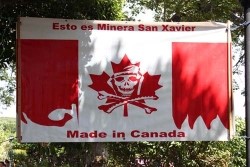

[On March 30, 2019 the Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory hosted the panel "Racial Capitalism and Differential Rights," which was chaired by Jodi Byrd (English/GWS) as part of the Racial Capitalism Symposium. The panel featured the following talks: "Administrating Today's Racial Capitalism Through Differential Rights," by Jodi Melamed (Marquette U) and Chandan Reddy (U Washington) and "'She Was Only Trying to Save Her Life': Disempowered by Self-Defense," by Lisa Cacho (English). Below is a response by Brenda Gisela Garcia (Anthropology).] Response to "Racial Capitalism and Differential Rights" Written by Brenda Gisela Garcia (Anthropology) The panel “Racial Capitalism and Differential Rights” gave the sensation of listening in to a conversation between long-term colleagues Jodi Melamed, Chandan Reddy and Lisa Marie Cacho. Together the panelists examined how deviant, non-heteronormative, and racialized populations became targets of differential rights through capitalist processes of valuation and devaluation. In their paper “Administering Racial Capitalism and Differential Rights” Melamed and Reddy noted that while the notion of rights claims to provide access to political and economic freedom, the administration of rights in a capitalist system prioritizes accumulation over liberation and is shaped by racialized values. For this reason, they propose looking at rights outside their liberal genealogy to understand how racialization and capitalism work together in the present. Drawing on an analogy of glass to think about the concept of administrative power (and thanking Lisa Cacho for the analogy,) Reddy and Melamed explained that administrative powers “encase relations of circulation and violences in transparency. It is what you see through and don’t see and what is obvious and clear but made to appear untouchable. Under the language of liberalism, the administrative powers dematerialize the social and that makes it easy and permissible for a police officer to kill someone...Rule making and morally grounded law allows for the use of repressive force without the discourse of supremacy.” [caption id="attachment_1923" align="align-left" width="250"] "Besides Blackfire's barite mine, the Canadian owned San Xavier mine site in San Luis Potosi has also been the site of conlifct between workers and residents."[/caption] The administration of rights occurs globally, not only in the United States. In parts of the world where resource extraction fuels transnational economies, those perceived ungovernable are managed through bureaucracy, and rights are used to justify extractions. Under the notion of individuality, liberal self-possession, and personal responsibility, collective formations are reconstituted. However, like glass that can shatter, social movements have the potential to shatter administrative regimes “and take aim at the capitalizing capacities.” Reddy and Melamed claim that the neutrality created through humanitarian as well as post-colonial law or civil rights spark scripts of opposition that strengthen relationalities between collectives. The collective becomes a weapon to counter the individualizing processes created by the administration of right as evident in the organizing of queer women of color against the deportation state. By looking at criminalized populations of color, primarily black populations who are dehumanized and rendered disposable, Lisa Cacho seeks to answer the question, “Why don’t we have an ethical crisis?” In her talk titled, “'She was Only Trying to Save Her Life': Disempowered by Self-Defense,” Cacho examined the concept of “complex innocence” through the contradictions of self-defense law. Cacho began by recounting the killing of Darnisha Harris. She was a young black girl shot by a white police officer. She was violating her curfew when police arrived. This caused her to panic, get in her car and try to get away. [caption id="attachment_1924" align="align-right" width="250"]

"Besides Blackfire's barite mine, the Canadian owned San Xavier mine site in San Luis Potosi has also been the site of conlifct between workers and residents."[/caption] The administration of rights occurs globally, not only in the United States. In parts of the world where resource extraction fuels transnational economies, those perceived ungovernable are managed through bureaucracy, and rights are used to justify extractions. Under the notion of individuality, liberal self-possession, and personal responsibility, collective formations are reconstituted. However, like glass that can shatter, social movements have the potential to shatter administrative regimes “and take aim at the capitalizing capacities.” Reddy and Melamed claim that the neutrality created through humanitarian as well as post-colonial law or civil rights spark scripts of opposition that strengthen relationalities between collectives. The collective becomes a weapon to counter the individualizing processes created by the administration of right as evident in the organizing of queer women of color against the deportation state. By looking at criminalized populations of color, primarily black populations who are dehumanized and rendered disposable, Lisa Cacho seeks to answer the question, “Why don’t we have an ethical crisis?” In her talk titled, “'She was Only Trying to Save Her Life': Disempowered by Self-Defense,” Cacho examined the concept of “complex innocence” through the contradictions of self-defense law. Cacho began by recounting the killing of Darnisha Harris. She was a young black girl shot by a white police officer. She was violating her curfew when police arrived. This caused her to panic, get in her car and try to get away. [caption id="attachment_1924" align="align-right" width="250"] Darnisha Harris[/caption] In her panic, she hit a police car and a bystander with her own vehicle. Some witnesses said she had her hands up when Travis Guillot, the police officer, approached her. He was close enough to see that she was an unarmed child. Yet, Guillot shot her using the claim of self-defense. Cacho reminded the audience that this case and many others like it show that children are usually perceived as innocent, except black children. Cacho began to answer her question about why such killings have produced no ethical crisis by using the concept of complex innocence. While policemen across the country who kill people of color often justify their actions through self-defense law, innocent people of color continue to be criminalized and killed. Darnisha, for example, could not be read as fearing for her life or attempting self-preservation. Cacho drew from media and police reports to show that she was probably trying to escape being taken into custody. Meanwhile, Darnisha’s brother did not deny she was violating curfew, but believed that in her encounter with the police, she was just trying to save her life. Cacho examined the colonial history and administrative power of self-defense law. Before the United States existed, self-defense law and the “right to bear arms” allowed the dispossession of indigenous peoples and lands. While black people could defend themselves under self-defense law (against indigenous communities whom black people encountered while escaping white violence), it was only because they were perceived as a source of productive labor. Similarly, enslaved black women could not be victims, but were often criminalized. These colonial hauntings became present in the premature death of Darnisha Harris. When self-defense law allows police to kill a perceived perpetrator, the murder is justified. Cacho highlights that self-defense law grants police an opportunity to narrate their story as noble or heroic, while denying black people the chance to defend themselves. Police take away the complex innocence of people of color even as society views people of color as perpetrators and violent offenders. Speaking of complex innocence, Cacho said “Complex innocence means that people’s responses to being caught are not necessarily proportionate to their wrongdoings. People mess up, lie, and panic even when they do nothing wrong because sometimes they are responding to their family’s social relations or their neighborhood’s racial history more than to their in-the-moment experience. To respect a person’s complex innocence means respecting their humanity, being mindful of their dignity, and suspending judgment until they tell their own stories from their own point of view.” In practice, complex innocence is often afforded only to white, middle-class, heterosexual, cisgendered men, especially state agents and law enforcement. Only the most “privileged can be both victims and agents.”

Darnisha Harris[/caption] In her panic, she hit a police car and a bystander with her own vehicle. Some witnesses said she had her hands up when Travis Guillot, the police officer, approached her. He was close enough to see that she was an unarmed child. Yet, Guillot shot her using the claim of self-defense. Cacho reminded the audience that this case and many others like it show that children are usually perceived as innocent, except black children. Cacho began to answer her question about why such killings have produced no ethical crisis by using the concept of complex innocence. While policemen across the country who kill people of color often justify their actions through self-defense law, innocent people of color continue to be criminalized and killed. Darnisha, for example, could not be read as fearing for her life or attempting self-preservation. Cacho drew from media and police reports to show that she was probably trying to escape being taken into custody. Meanwhile, Darnisha’s brother did not deny she was violating curfew, but believed that in her encounter with the police, she was just trying to save her life. Cacho examined the colonial history and administrative power of self-defense law. Before the United States existed, self-defense law and the “right to bear arms” allowed the dispossession of indigenous peoples and lands. While black people could defend themselves under self-defense law (against indigenous communities whom black people encountered while escaping white violence), it was only because they were perceived as a source of productive labor. Similarly, enslaved black women could not be victims, but were often criminalized. These colonial hauntings became present in the premature death of Darnisha Harris. When self-defense law allows police to kill a perceived perpetrator, the murder is justified. Cacho highlights that self-defense law grants police an opportunity to narrate their story as noble or heroic, while denying black people the chance to defend themselves. Police take away the complex innocence of people of color even as society views people of color as perpetrators and violent offenders. Speaking of complex innocence, Cacho said “Complex innocence means that people’s responses to being caught are not necessarily proportionate to their wrongdoings. People mess up, lie, and panic even when they do nothing wrong because sometimes they are responding to their family’s social relations or their neighborhood’s racial history more than to their in-the-moment experience. To respect a person’s complex innocence means respecting their humanity, being mindful of their dignity, and suspending judgment until they tell their own stories from their own point of view.” In practice, complex innocence is often afforded only to white, middle-class, heterosexual, cisgendered men, especially state agents and law enforcement. Only the most “privileged can be both victims and agents.”