[On Tuesday, September 15, 2020, Dr. Jeffrey T. Martin presented a lecture on Structuralism as part of the Modern and Critical Theory Lecture Series. Below is a response by Sabrina Yun-Che Lee (English, UIUC)]

Structuralism's Promise and Peril

Written by Sabrina Yun-Che Lee

In the half-century-long wake of poststructuralism, structuralism often seems merely a necessary foundation that will pave the way for more exciting and relevant theories. However, by grounding his discussion of structuralism within its historical context, Professor Jeffrey T. Martin explored its far-ranging effects and material impact on our world today.

Martin began his lecture by asking us to consider structuralism with “the eyes of a child,” to momentarily suspend our skepticism so that we could understand how thrilling this theory once appeared. With degrees in mathematics and anthropology, Martin asked us to consider structuralism as “a high-water mark of modernist faith in the mathematical structure of humanity.” He argued that structuralism was full of the promise of modernity—the promise that humanity would progress enough to finally understand the secret to the universe and crack the code underwriting all things. Martin anchored its origins in the scientific revolution and the turn away from a theologically centered understanding of the world in favor of one driven by science and rationality. These developments posited math as the language of God, a theory that reached its peak with the publication of Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead’s Principia Mathematica in 1910.

But, crucially, this form of thinking was not just about math or understanding the cosmos. Even as scientists and mathematicians extended its scope outwards in search of the key to the universe, other scholars turned its perspectives inwards in search of the key to humanity. During the early twentieth century, linguist Ferdinand de Saussure proposed the radical idea that language is not speech and that the meaningful dimension of language does not reside in noise but is made possible by a virtual structure outside of time governed by conventions and rules. Signs as units of written language are not autonomously meaningful; rather, meaning is made possible by a system of distinctions among sounds and concepts. In other words, a sign only gains meaning when understood in relation to other signs.

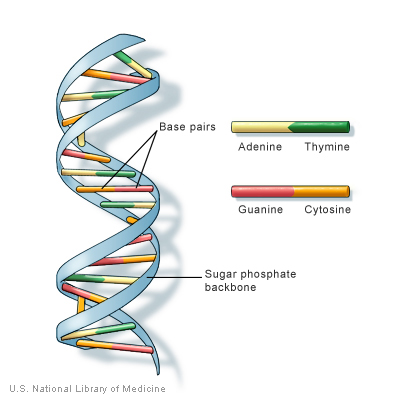

This compelling way of understanding language inspired anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss in the mid-twentieth century to apply this technique in order to understand culture. He saw structuralism as the way to decode human experience itself. For a structuralist, culture is not just experience. Instead, culture is like language: it is the system of differences that allows us to understand life as meaningful. This decoding process depends on discovering the fundamental units of difference—the binary oppositions—of whatever is under scrutiny in order to discover the system of differences that correlates with the structure of meaning. So, as Saussure focused on phonemes as the base units of meaningful sound in order to understand how language works, Lévi-Strauss focused on mythemes, the base units of culture distilled from practices or rituals, to understand the connections between experience and meaning. Martin explained that this same thought process can be seen in how we understand DNA as the building blocks of the genetic code or how computer language is composed of bits. Far from mere technicalities of an outdated theory, working with base units of difference in order to divine particular structures still suffuses much of our understanding and experience of the world today.

Just as structuralism disabuses us of any idea of divinely inspired language or transcendental experiences, it also figures humans not as creators in their own right, pulling ideas or masterpieces from thin air, but as bricoleurs or tinkerers. As Martin explained, bricolage is making do with what one has on hand. It’s like scavenging through the fridge to see what one might be able to cobble together. Yet, even though we live within structures, our actions aren’t necessarily predetermined; we don’t just repeat structures. Instead, we tinker, we play, we carry out “half-improvised rituals.”

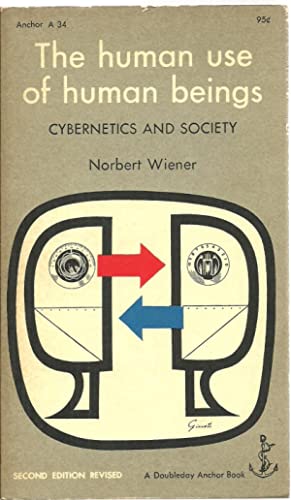

Martin concluded his talk by considering the dark side of structuralism and the problem with objectifying subjectivity. Structuralism’s quest for the key to everything was driven by a desire to control, and alongside the stories of Saussure and Lévi-Strauss runs a parallel story in which academics, business leaders, military officials, and police officers operationalize the idea that scientific and technological thinking can be used to understand the human psyche in order to manage society. For example, “brainwashing” and its attendant tortures, as well as surveillance capitalism, have been rationalized and made plausible through structural thinking. It is for reasons such as these that Martin warns against furthering the mission of structuralism. But these same reasons also demand a thorough and urgent understanding of structuralism so that we may be better equipped to combat such continuing atrocities.