[On Tuesday, November 10, Dr. Sean Metzger (Theater, Film & Television, UCLA) presented a lecture on Queer Theory as part of the Modern Critical Theory Lecture Series. Below is a response by Joe Coyle (Anthropology, UIUC)

Thinking Queer Theory Transnationally and Geopolitically

Joe Coyle (Anthropology, UIUC)

Sean Metzger’s Modern Critical Theory Lecture on queer theory traced important genealogies of the term “queer,” especially attending to the transnational as a vector for queer’s travels as theory, as commodity, and as difference. His presentation pushed for an understanding of queer that de-centers Euro-American contexts and epistemologies as the presumptive sites of queer knowledge production.

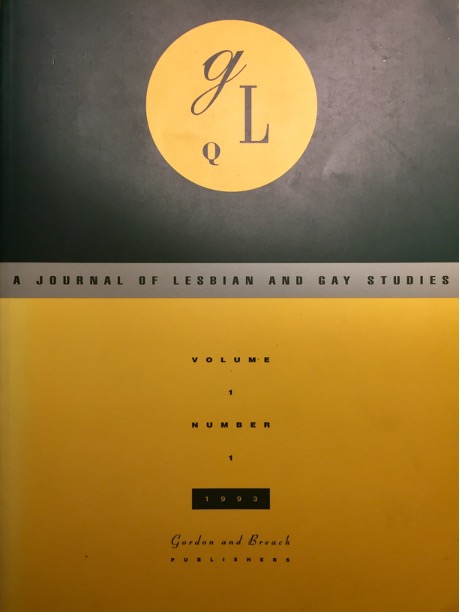

Metzger began by exploring one strand of queer theoretical production that has largely avoided the transnational, thereby naturalizing a global northernness. He situated the early work of Teresa de Lauretis and Judith Butler within this formation. Metzger identified Butler’s 1993 GLQ essay “Critically Queer” (and her prior work in Gender Trouble) as a major turn in the politics of feminism and the concept of queer. Appearing in the inaugural issue of GLQ, this work challenged the notion of the agential subject by attending to the ways social recognition precedes and conditions the formation of any subject. In this work, Butler develops the concept of performativity. Attempting to correct misreadings of her book, Gender Trouble, especially her discussion of the subversive potential of drag , Butler writes: “gender performativity is not a matter of choosing which gender one will be today. Performativity is a matter of reiterating or repeating the norms by which one is constituted” (22). Butler clarifies the performativity of queerness: “‘queer’ derives its force precisely through the repeated invocation by which it has become linked to accusation, pathologization, insult” (18). Because her reading of performativity challenges the self-determination of self-naming, Butler anticipates the critiques of queer that would follow, offering that “the critique of the queer subject is crucial to the continuing democratization of queer politics” (19).

Metzger paired Butler’s work in “Critically Queer” with Neville Hoad’s GLQ article “Between the White Man’s Burden and the White Man’s Disease” (1999) to attend to tensions in queer theoretical production concerning the transnational. While Butler doesn’t attend to discourses outside Euro-American traditions, Hoad considers the transnational production of lesbian and gay human rights discourses in a postcolonial South African context. Addressing the problem of the ostensible “universalism” of gay and lesbian human rights, he states that "these rights are extrapolated from a category called lesbian and gay identity, or, less specifically, 'sexual orientation,' which more often than not fails to map onto the bodily practices or more extensive worlding(s) of the subjects it promises to describe. Rights based on sexual orientation are also the newest particularity in the universalizing human rights legacy of the European Enlightenment" (561). On the other hand, he points out that South African cultural nationalist discourses appealing to tradition to make the case that homosexuality is a dangerous “Western import” disregard these effects on heterosexual practices: “Western cultural influence is equally pervasive in the wider ‘straight’ society…no one labels monogamous heterosexuality a decadent Western import, which, given the historical polygamy of many sub-Saharan societies, it may well be” (564).

Figure 1: Still from Pink Money performance

To build upon this analysis of queer’s transnational currency, Metzger screened a video segment of the South African queer performance group Pink Money. Pink Money as “performance, party and protest in one” exposes “pink dollar” tourism and discourses of eroticized African difference, interrogating the ways so-called “gay universalism” speaks through the colonial desire for commoditized difference. The clip opened with artist Anelisa Stuurman providing the Swiss audience with a taxonomy of South African lesbian identities, each identity conveyed as a different kind of alcoholic drink, which another Pink Money artist offers to those in the audience to consume. After the audience drinks South African lesbian difference, artist Kieron Jina narrates his experience of being harassed by men in a club in Basel, Switzerland. Jina describes navigating men looking at him like he was “juicy tropical fruit,” a sashaying Grindr match, and a man who calls him Sweet Nefertiti and “puts his knees into pee on the bathroom floor.” “Now I’m a germophobe,” Jina proclaims, “and an African Queen, and when I think about having sex I think of Egyptian white cotton sheets. YOU CAN DO BETTER! I dashed out of there, back to the dance floor... GIRLS! They’re trying to eat me here!” he yells as he runs to the dance floor to begin voguing with the rest of Pink Money

Figure 2 Still from Pink Money.

To bring into relief the way histories of transnational violence can also be the source of imagining queer diasporic connection, Metzger turned to Natasha Omise’ke Tinsley’s 2008 article “Black Atlantic, Queer Atlantic.” In an examination of relationalities that emerged at sea through the transatlantic slave trade, Tinsley reads shipmate relationships of enslaved Africans as queer: “Queer not in the sense of a "gay" or same-sex loving identity waiting to be excavated from the ocean floor but as a praxis of resistance. Queer in the sense of marking disruption to the violence of normative order and powerfully so: connecting in ways that commodified flesh was never supposed to, loving your own kind when your kind was supposed to cease to exist, forging interpersonal connections that counteract imperial desires for Africans' living deaths" (199). Tinsley examines the ways this history is drawn upon by the queer diasporic fictional literature of Maurine Lara and Dionne Brand to “harbor new routes to being, routes neither shielded nor boxed in by doors of hegemonic space, time, and identity” (211).

The final two pieces Metzger considered, Anjali Arondekar and Geeta Patel’s introduction to the GLQ special issue, “Area Impossible: The Geopolitics of Queer Studies” and Kirk Fiereck et al.’s “A Queering-to-Come” took “queer” to task by examining the geopolitics of certain queer theoretical imaginaries. In “Area Impossible,” Arondekar and Patel argue that the citational underpinning of queer theory was and continues to be drawn primarily from the United States. Moreover, they argue, when “invoking non-Euro-American sources, settings, and epistemes as exemplars, queer theory mostly speaks to US mappings of queer, rather than transacting across questions from different sites, colluding and colliding along the way” (152). By arguing for a renewed area studies approach to challenge these epistemological biases, they call for a broadened approach to empire that moves “beyond renewed assertion of US empire and US neoliberalism as the formative impetus for the politics of queer studies,” attends to geographically specific processes of racial formation, and practices a citational culture that does not retrench “particular hegemonic origin sites” of theory production (156, 157).

Figure 3 First issue of GLQ

From an African context, Kirk Fiereck, Neville Hoad, and Danai Mupotsa’s “A Queering-to-Come” addresses the geopolitics of queer theory by bringing to the fore “a usable past for both the lived experience and the study of African sexual subjects” and shows how “queer theory elaborated from Africa can inform queer theory’s Euro-American silent ethnocentrisms” (364). The authors propose the concept of the “African queer customary” to show how African sexual subjects inhabit customary practices in queer ways that “contest the secret normativities and ethnocentrisms of Euro-American queer studies scholarship, or even undo some of the heteropatriarchal norms of African ethnonationalisms” (368).

Metzger concluded his presentation by reflecting on the journal GLQ itself in relation to the transnational. If by the fifth issue of the journal there was a concerted effort to engage the transnational explicitly, Euro-American scholarly norms still shape its modes of knowledge production. The project of engaging forms of queerness that work against the internal norms and logics that comprise Euro-American queer theory remains a pressing concern and points to some of queer theory’s own limits.