[On March 5, 2019, the Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory hosted a lecture by Nicholson Distinguished Scholar Ananya Roy (UCLA) entitled “Racial Banishment: A Postcolonial Critique of the Urban Condition in America.” Below is a response by Nubras Samayeen (Landscape Architecture) and Cameron McCarthy (Education).]A Necropolitical Landscape: Life and Death in Great American CitiesWritten by Nubras Samayeen and Cameron McCarthyIntroduction [caption id="attachment_1882" align="aligncenter" width="1430"] Opening slide to Ananya Roy's lecture at UIUC, March 5, 2019[/caption] Ananya Roy delivered an enthralling talk on Tuesday, March 5. In it, she challenged the audience to confront the inadequacies of our lexicon for understanding the racial dimensions of urban transformation today. Roy focused on the question of how we understand cities in present-day America, underscoring their role in the perpetuation of inequality, racial banishment, and the re-segregation of the working class and minority poor. Roy traced a trajectory she has carved out over the years in prior works that include Calcutta Requiem: Gender and the Politics of Poverty (2007), Worlding Cities: Asian Experiments and the Art of Being Global (2011), and Poverty Capital: Microfinance and the Making of Development (2010). This line of thinking is also succinctly elaborated in articles such as “Who’s Afraid of Postcolonial Theory?” (2016). For Roy, it is critically important to see the nexus between locally situated issues of racialized displacement and poverty and their global and transnational connections. She argues that racialization and inequality are not isolated phenomena but global ones. Crucially, she suggests, these processes demonstrate a “colonial relationality.” This colonial relationality is not simply a leftover transaction operating in the Third World, but it is rooted and continuously produced in the American landscape. Roy illustrates this claim with multiple case studies that call attention to the processes of what she calls “racial banishment.” Racial banishment is a way of conceptualizing the constant displacement of populations and the epistemic and material violence that state and municipal authorities orchestrate in city spaces such as Oakland, Los Angeles, the San Francisco Bay Area, and Lakewood (Ohio). For Roy, these matters are existentially rooted in the elaboration of urban spaces across the US. They are not simply “new” developments associated with neoliberalism and gentrification. Rather, the racialization of city space reaches back to slavery. We are living in the “afterlife of slavery,” as black geographers and postcolonial scholars have maintained. Given the limitations of space, it is not possible to address the full range and significance of Roy’s talk. In what follows, I highlight some of her most important arguments and themes. Eviction - Displacement- Gentrification [caption id="attachment_1881" align="alignnone" width="920"]

Opening slide to Ananya Roy's lecture at UIUC, March 5, 2019[/caption] Ananya Roy delivered an enthralling talk on Tuesday, March 5. In it, she challenged the audience to confront the inadequacies of our lexicon for understanding the racial dimensions of urban transformation today. Roy focused on the question of how we understand cities in present-day America, underscoring their role in the perpetuation of inequality, racial banishment, and the re-segregation of the working class and minority poor. Roy traced a trajectory she has carved out over the years in prior works that include Calcutta Requiem: Gender and the Politics of Poverty (2007), Worlding Cities: Asian Experiments and the Art of Being Global (2011), and Poverty Capital: Microfinance and the Making of Development (2010). This line of thinking is also succinctly elaborated in articles such as “Who’s Afraid of Postcolonial Theory?” (2016). For Roy, it is critically important to see the nexus between locally situated issues of racialized displacement and poverty and their global and transnational connections. She argues that racialization and inequality are not isolated phenomena but global ones. Crucially, she suggests, these processes demonstrate a “colonial relationality.” This colonial relationality is not simply a leftover transaction operating in the Third World, but it is rooted and continuously produced in the American landscape. Roy illustrates this claim with multiple case studies that call attention to the processes of what she calls “racial banishment.” Racial banishment is a way of conceptualizing the constant displacement of populations and the epistemic and material violence that state and municipal authorities orchestrate in city spaces such as Oakland, Los Angeles, the San Francisco Bay Area, and Lakewood (Ohio). For Roy, these matters are existentially rooted in the elaboration of urban spaces across the US. They are not simply “new” developments associated with neoliberalism and gentrification. Rather, the racialization of city space reaches back to slavery. We are living in the “afterlife of slavery,” as black geographers and postcolonial scholars have maintained. Given the limitations of space, it is not possible to address the full range and significance of Roy’s talk. In what follows, I highlight some of her most important arguments and themes. Eviction - Displacement- Gentrification [caption id="attachment_1881" align="alignnone" width="920"] Activist imagery protesting Gentrification, from Ananya Roy's lecture[/caption]

Activist imagery protesting Gentrification, from Ananya Roy's lecture[/caption]

“I view banishment not as a corollary to processes of neo-liberalization but rather as integral and foundational in the organization of urban spaces.”

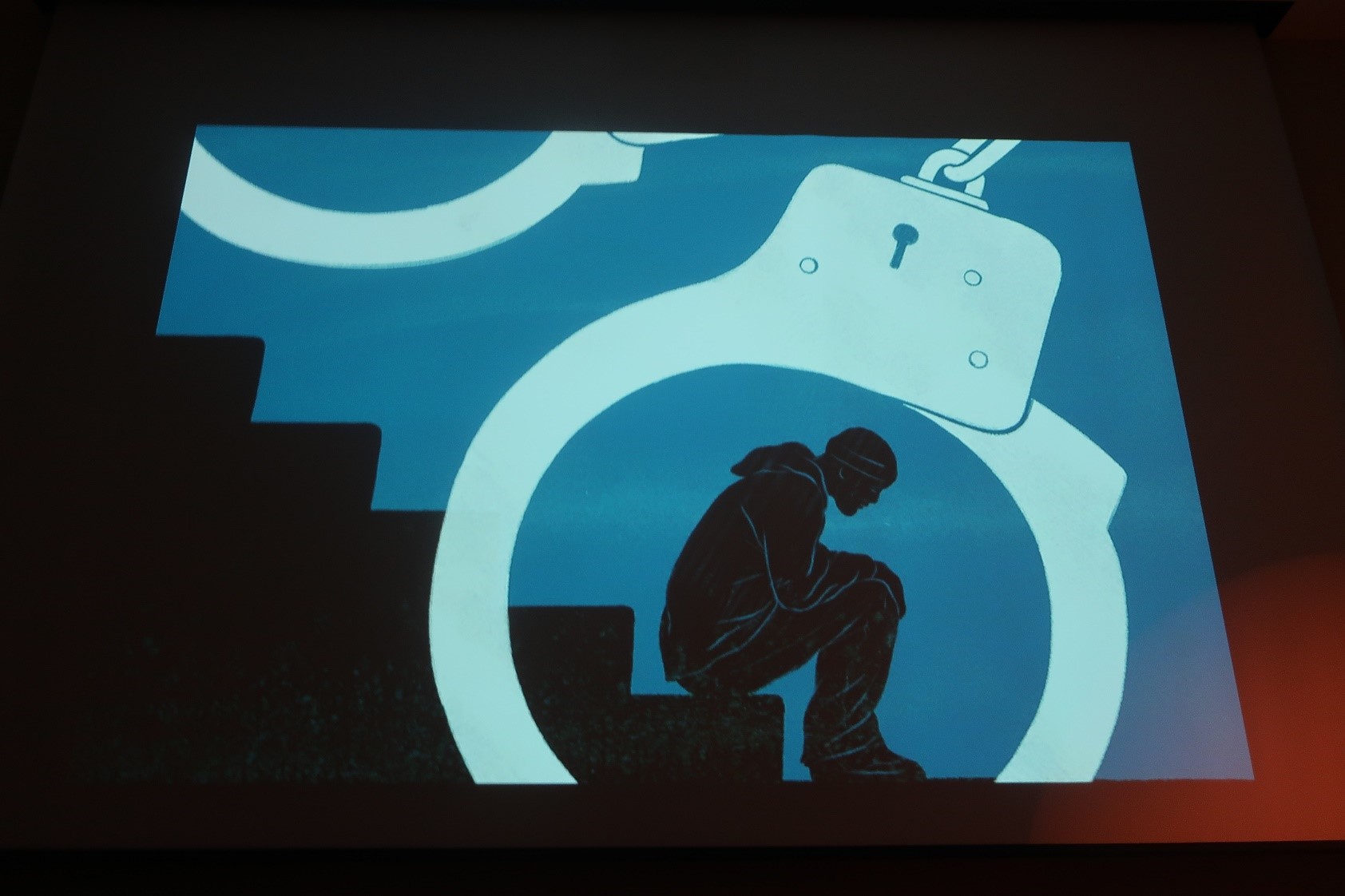

One of the main themes of Roy’s talk was epistemic violence. She maintains that this form of violence expresses itself principally in strategies and policies of racial banishment integral to the construction of the landscape of American metropolises and world cities. She argues that these displacements are not simply centered in the market. Instead, they are systematic practices of state-instituted violence that target black and brown bodies and clinically usurp their right to dwell in the global city. Inherent in policies of banishment and displacement is the raw materiality of colonizing power relationships. [caption id="attachment_1883" align="aligncenter" width="1684"] The Criminalization of Innocence, from Ananya Roy's lecture[/caption] While she analyzed the processes of racial banishment, she also highlighted the social movements contesting exclusion through ongoing struggles over city spaces, property, and public services. This fight is over the very livelihoods and social reproduction of poor and minority urban populations. For instance, a mundane, day-to-day activity like taking children to their schools becomes a crime for impoverished and dislocated families because of recent ordinances criminalizing vehicle dwelling. What life do such marginalized groups have? Roy pointed to the growing number of municipal codes aimed at declaring minority and migrant presence in the city as an existential “nuisance” and, therefore, deserving of elimination. These codes are critical to predatory extraction and accumulation by dispossession as new developers carve their way through highly prized, “historic” black and brown spaces of the city (Bronzeville and Pilsen in Chicago) in pursuit of land for new construction and development.

The Criminalization of Innocence, from Ananya Roy's lecture[/caption] While she analyzed the processes of racial banishment, she also highlighted the social movements contesting exclusion through ongoing struggles over city spaces, property, and public services. This fight is over the very livelihoods and social reproduction of poor and minority urban populations. For instance, a mundane, day-to-day activity like taking children to their schools becomes a crime for impoverished and dislocated families because of recent ordinances criminalizing vehicle dwelling. What life do such marginalized groups have? Roy pointed to the growing number of municipal codes aimed at declaring minority and migrant presence in the city as an existential “nuisance” and, therefore, deserving of elimination. These codes are critical to predatory extraction and accumulation by dispossession as new developers carve their way through highly prized, “historic” black and brown spaces of the city (Bronzeville and Pilsen in Chicago) in pursuit of land for new construction and development.

“Gentrification is urban colonialism.”

Roy insists that this systematic codification and structured criminalization is the linchpin of a new system of Jim Crow re-segregation of city spaces today. It is a new policy offensive that builds on the racialized practices associated with redlining policies of the past and that now creates a re-segregated urban landscape in the United States. Minority dwellings become the “eviction hotpots” in a new paradigm of re-spatialization of the city. Roy echoes Kate Derickson’s critique in her 2010 article, “Unbearable Whiteness of Geography”. For Derickson as well as Roy, the process of systematic dislocation, eviction, and consequent victimization of the urban poor must be placed under the broader umbrella of colonization. These processes are too often euphemized in mainstream social science and urban policy discourses. Terms such as “suburbanization,” “poverty de-concentration,” and “residential mobility” effectively hide the material and epistemic violence of urban transformation. The spatial dynamic of the creation and transformation of the urban core, or the eviction hotspot paradigm, is a relationship of colonizers to the colonized. These developments demand an analysis that integrates the lenses of post-colonial theory and black geography, both of which address the condition and fate of subaltern victims of a deeply racialized capitalism. Roy follows Edward Said in thinking of the subaltern as the Other (Orientalism) and Gayatri Spivak in understanding the subaltern as the one “who does not speak, but is spoken for” (Gayatri Spivak, Can the Subaltern Speak? 2010). Roy also draws on Katherine McKittrick’s work, which connects contemporary racializing practices to the persistence of the coloniality of power. Building on the work of scholars writing in the disciplinary traditions of black geography and postcolonial theory, Roy seeks to deepen the audience’s understanding of the new spatial politics of race in an unfolding transnational order. Race, Space, and Inequality

“Freedom dreams are global in scope.”

[caption id="attachment_1879" align="aligncenter" width="484"] View from West Bank, towards the settlement Ma’ale Adumim[/caption] [caption id="attachment_1878" align="aligncenter" width="510"]

View from West Bank, towards the settlement Ma’ale Adumim[/caption] [caption id="attachment_1878" align="aligncenter" width="510"] Image drawn by children living in the Bedouin Village, who look upon Ma'ale Adumim[/caption] Colonial rationality and racial exploitation, Roy argues, are not solely American issues, but are related to broader practices of political subjection. She highlights the continuum of concern over racial colonization in transcultural urban geography. Following Oren Yiftachel’s concept of “grey spaces,” Roy demonstrates the operationalization of the coloniality of power in her discussion of the Israeli state’s relationship to persecuted Palestinians on the West Bank. A strip of land named Area C in the West Bank (where Israel has full control over civil and security matters, including planning, development, construction, and infrastructure) is a place of competing narratives. There, the opposition between the colonizers and the colonized is palpably on display. In the foreground of the image of the strip is the nondescript territory of the Other. Who dwells there in this dump-like allotment of makeshift huts? Israeli state planning has baptized this displaced leg of the desert with the official term “Bedouin Village.” The people here are subject to arbitrary removals and interdictions, almost constantly. But on the horizon, on the other side of this strip of territory, lies the sprawling Jewish Settlement of Ma’ale Adumim. Upscale in its suburbanization, Ma’ale Adumim is an unlawful settlement according to international law. Yet, despite its illegal status, the Israeli state funds and resources the premium buildings that can be seen from the dump-like spaces of the dwellers of the Bedouin Village. The cruel irony of this opposition is not lost on the young dwellers of the Village. In a self-built, self-run kindergarten, the children of the unrecognized Bedouin look toward the horizon. They see the possibility they are denied. The children, therefore, only draw the homes that they see every day from their harsh existence on the other side of the colonial divide. In this divided frontier, according to Roy, where Palestinians dream of living in homes like those of their colonizers, we see the materialization of the harshest form of segregation: “They (the children of the Bedouin Village school) can never ever even physically enter the settlement homes of Ma’ale Adumim.” Yet their aspirations are coded in their drawings and paintings. Roy connects her analysis of the settlement and the Village to Michel Foucault’s idea of biopolitics and Achille Mbembe’s analytic of necropolitics according to which institutions decide “who may live and who may die.” The gap between where the children live and what they see is agonizing. It seems to be an urgent plea to both local and international policymakers: “Look what the children are drawing about their everyday lives!” How do we respond to where the dreams of these youngsters are leading us? What is the responsibility of Western viewers of such stark processes of deprivation? How does this relate to our known world where eviction, displacement, and expulsion are also part of everyday life? How might we reimagine a different relationship to urban space—to land? Blackness, Poverty, and Aesthetics

Image drawn by children living in the Bedouin Village, who look upon Ma'ale Adumim[/caption] Colonial rationality and racial exploitation, Roy argues, are not solely American issues, but are related to broader practices of political subjection. She highlights the continuum of concern over racial colonization in transcultural urban geography. Following Oren Yiftachel’s concept of “grey spaces,” Roy demonstrates the operationalization of the coloniality of power in her discussion of the Israeli state’s relationship to persecuted Palestinians on the West Bank. A strip of land named Area C in the West Bank (where Israel has full control over civil and security matters, including planning, development, construction, and infrastructure) is a place of competing narratives. There, the opposition between the colonizers and the colonized is palpably on display. In the foreground of the image of the strip is the nondescript territory of the Other. Who dwells there in this dump-like allotment of makeshift huts? Israeli state planning has baptized this displaced leg of the desert with the official term “Bedouin Village.” The people here are subject to arbitrary removals and interdictions, almost constantly. But on the horizon, on the other side of this strip of territory, lies the sprawling Jewish Settlement of Ma’ale Adumim. Upscale in its suburbanization, Ma’ale Adumim is an unlawful settlement according to international law. Yet, despite its illegal status, the Israeli state funds and resources the premium buildings that can be seen from the dump-like spaces of the dwellers of the Bedouin Village. The cruel irony of this opposition is not lost on the young dwellers of the Village. In a self-built, self-run kindergarten, the children of the unrecognized Bedouin look toward the horizon. They see the possibility they are denied. The children, therefore, only draw the homes that they see every day from their harsh existence on the other side of the colonial divide. In this divided frontier, according to Roy, where Palestinians dream of living in homes like those of their colonizers, we see the materialization of the harshest form of segregation: “They (the children of the Bedouin Village school) can never ever even physically enter the settlement homes of Ma’ale Adumim.” Yet their aspirations are coded in their drawings and paintings. Roy connects her analysis of the settlement and the Village to Michel Foucault’s idea of biopolitics and Achille Mbembe’s analytic of necropolitics according to which institutions decide “who may live and who may die.” The gap between where the children live and what they see is agonizing. It seems to be an urgent plea to both local and international policymakers: “Look what the children are drawing about their everyday lives!” How do we respond to where the dreams of these youngsters are leading us? What is the responsibility of Western viewers of such stark processes of deprivation? How does this relate to our known world where eviction, displacement, and expulsion are also part of everyday life? How might we reimagine a different relationship to urban space—to land? Blackness, Poverty, and Aesthetics

“The antonym of ‘racial banishment’ is freedom…. freedom dreams are global in scope”

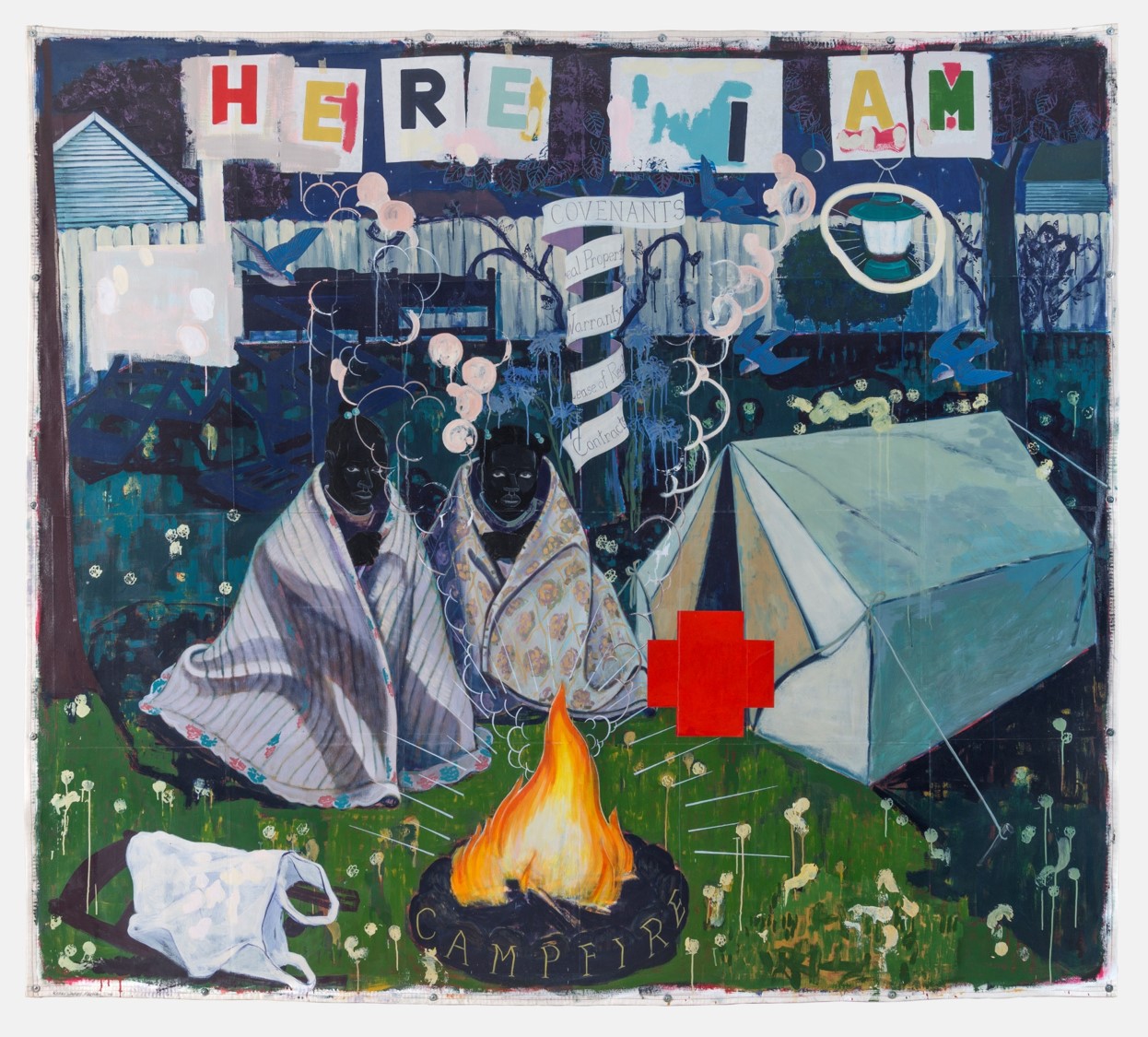

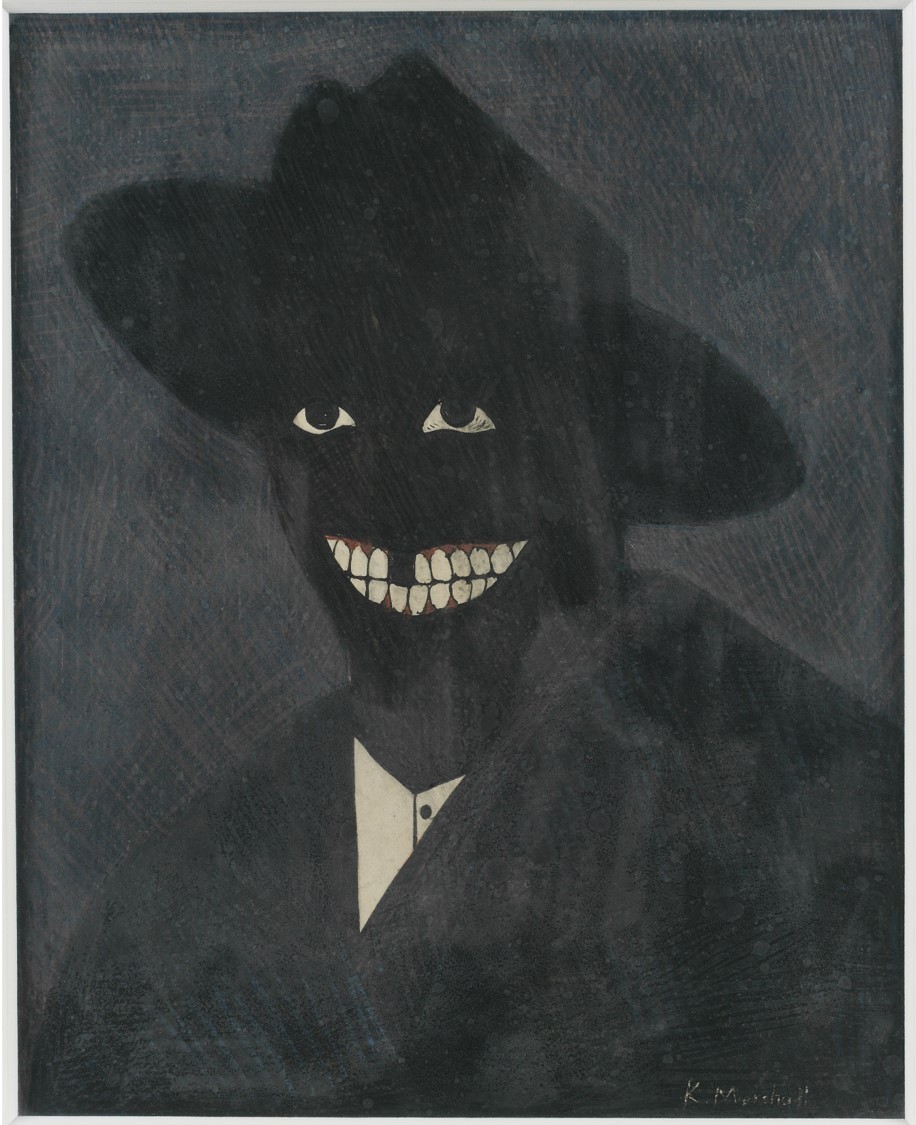

[caption id="attachment_1877" align="aligncenter" width="1246"] Kerry James Marshall, Campfire Girls, 1995. Marshall's paintings elucidate the black landscape.[/caption]

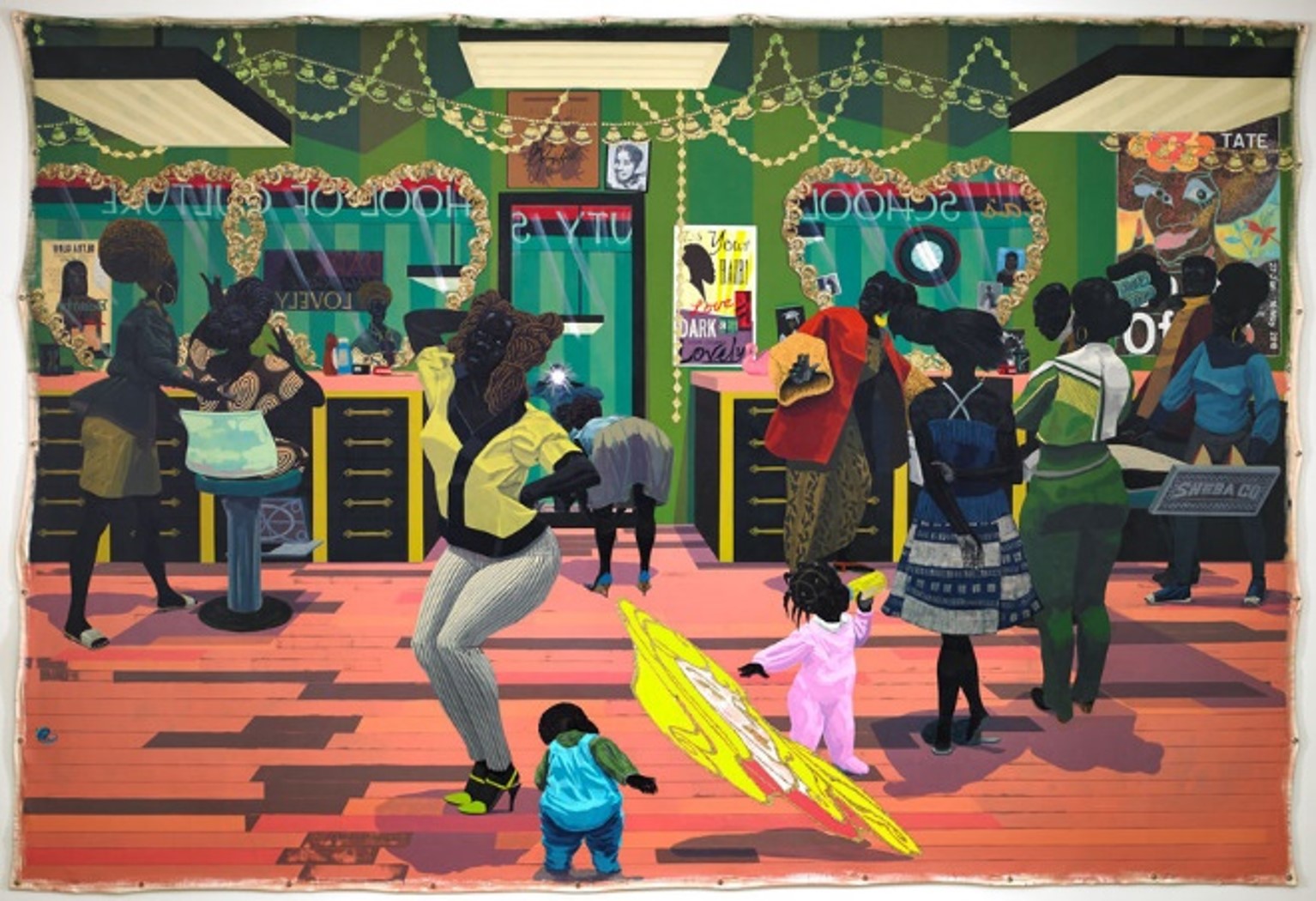

Kerry James Marshall, Campfire Girls, 1995. Marshall's paintings elucidate the black landscape.[/caption]  Kerry James Marshall, A Portrait of the Artist as a shadow of His Former Self, 1980. Roy opens up consideration of answers to these questions in an intellectual space that is customarily treated as opposed to political and policy solutions: the aesthetic. She points to critiques of urban life and visions of transformation offered in black aesthetics as a way to think about alternatives and change. The part of her talk that was particularly fascinating in this area was her discussion of the suggestive politics in the work of the black painter, Kerry James Marshall. As Roy observes, in paintings such as “School of Beauty, School of Culture,” “Camp Fire Girls” and “In Memory Of,” Marshall offers us an interesting place to enter simply because of his reversal of the frame of examination. In contrast to critical and normative scholarship, which sets aesthetics against policy, maintaining that aestheticization compromises the political will, Roy’s carefully chosen examples offer precisely the opposite. They offer an aesthetic vision of the possibility of a world as viewed from the vantage point of the displaced. In Marshall’s work, the excluded members of the city are brought back into the city space. Roy maintains that in Marshall’s work, black bodies re-inhabit spaces of public housing and urban gardens bloom in this space. The paintings depict a post-industrial landscape in which interior spaces blend with an external world covered in magic dust. These examples of Marshall’s work were tantalizing.

Kerry James Marshall, A Portrait of the Artist as a shadow of His Former Self, 1980. Roy opens up consideration of answers to these questions in an intellectual space that is customarily treated as opposed to political and policy solutions: the aesthetic. She points to critiques of urban life and visions of transformation offered in black aesthetics as a way to think about alternatives and change. The part of her talk that was particularly fascinating in this area was her discussion of the suggestive politics in the work of the black painter, Kerry James Marshall. As Roy observes, in paintings such as “School of Beauty, School of Culture,” “Camp Fire Girls” and “In Memory Of,” Marshall offers us an interesting place to enter simply because of his reversal of the frame of examination. In contrast to critical and normative scholarship, which sets aesthetics against policy, maintaining that aestheticization compromises the political will, Roy’s carefully chosen examples offer precisely the opposite. They offer an aesthetic vision of the possibility of a world as viewed from the vantage point of the displaced. In Marshall’s work, the excluded members of the city are brought back into the city space. Roy maintains that in Marshall’s work, black bodies re-inhabit spaces of public housing and urban gardens bloom in this space. The paintings depict a post-industrial landscape in which interior spaces blend with an external world covered in magic dust. These examples of Marshall’s work were tantalizing.

Kerry James Marshall, School of Beauty, School of Culture, 2012

“The US is a post-colony where the post-colony has not arrived.”

Roy brought her fine lecture to a powerful and hopeful conclusion. What Marshall’s paintings allow him to represent is the pent-up desire in colonized urban space to overcome the heavy constraints weighing down the urban poor. In connecting her work on the Global South to that of the present-day American metropolis, Roy points the audience’s attention to the links between localized asymmetries and the globalizing logics governing world cities. Urban spaces are ineluctably spaces of power. We to need re-historicize the racially corroded relationships in the city. We need to re-situate local dynamics in the West within the larger theater of transnational transactions. Finally, she declared, we need to find the political will and the aesthetic imagination to carve new possibilities into the organization of everyday life and the structural arrangements of urban spaces. [caption id="attachment_1874" align="alignnone" width="684"] Final slide from Ananya Roy's lecture[/caption] Note: Among a wide gamut of sources of historians, sociologists, and urbanists, her references particularly emphasized Alex Schafran’s book The Road to Resegregation: Northern California and the Failure of Politics (2018), Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (2012), Douglas Massey’s Categorically Unequal: The American Stratification System (2007), and Matthew Desmond’s Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City (2016).

Final slide from Ananya Roy's lecture[/caption] Note: Among a wide gamut of sources of historians, sociologists, and urbanists, her references particularly emphasized Alex Schafran’s book The Road to Resegregation: Northern California and the Failure of Politics (2018), Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (2012), Douglas Massey’s Categorically Unequal: The American Stratification System (2007), and Matthew Desmond’s Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City (2016).