: thus, that Elle could not have remembered directly is evident—she was in France at the time the U.S. bombed Hiroshima, but that she remembers in a more global sense is also underscored. In other words, the structure of the negations explains the unstable nature of postmemorial witnessing. By issuing these negations Duras and Resnais highlight the inherent impossibility of true witnessing, all we can do is embrace under the rain of ash. As Primo Levi famously asserted “we, the survivors, are not the true witnesses”—only those who perished in the worst can be said to be witnesses and this assertion met by negation puts this truth into play (2004, 63). Lilya argues that in Nine Days of One Year the differences between “the scientific methods of Nazi Germany and the development of the atomic and nuclear weapons (not only by the US but also by the USSR)” effectively dissolve and that there is “no moment in which science could be turned back or used only for good.” Lilya’s work powerfully illuminaties the shadows of the past as they emerge through the luminosity of Romm’s films and situates this temporal loosening within the larger questions at play: how can we adapt to the speed of our own scientific discoveries without destroying our planet and how can we find the traces of the past to avoid treading too closely with our loose hips and bare feet in its often treacherous pathways.