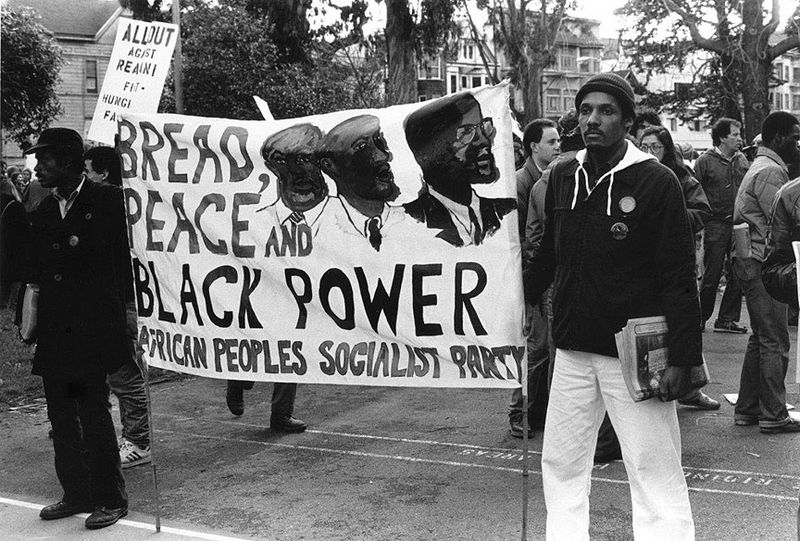

[On March 30, 2019, the Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory hosted a keynote address by Michael Dawson (U of Chicago) entitled "Race, Capitalism & the Current Crisis: Conundrums for Those Who Envisage a Socialist Future," as part of the Racial Capitalism Symposium. Below is a response by Peter Thompson (History).] An Optimistic Socialist Politics for Reparative Justice: Professor Michael Dawson's Keynote Address for the Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory's Racial Capitalism Symposium Written by Peter Thompson Michael Dawson’s keynote address for the Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory’s Racial Capitalism conference examined the theoretical and political implications of his career-long work on black political thought and identity. D. MacArthur Professor of Political Science at the University of Chicago, Dawson has filled a long and productive academic career with publications that probe the importance of a cohesive body of black thought for broader American political debates. Dawson’s talk, entitled “Race, Capitalism, and the Current Crisis: Conundrums for Those Who Envisage a Socialist Future,” began by historically situating both radical black activism and the attempts to study that activism as a singular phenomenon. Dawson claims that various radical black movements throughout the 20th century have advocated for wholesale structural changes to American society with the intention of achieving a socialist future that resonates with many of today’s rejuvenated socialist visions. He admits, however, that many of the radical movements of the 1960s and 70s insisted on a prescriptive and normative politics that often discounted the varieties and complexities of difference. However, Dawson contends that the subsequent rise of particularism did not lead to the historical failures of the Left, as is sometimes claimed. In fact, it is crucial to recognize that different histories of oppression generated different demands and approaches to politics. For Dawson, the ultimate successes of any envisioned socialist regime are predicated on the political system’s ability to adjudicate between the various demands that these distinctive histories generate. [caption id="attachment_1895" align="alignnone" width="800"] Black Nationalism in Oakland, CA from Foundsf: Shaping San Francisco's Digital Archive. [/caption] In order to navigate this political negotiation, Dawson presents us with the “regimes of articulation” approach, which claims that “no social category exists in privileged isolation.” Pulling from Anne McClintock’s work, Dawson argues that each demarcation of social difference (e.g. race, gender, class) is set in relation to other categories of subjectivity. However, the power relationships between these categories can be uneven or contradictory in nature. For this reason, each relationship needs to be articulated within its historically specific regime of power. Dawson provides us with the example of “blackness,” which was articulated differently under Jim Crow, although perhaps no less violently, than it was under American slavery. Drawing explicitly on Marx, Dawson further argues that these various relationships, at least in the American context, have always been mediated by capitalism. Traditionally, the capitalist system has lent overwhelming support to the dominant logic of patriarchy and white supremacy. However, Dawson reminds us that this is not always the case, and there are moments of tension where racism and sexism come into conflict with the unrelenting demands for labor exploitation. It is precisely these moments of crisis that create “pressure points” where progressive politics can make inroads. Dawson sees the growth of the anti-colonial, feminist, and black power movements throughout the middle of the twentieth century as examples of the successful navigation of these “pressure points.” He further believes that the contemporary moment provides us with a new crisis and a new opportunity for progressive gains. Focusing more closely on issues of race, Dawson shifts to his political survey work in order to analyze both static and changing American attitudes towards black reparations. Dawson reveals that the majority of white survey respondents rejected the idea of either reparations or apologies for the historical and ongoing injustices of American slavery. Alongside tepid support from other American racial groups, this overwhelming white rejection has led many on the political Left to deem reparative justice a far too divisive topic for real political discussion. But, in referring back to his “regime of articulation” construction, Dawson insists that a functional reparative justice campaign needs to hold all people responsible for ongoing and past injustice. If taken seriously, this campaign would use all available methods, including but not limited to: truth and reconciliation hearings, educational outreach, changes to national monuments and the historical record, and aid programs for targeted groups. For Dawson, this reparative justice campaign is part of a moral imperative inherent to any truly social-democratic system. [caption id="attachment_1896" align="aligncenter" width="1050"]

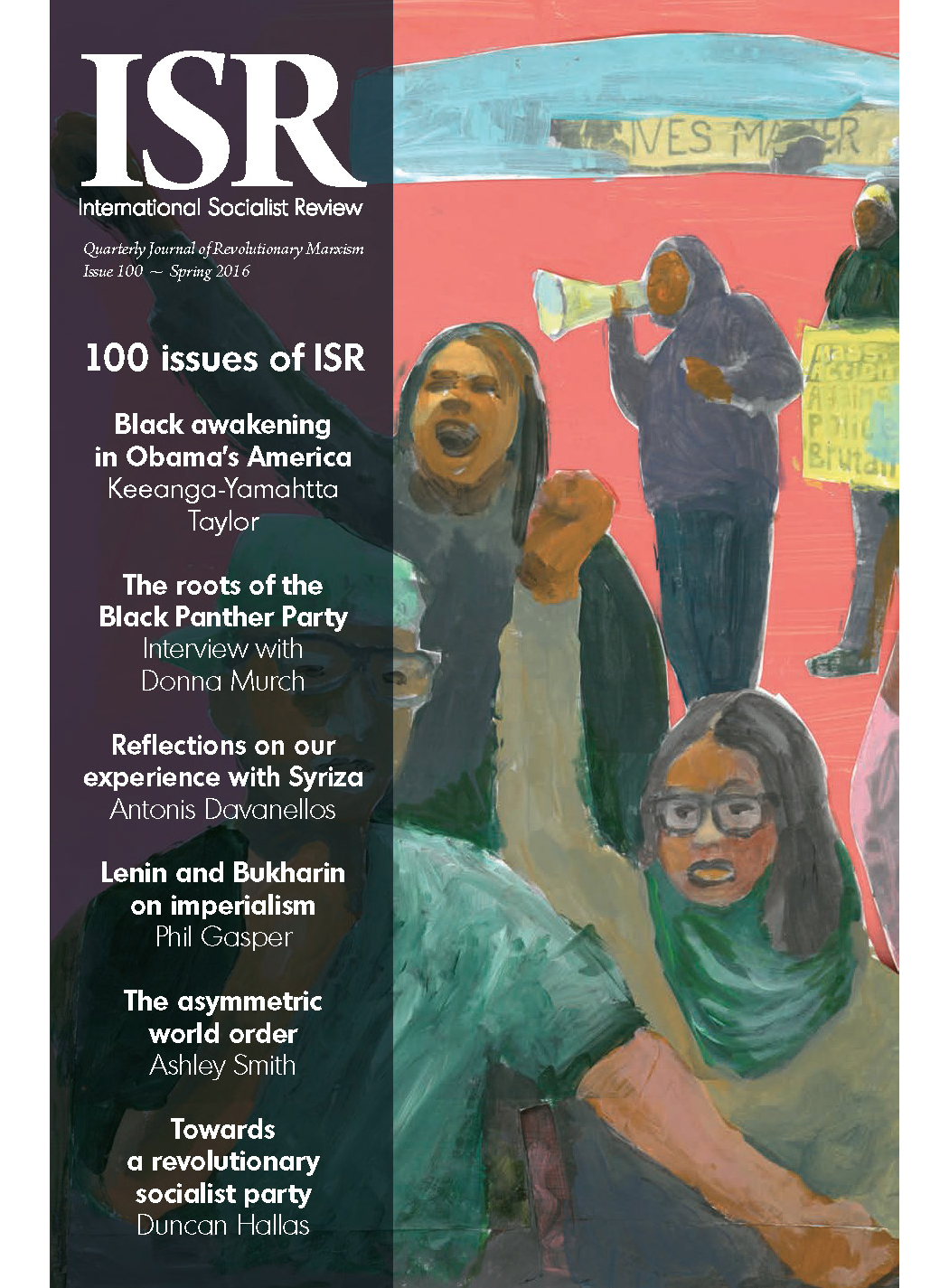

Black Nationalism in Oakland, CA from Foundsf: Shaping San Francisco's Digital Archive. [/caption] In order to navigate this political negotiation, Dawson presents us with the “regimes of articulation” approach, which claims that “no social category exists in privileged isolation.” Pulling from Anne McClintock’s work, Dawson argues that each demarcation of social difference (e.g. race, gender, class) is set in relation to other categories of subjectivity. However, the power relationships between these categories can be uneven or contradictory in nature. For this reason, each relationship needs to be articulated within its historically specific regime of power. Dawson provides us with the example of “blackness,” which was articulated differently under Jim Crow, although perhaps no less violently, than it was under American slavery. Drawing explicitly on Marx, Dawson further argues that these various relationships, at least in the American context, have always been mediated by capitalism. Traditionally, the capitalist system has lent overwhelming support to the dominant logic of patriarchy and white supremacy. However, Dawson reminds us that this is not always the case, and there are moments of tension where racism and sexism come into conflict with the unrelenting demands for labor exploitation. It is precisely these moments of crisis that create “pressure points” where progressive politics can make inroads. Dawson sees the growth of the anti-colonial, feminist, and black power movements throughout the middle of the twentieth century as examples of the successful navigation of these “pressure points.” He further believes that the contemporary moment provides us with a new crisis and a new opportunity for progressive gains. Focusing more closely on issues of race, Dawson shifts to his political survey work in order to analyze both static and changing American attitudes towards black reparations. Dawson reveals that the majority of white survey respondents rejected the idea of either reparations or apologies for the historical and ongoing injustices of American slavery. Alongside tepid support from other American racial groups, this overwhelming white rejection has led many on the political Left to deem reparative justice a far too divisive topic for real political discussion. But, in referring back to his “regime of articulation” construction, Dawson insists that a functional reparative justice campaign needs to hold all people responsible for ongoing and past injustice. If taken seriously, this campaign would use all available methods, including but not limited to: truth and reconciliation hearings, educational outreach, changes to national monuments and the historical record, and aid programs for targeted groups. For Dawson, this reparative justice campaign is part of a moral imperative inherent to any truly social-democratic system. [caption id="attachment_1896" align="aligncenter" width="1050"] Cover from the International Socialist Review with articles on Black Lives Matter and the roots of the Black Panther Party. Content is "copyleft" by the International Socialist Review.[/caption] Dawson concludes by calling for an embrace of what he calls “pragmatic utopianism.” He fully embraces the power of utopian vision, rejecting those who place limits on the realm of possibility. The historical successes of progressive black movements, he argues, are a testament to the ability to push beyond the conceivable. However, pragmatism comes into play when entering into the political arena and strategizing the path towards the ideal. Dawson admits that this process has been troubled of late by the rapidly emerging environmental crisis. While granting that the “expropriation of the earth” has not been a significant focus within his research, he gestures to the work of John Bellamy Foster and Brett Clark to point out that the exploitation of racially-specific labor has significantly contributed to the destruction of the Earth. Audience questions initially revolved around Dawson’s survey work, asking whether similar studies had been done for indigenous peoples and how wording and context impacted survey responses. In response to a question regarding praxis that queried how one balances political demands and moral claims in the process of “pragmatic utopianism,” Dawson stated that while moral demands for justice should always remain central to our overall vision, pragmatic politics should effectively drive our push for specific gains. Subsequent questions returned to the environmental and probed the role of technology in both emancipatory and oppressive political regimes. Discussion then moved to the role of the academy in oppression, interrogating the ability of academics to enact real change. Finally, in a gesture towards the problems of today, Dawson was asked to illuminate the distinct “pressure points” in the contemporary political landscape. He quickly jumped to the fact that real wages are currently falling for most Americans, impelling some to attempt to maintain the illusion of social mobility in order to safeguard racial and gender hierarchies. However, in a moment of optimism, Dawson pointed to the open horizon of the political moment, insisting that the often-competing demands of the various groups within a “regime of articulation” would be hammered out through the intersectional approach of 21st century community politics. This, he rephrased in a subsequent response, is the act of “getting people to see the same world.”

Cover from the International Socialist Review with articles on Black Lives Matter and the roots of the Black Panther Party. Content is "copyleft" by the International Socialist Review.[/caption] Dawson concludes by calling for an embrace of what he calls “pragmatic utopianism.” He fully embraces the power of utopian vision, rejecting those who place limits on the realm of possibility. The historical successes of progressive black movements, he argues, are a testament to the ability to push beyond the conceivable. However, pragmatism comes into play when entering into the political arena and strategizing the path towards the ideal. Dawson admits that this process has been troubled of late by the rapidly emerging environmental crisis. While granting that the “expropriation of the earth” has not been a significant focus within his research, he gestures to the work of John Bellamy Foster and Brett Clark to point out that the exploitation of racially-specific labor has significantly contributed to the destruction of the Earth. Audience questions initially revolved around Dawson’s survey work, asking whether similar studies had been done for indigenous peoples and how wording and context impacted survey responses. In response to a question regarding praxis that queried how one balances political demands and moral claims in the process of “pragmatic utopianism,” Dawson stated that while moral demands for justice should always remain central to our overall vision, pragmatic politics should effectively drive our push for specific gains. Subsequent questions returned to the environmental and probed the role of technology in both emancipatory and oppressive political regimes. Discussion then moved to the role of the academy in oppression, interrogating the ability of academics to enact real change. Finally, in a gesture towards the problems of today, Dawson was asked to illuminate the distinct “pressure points” in the contemporary political landscape. He quickly jumped to the fact that real wages are currently falling for most Americans, impelling some to attempt to maintain the illusion of social mobility in order to safeguard racial and gender hierarchies. However, in a moment of optimism, Dawson pointed to the open horizon of the political moment, insisting that the often-competing demands of the various groups within a “regime of articulation” would be hammered out through the intersectional approach of 21st century community politics. This, he rephrased in a subsequent response, is the act of “getting people to see the same world.”