[On Tuesday, September 8, 2020, Dr. Timothy Brennan presented a talk on Marx and Marxism as part of the Modern Critical Theory Lecture Series. Below is a response by Aidan Watson-Morris (English).]

Timothy Brennan’s New Marxist Materialism, Same as the Old

Written by Aidan Watson-Morris

Karl Marx’s claim that our thinking is historical, that ideas emerge or gain traction when material conditions allow, can be supported by the renewed enthusiasm for Marx himself, whose sales tend to spike in times of economic crisis. In the midst of our current crisis, many will likely turn again to the critique of political economy. For the precarious or simply curious, Timothy Brennan’s lecture on Marx and Marxism offered substantial returns.

Brennan’s influential, far-reaching body of work spans Marxism, postcolonial theory, world literature, phenomenology, and popular music, among other topics. His most recently published book is Borrowed Light, Volume 1: Vico, Hegel and the Colonies, and he has forthcoming work on “imperial form” and a biography of Edward Said. While he declined to identify himself as a partisan of a specific Marxist politics, he presented a clear, provocative vision of Marxism as an intellectual tradition that demands serious engagement.

Brennan’s lecture took two parts, divided by Q&A sessions, outlining the distinctive features of Marxist analysis before challenging elements of New Materialism as an ascendant theoretical mode. Brennan anatomized three key components of Marxist theory: it is particularly historical, understanding people and events as responsive to larger social structures; it is immanent, which is to say that it does not establish a priori ideals against which to measure its objects but works within their logic; and it is relatedly dialectical, which is to say that, rather than ignoring or rejecting (for instance) New Materialist thought, Brennan’s address signals respect and a desire to enter into conversation, to push further toward truth. Truth, for Marx, is understood not as an abstract or intellectual gesture, but a correspondence between concepts and material reality, as well as the potential to reestablish this correspondence when it fails.

By virtue of these features, Marxism remains vital for its historical reflexivity, which Brennan fully employed in his account of the US academy. Brennan’s lecture addressed itself partly as a dialectical response to academic trends that paved the way for the pluralism that brackets Marxism as a mere option on a menu of analytic frames. In an academic professional setting, anticapitalist critique fits best at the margin. For Brennan, the displacement of Marx in the US academy is a symptom of interwar anxieties about humanism’s political potential. The humanist tradition sought to improve collective life through action, a potential often activated in the anticolonial movements of the twentieth century. As well as being a politically pernicious maneuver, Brennan shows the academic sidelining of Marx to be a theoretical mistake that obscured the specific ideas with which certain approaches are in dialogue —poststructuralism, for instance, or New Materialism, Brennan’s primary interlocutor.

New Materialism, as Brennan points out, sounds quite a lot like Marx’s analysis in which material needs set the stage for our thought. Yet New Materialism challenges any materialism which foregrounds human actors. New Materialism questions the neat division of human actors, on the one hand, and the nonhuman world they act upon on the other. While Brennan did not argue that New Materialism is necessarily conservative in its outlook, he persuasively criticized its self-presentation both as new and as materialist. Tracing a continuity with an academic debt to Martin Heidegger and the humanities’ perennial desire to borrow prestige from the physical sciences beneath self-professed novelty, Brennan suggested that the New Materialism was not a historical materialism but a metaphysics which, by mystifying intent (and so intentional action), effectively results in a passive stance, what Brennan described as an antihumanist “romance with oblivion.” While admiring the New Materialist desire to move beyond social constructionism, Brennan showed the appeal of New Materialism for conservative thinkers (among his targets, Bruno Latour). Instead, Brennan suggested we attune to “the great unsaid” of the humanities: the human subject who makes their own environment, freighted by the weight of history.

If Marx uniquely endows the human subject with agency, he does so to question systems which alienate and exploit the subject, like capitalism. Shifting the ground of agency so as to dissolve the human into a vibrant new materiality, then, poses a problem for an adequate account of human domination (and can lead, as Brennan pointed out in Q&A, to a class-obfuscating “green misanthropy”). If we understand our current moment as a historical crisis, Brennan’s provocations suggest that we might turn to the new theoretical possibilities of materialist analysis. If historical materialism barely survived the pressures of a conservative purge, it endures today as a specter haunting the university.

Timothy Brennan, from his faculty page.

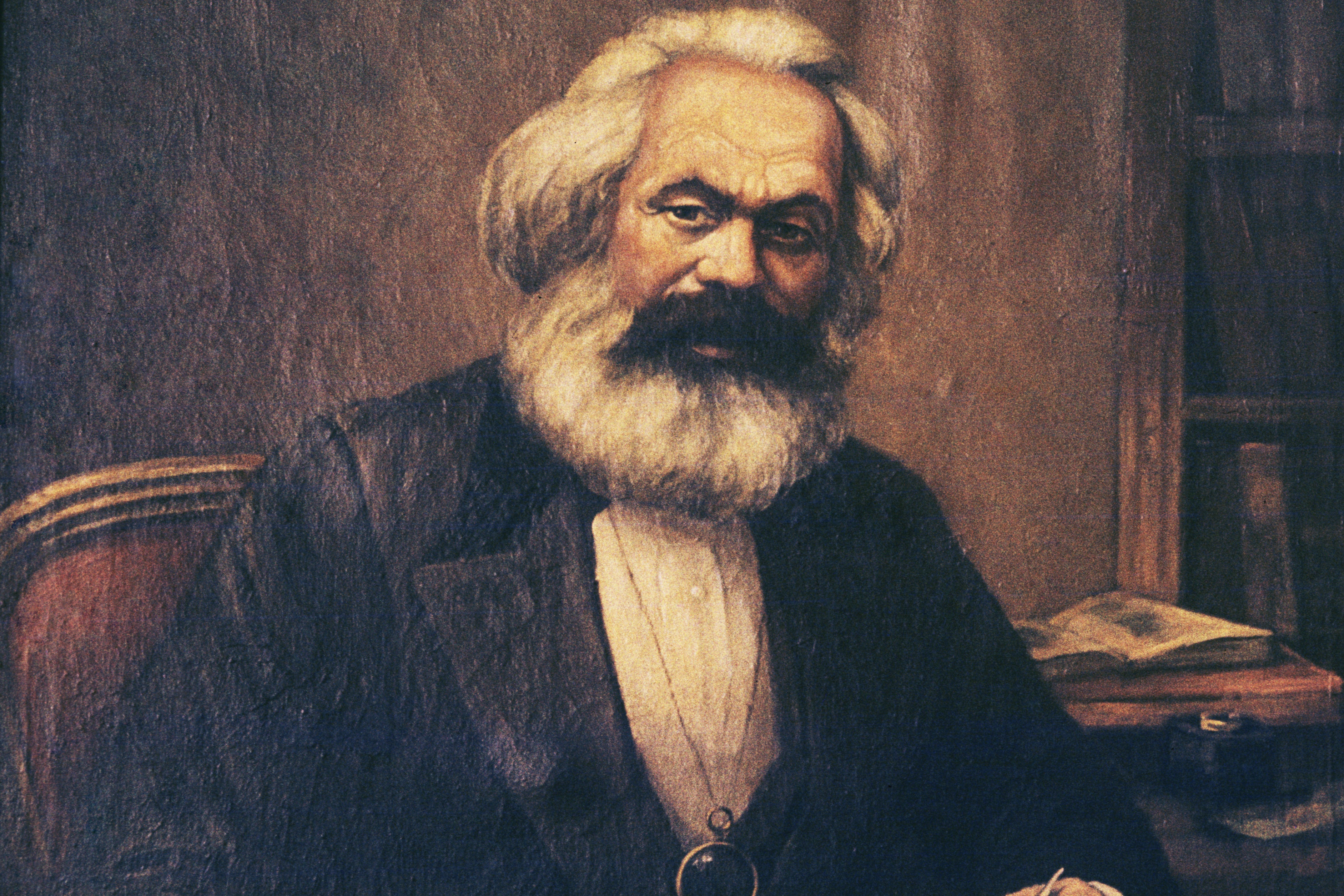

Picture of Marx used in Teen Vogue article.