[On October 1, 2019 Professor Marcus Keller (French & Italian) presented a talk on Deconstruction as part of the Modern and Critical Theory Lecture Series. Below is a response by Aidan Watson-Morris (English)] Marcus Keller's Hospitable Derrida Written by Aidan Watson-Morris (English) If the philosopher Jacques Derrida ushered in the end of truth, truisms about his work proliferate. His slippery style mirrors the movement of meaning or, less charitably, his tortuous texts generalize their own incoherence. Returning to his writing, we find ourselves surprised at the traces of a mind working hard to be understood: ideas patiently developed and illustrated through examples, signposted conclusions, and—most surprisingly—orderly, numbered lists of key points throughout. Rather than a radical skepticism about the possibility of meaning, perhaps it was Derrida’s strong desire to communicate that gave him the clarity to see language’s paradoxes. His playful style records not a resigned relativism but a new approach.

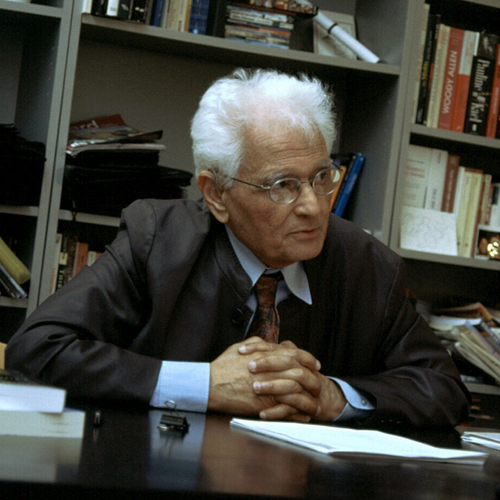

Photo of Jacques Derrida from an author page on Verso Books’s website.

Photo of Jacques Derrida from an author page on Verso Books’s website.

Marcus Keller’s recent Modern Critical Theory lecture did no disservice to Derrida, then, in its lucidity. Keller, French and Italian professor at the University of Illinois and author of Figurations of France: Literary Nation-Building in Times of Crisis, attended lectures by Derrida while studying at the University of California Irvine. Moving from a taxonomy of key concepts to a historical sketch of the philosopher, Keller offered deconstruction as a method and an ethical—no less political—attitude. As method, deconstruction is marked by caution, what Keller calls the “slow movement” of displacement. Ferreting out those suggestions of reassuring coherence—sources, essences, and binaries—deconstruction looks to what is “unthinkable” within a text and shows how it is in fact the very premise of the text. We can only think something present if its absence remains a possibility; destruction contains the trace of construction in its verbal DNA. Derrida’s oft-quoted claim that there is no outside-text refers to those apparent exclusions which, with care, we can find already inside the text. By looking at what seems to get left out, we find it was there all along. The tools deconstruction brings to this task are many, among which Keller focused on critical favorites. Différance undoes the clean structuralist divide between a word’s lexical form and semantic content. If the relationship between these is arbitrary, a word contains no positive content. Rather, all words are only their difference from other words, meaning that these seemingly absent terms are implicitly present. Nor can we find a content inside of these words, but only further deferral down the chain. This system of difference and deferral is the constant play of meaning. Derrida names the irreducible multiplicity of meanings dissémination, which is the condition of language. In order to signify an intent, any utterance must also be able to produce other meanings which exceed this intent. All language necessarily might “fail” to communicate an intent and communicate something else instead. Rather than a failure, Derrida suggests that these myriad possible meanings structure language itself, and the “successful” communication of an intent is a byproduct. Rather than an intent, Derrida finds aporias at the heart of a text, those irresolvable contradictions without which it could not exist. He searches for these through meticulous, respectful readings in which, for Keller, he models both an ethics of patience and a politics of difference. Among the aporias in Derrida’s Spectres of Marx, for instance, is the phantom of non-belonging haunting all nationalism.

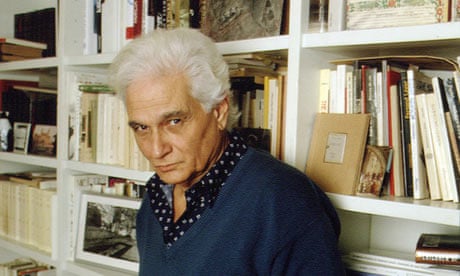

Photograph by Richard Melloul/Sygma/Corbis for The Guardian.

Photograph by Richard Melloul/Sygma/Corbis for The Guardian.

Derrida was himself familiar with this phantom. Born in 1930 in French Algeria to Jewish parents, he was expelled from high school during occupation and lost his citizenship for two years under the Vichy regime. Few conditions better underscore the precarity of presence-versus-absence than sudden statelessness. He saw himself as “a child of the margin of Europe,” informing his approach to philosophy “from a certain margin.” In this margin we find, lurking in the shadows of the text, a philosopher who upended the metaphysical tradition and a radical who carefully and lovingly read the canon. If Derrida’s interventions can feel insufficient, we might heed his caution. We step outside of an ideology at the risk of reproducing it; the means of critique are already there, on the inside, for those patient enough to find them.