On October 11, 2022, Cameron McCarthy spoke at the Unit for Criticism on “The Postcolonial Imagination: Tools for Conviviality.” Beginning with his own high school education in Barbados, McCarthy used the school’s entrance examination system and literary curriculum—both determined in England and centered on an English canon—as an entry point into his broader questions about postcolonial art and aesthetics. He defined postcolonial theory as the “practices of systematic reflection on dominant relations, produced in the process of elaboration of colonial and neocolonial relationships and encounters between metropolitan countries of the West and the third world”—relationships that are properly understood as center-periphery, overdetermined, and reciprocal relationships. Positing that postcolonial art is itself theoretical and philosophical, and that it acts as a precursor to theory, he further argued that separating the third world from the first world fails to illuminate postcolonial art. Postcolonial art and aesthetics are distinct in that they engage with the first world over issues such as identity, authority, freedom, and rights. Postcolonial art and aesthetics are therefore a “powerful critique of overmastering authority of the self-sufficient subject and hegemonic relationship” in the hierarchy of discourse. It must be understood as double- and triple-coded, with multiple layers and affiliations, and fragmentary in conveying emancipatory and utopic visions.

With this understanding of postcolonial art and aesthetics, McCarthy posed the following working questions:

- Can postcolonial art objects and aesthetics support the scrutiny of a form of critical analysis grounded in ethnographic evaluation and social thickness?

- What theories and practical purchase might such an evaluation yield, assuming that third world cultural forms are not bastardized texts of first world arrangements?

To address these questions, McCarthy looked to a number of postcolonial exemplars, such as novelists, poets, and painters, from the Global South and the periphery of the metropole. He played “Columbus Lied” by Shadow and screened a slideshow of paintings from his “Global Perspectives in Curriculum” to illustrate how, in responding to European art, the “cultural circle of reproduction is never complete.”

Following this example, McCarthy briefly traced the history of critical concerns about art’s function in Western Marxism, citing Karl Korsch’s “Why I am a Marxist,” György Lukács, and Raymond Williams. He further discussed the Frankfurt School’s schism on aesthetics: where Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer understood modern art to be compromised by industry and unable to critique and instruct, Walter Benjamin and Bertolt Brecht argued that art under mechanical reproduction offered possibilities for democratic expression and subaltern transgression. McCarthy argued that it is necessary to think beyond this divide and explore how postcolonial art leads to new understandings of past, present, and future in neoliberal and global contexts. Art thus does the work that theory does to question “received genres of experience, aesthetic traditions, and contemporary, political, and social life” and rethink center/periphery relations.

Postcolonial art, therefore, rewrites the Marxist base/superstructure model, refusing the top-down models from “Marxist, overwrought ethnographies and mainstream social sciences” and raising the status of aesthetics. In working against binaries, postcolonial art points to themes of community, interdependence, and cultural transition. This is why postcolonial artists are able to anticipate postcolonial theory. Postcolonial art’s meanings and theories depart from modern and postmodern theory, offering the following possibilities:

- A critique of hegemonic realism

- Double- and triple-coding

- Emancipatory visions

Hegemonic realism, McCarthy says, foregrounds what Catherine Belsey calls “a hierarchy of discourses,” which places a freestanding subject in the center of the work, such as in the painting of “The Ambassadors” by Hans Holbein the Younge.

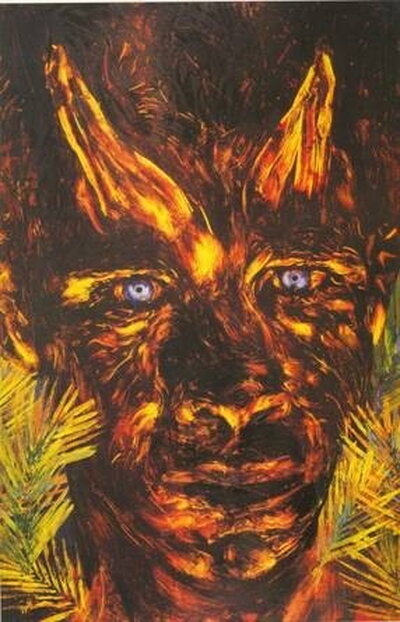

Postcolonial artists respond to this hegemonic realism by deflating characterization and displacing “overmastering narrative subjectivity,” thereby destabilizing claims to authority over knowledge and elevating the status of agroproletarian characters. By centering the people that colonial narratives have marginalized, McCarthy argued, postcolonial artists place the colonized and the colonizer in the same space and attempt to reintegrate oppositional interests and desires. As an example, Arnaldo Roche-Rabell’s painting “Poor Devil” reflects the politics of identity and anticolonialism in Puerto Rico, portraying a blue-eyed devil as a folk on the face of an Afro-Caribbean man. McCarthy positions this painting in the context of a broader search for identity as a search for a collective self.

McCarthy ended his talk by turning to the role of postcolonial artists as theorists whose contemplations place art at the center of struggle for happiness, sustained possibility, and community in the “tumult of globalization in the twenty-first century.” Postcolonial art therefore poses identity and the future as “open grounds of possibility and negotiation” that “allow a glimpse of a hopeful future,” responding to a need for dialogue in the multicultural twenty-first century.