[On Tuesday, October 6, 2020, Dr. Alexander G. Weheliye presented a lecture on Biopolitics as part of the Modern Critical Theory Lecture Series. Below is a response by Austin Hoffman (Anthropology, UIUC)]

Black Feminism and the (Re)Making of Biopolitics

Written by Austin Hoffman

“Traveling theories, particularly those supposedly transparent and universal soldiers in Man’s philosophical army, should be exposed to and reconstructed…with a critical consciousness that probes the conceptual constraints of these theories, especially as it pertains to the analysis of race and exhumes their historico-geographical affectability.”

So claims Alexander G. Weheliye in his 2014 book Habeas Viscus . The two primary universal soldiers Weheliye aims to expose and reconstruct in this text are Michel Foucault’s conception of biopolitics and Giorgio Agamben’s theorization of bare life. A revisitation of these arguments would be a main topic of Weheliye’s presentation on biopolitics for the 2020 Modern Critical Theory lecture series.

The lecture began with an explication of Agamben’s figure of the Homo Sacer or sacred man, which is banned from the political community and barred from the category of the human. This understanding is derived from the ancient Greek distinction between bios and zoe; the former is incorporated into the polis and allows for full human existence, whereas the latter is mere biological substance, essentially naked or “bare life.” Here Agamben builds upon Foucault’s understanding of how modern power operates, stated most explicitly in his 1975-1976 lecture series “Society Must Be Defended” and subsequently in The History of Sexuality . As opposed to sovereign and disciplinary power which directs itself at the individual or “man-as-body,” modern power shifts to the governance and management of the population or “man-as-species.” Foucault summarizes this in his proclamation that “The right of the sovereign was the right to take life and let live. And then this new right is established: the right to make live and to let die.”

While inspired by the concept of biopower, Agamben believes Foucault does not fully elucidate how sovereign and modern forms of power are imbricated. He pursues a corrective to Foucauldian biopower—and here he is also engaged in dialogue with Walter Benjamin and Carl Schmitt—via the insertion of Homo Sacer, claiming that bare life is entrapped within a Schmittian “state of exception” or a suspension of law which relegates it to abandonment and death. Homo Sacer is the referent for the state’s exercise of biopower and forms the core of political modernity, and, as Weheliye explains, Agamben imagines the field of bare life eradicating all lines of distinction along the axes of race, gender, religion and nationality.

For Agamben, the Nazi concentration camp is the quintessential theatre of this political arrangement and the erasures of racial hierarchies and identities which it entails. After unpacking how the concentration camp operates in Agamben’s thought, Weheliye begins to interrogate the concerning occlusions of race embedded in the philosopher’s universalizing assertions, which become particularly evident in his writing on the musselman. This is an antiquated and derogatory German word for Muslim men, specifically those within concentration camps. Weheliye, referencing Agamben’s Remnants of Auschwitz , expands upon the positioning of the musselman as the most intense embodiment of bare life and human degradation, one which “transcends race” and produces a “final biological substance.” Pausing to contemplate this, Weheliye asks of Agamben--and by proxy Foucault—what is this desire for such a figure to transcend race? Why is this necessary in their respective works? He responds to the instrumentalization of the musselman with another question: how can racism, biopolitical or otherwise, exist without race? Weheliye’s argument is that even if the musselman is biological substance, he is an unavoidably racialized one; his ontological status does not exceed race, but rather epitomizes it.

From here Weheliye transitions to levying a similar critique directly at Foucault. He argues that race and colonialism rarely take center stage in Foucault’s project, mostly floating clumsily and uncritically at the periphery of his thought or not at all. These omissions are particularly glaring in The Order of Things , in which Foucault investigates the invention of European “Man” in the Enlightenment, yet does not consider how racism and colonialism directly undergird and enable this invention. Foucault also heavily privileges Europe and the historical caesuras within its populations. In a moment of personal reflection, Weheliye remarks on his experience as a Black German, and how nonwhite Germans are always already removed from Germanness. He sees this sentiment conceptually reflected in mainstream biopolitics.

Like Agamben, Foucault frequently uses Nazism as a paradigmatic example to demonstrate his ideas, but does not substantively examine how the biopolitical technologies of the Third Reich are deeply entangled with the genocidal Western regimes that predated it in Africa, Asia, and the Americas. The Nazis did, after all, draw direct inspiration from Jim Crow and the genocide and elimination of Indigenous peoples in the United States.

As a partial solution to these occlusions, Weheliye points to the work of Achille Mbembe, who introduces an analysis of racial apartheid and slavery into biopolitics with his theory of “necropolitics.” To be clear, Weheliye does not advocate for a simple substitution of the plantation or reservation for the concentration camp, but rather to think about the relationalities between these sites without resorting to easy comparisons and analogies. He also encourages us to consider the more benign and quotidian instances of social control which are potentially overshadowed by spectacular forms of episodic violence.

Weheliye’s nuanced response to this biopolitics of whiteness is most directly indebted to the work of Black feminist scholars such as Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Hortense Spillers, and Sylvia Wynter. The ideas of Spillers and Wynter in particular were foundational to Habeas Viscus, where Weheliye says that “[their] reconceptualizations of race, subjection, and humanity provide indispensable correctives to Agamben’s and Foucault’s considerations of racism vis-à-vis biopolitics.” Weheliye juxtaposes Agamben’s bare life with Spillers’s idea of “hieroglyphics of the flesh,” which theorizes how the Black body was dehumanized and ungendered during the Middle Passage, reduced to mere flesh as opposed to a body with legal personhood; this is a transformation into pure biological substance unique to the Black experience, one defined by a process of racialization rather than transcendent from it. Spillers contends that these hieroglyphics transfer across generations, thus demonstrating how the marking, branding, whipping, and other tortures of chattel slavery constitute both a physical and an ontological maiming.

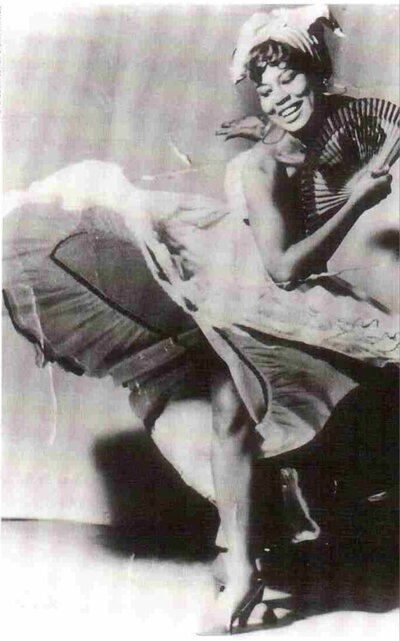

"Sylvia Wynter, Rome, 1950s. Photo provided by Sylvia Wynter and printed in David Scott's The Re-Enchantment of Humanism."

Sylvia Wynter—who was the subject of several questions during the Q&A portion—is also acutely concerned with the invention of modern man and its tiers of race, but approaches this from a resolutely decolonial lens. Her decades-long intellectual project is an extended genealogy of humanism, detailing a series of epistemic breaks in European man’s “descriptive statement” or governing logics of being. She argues that the historical shift from a theological or “theocentric” mode of self-understanding to a rational or “ratiocentric” one produced a new genre of humanism which naturalized white supremacy not on the basis of God’s divine will but rather from a secularized bio-evolutionary standpoint. This version of white humanism has come to stand-in for the whole of our species. Weheliye then expounds upon Wynter’s work, saying that racism is not merely wrong ideology; it has been so deeply sedimented through a multiplicity of mechanisms that it manifests physiologically. He connects Wynter’s understanding of race to rampant cases of police terror. The murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, among countless others, are deemed justified or natural to many because this has been encoded into our neurochemical reward systems. This echoes Wynter’s reflections on the 1991 Rodney King beating that she expressed in an open letter to her colleagues.

"Zakiyyah Jackson's Becoming Human, just out from NYU press, is also inspired by Wynter and Spillers, among other Black feminist scholars."

The takeaway from Weheliye’s reading of Black studies against the grain of biopolitics is that scholars in the vein of Wynter and Spillers provide alternate genealogies for theorizing hierarchized categories of the human species in western modernity. Contra Foucault and Agamben, they do not sideline race and gender, but instead expose how they are, as Weheliye put it, “the flesh and bones of modern man.” Another Black feminist thinker in this tradition is Zakiyyah Iman Jackson, whose new book, Becoming Human examines the fraught intersections between Black studies and posthumanism. Weheliye greatly appreciates her drawing attention to contemporary discourses of genetics and epigenetics. Jackson is concerned that while epigenetics unsettled racist theories of biological reductionism, it may still be interpellated by antiBlackness. She takes the example of high infant mortality rates in Black mothers, which remain consistent even among those with advanced degrees and in higher income brackets. This shows that despite popular scientific conceptions, socioeconomic stability is a necessary but insufficient condition for combatting antiBlackness.

Other questions posed from the audience asked about the usefulness of other thinkers who work with theories of biopolitics like Mbembe and Ann Stoler, and the racial logics at play in both neoliberal and former Soviet states. While Weheliye does not discourage scholars from engaging with biopolitics, he commented that he is unsure it can help us fully understand how race operates outside of the European context, and cautions us to be wary of how the uncritical celebration of Agamben and Foucault in the U.S. academy may smuggle in forms of racial elision and antiBlackness. Here Weheliye would seem to agree with Jackson, who says in the coda of Becoming Human that, “we need not only the subversion of racialized codes but also the mutation of ordering logics and their structures of signification to forestall the reintroduction and dissimulation of racialized logics.”