[On March 30, 2019, the Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory hosted a final panel "Racial Capitalism Now: A Conversation with Michael Dawson and Ruth Wilson Gilmore," which was moderated by Jodi Melamed (Marquette U) and Brian Jefferson (Geography. The panel featured a conversation between scholars Michael Dawson (U Chicago) and Ruth Wilson Gilmore (Grad Center, CUNY). Below is a response by Alyssa Bralower (Art History).] Racial Capitalism Then and Now Written by Alyssa Bralower (Art History) The conversation between Michael Dawson and Ruth Wilson Gilmore about contemporary forms of racial capitalism began with the history of Dawson’s and Gilmore’s engagement with issues of race and class in their scholarship and activism. This starting point is inspired by James Baldwin’s observation that “the great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do.”[1] The conversation that unfolded described the social issues and movements that Dawson and Gilmore were involved in early in their lives and a recognition that the field must adapt to the changing flows of capital and racial oppression that would require grappling with finance capitalism, global political economies, and the effects of climate change. Brian Jefferson introduced the event by noting that Dawson and Gilmore are influential figures for a generation of scholars, many of whom had presented at the Racial Capitalism symposium throughout the weekend. Their influence inside and outside the academy emphasizes the importance of activism to theory, and the personal to the social. An undercurrent to the conversation emphasized the importance of generational legacies as a means of both historical preservation and the transmission of knowledge from one generation of scholars to another. Theories of racial capitalism, in the work of scholars like Cedric Robinson, Stuart Hall, and others emerged from Black activist and radical traditions that precede and continue to animate the academic field. Much of the conversation emphasized place, including the significance of cities such as Oakland, Berkeley, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Detroit, as well as the way that activist movements often build alliances across differences of gender, race, and sexuality. The conversation began with the specificity of California as a site for Dawson’s and Gilmore’s initial academic and activist work.[2] Dawson arrived in California as an undergraduate in the Bay Area, led there through an interest in activism that was spurred by the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on April 4, 1968. Dawson underscored the way in which academic research should inform and be informed by one’s activist and political projects. For him, an understanding of the political economy of race in the U.S. was essential for his work as an organizer. For Dawson, a driving question has been why and how the Black Liberation Movement declined in the mid-1970s, when it fell apart “spectacularly and violently” in the Bay Area. While some of the problems that lead to the dissolving of these groups was “self-inflicted,” due to internal contradictions such as violence against women and homophobia within the Black Panther Party, the state played a central role in disbanding Black insurgency nationally and globally. One such state-led effort was the use of gentrification as a “defensive action,” through which the populations in long-standing Black and Japanese American neighborhoods were displaced. While studies of international political economy and its connection to racial oppression, labor, and industrialization/technological development existed, Dawson notes that there was a lack of information about such relations in the U.S as it pertained to race. Dawson’s own subsequent experience working as an organizer in Silicon Valley informed his work in the field. Silicon Valley, which emerged as a tech-hub in the late 1960s as major corporations in the area backed the Vietnam War, is a microcosm of the relations between imperialism, racial oppression, and capitalism. Previous generations of scholars, such as Ralph Bunche, had studied Black politics, primarily at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). However, Dawson notes that the “field of racial politics had been defined previously as the racial attitudes of white citizens in the United States,” and the work that Dawson and his colleagues did was to redefine racial politics as the “the politics and movements of people of color.” [caption id="attachment_1931" align="aligncenter" width="1058"] Protestors blockade private shuttle carrying tech industry employees from their homes in San Francisco to their jobs at the company's campus in Silicon Valley. Katy Steinmetz / TIME. Source.[/caption] Gilmore began by noting that she did not initially set out to write about prisons, as she does in her book Golden Gulag. [A New York Times Magazine profile, which appeared a few days after her talk at the conference, offers a detailed account of her political and philosophical evolution]. Gilmore recounted that living in Los Angeles, where she recognized the conditions of a changing landscape and economy, made her eventually want to study political economy. One of the remarkable things about L.A., Gilmore noted, is that the “contradictions are right on the surface.” Gilmore also discussed the legacy of the Black Panther Party, observing that the organization wasn’t necessarily dangerous because they condoned violence but because of their larger platform and successful programs. Indeed, Los Angeles chapter leaders John Huggins and Bunchy Carter were assassinated as students on the UCLA campus while they were headed to discuss campus curricula. For Gilmore, Huggins’ and Carter’s efforts to debate the future of campus curricula as students represents the type of action that strengthens Black Studies and work in the field of racial capitalism. Gilmore also credits Clyde Wood as a key figure in her thinking, whose influential 1998 study Development Arrested: the Blues and Plantation Power in the Mississippi Delta argues for a study of political economy that accounts for cultural production, what Wood calls the “blues epistemology.” [caption id="attachment_1932" align="alignnone" width="1200"]

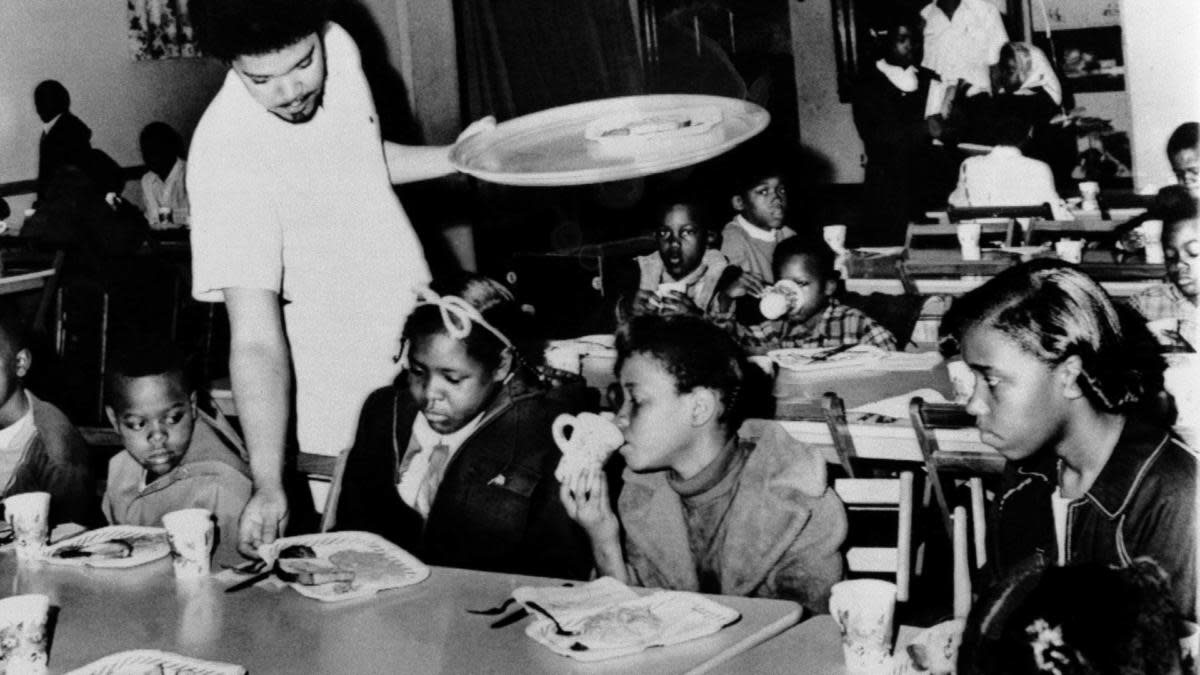

Protestors blockade private shuttle carrying tech industry employees from their homes in San Francisco to their jobs at the company's campus in Silicon Valley. Katy Steinmetz / TIME. Source.[/caption] Gilmore began by noting that she did not initially set out to write about prisons, as she does in her book Golden Gulag. [A New York Times Magazine profile, which appeared a few days after her talk at the conference, offers a detailed account of her political and philosophical evolution]. Gilmore recounted that living in Los Angeles, where she recognized the conditions of a changing landscape and economy, made her eventually want to study political economy. One of the remarkable things about L.A., Gilmore noted, is that the “contradictions are right on the surface.” Gilmore also discussed the legacy of the Black Panther Party, observing that the organization wasn’t necessarily dangerous because they condoned violence but because of their larger platform and successful programs. Indeed, Los Angeles chapter leaders John Huggins and Bunchy Carter were assassinated as students on the UCLA campus while they were headed to discuss campus curricula. For Gilmore, Huggins’ and Carter’s efforts to debate the future of campus curricula as students represents the type of action that strengthens Black Studies and work in the field of racial capitalism. Gilmore also credits Clyde Wood as a key figure in her thinking, whose influential 1998 study Development Arrested: the Blues and Plantation Power in the Mississippi Delta argues for a study of political economy that accounts for cultural production, what Wood calls the “blues epistemology.” [caption id="attachment_1932" align="alignnone" width="1200"] Bill Whitfield, member of the Black Panther chapter in Kansas City, serving free breakfast to children before they go to school. (Credit: William P. Straeter/AP Photo). Source.[/caption] In their acknowledgment of deep legacies within the Black radical tradition, as well as crucial work by Indigenous, Latinx, and Asian American activist groups, both Gilmore and Dawson emphasized that our current political, economic, and social landscape is quite different from the earlier era. A discussion of these legacies led to a discussion of contemporary issues of racial oppression, social justice, and economic inequality. Melamed asked how work on racial capitalism could be used to create reform and unify leftist movements. Dawson’s vision draws on earlier legacies of social reform such as Harry Haywood’s efforts in the early communist movements. A key element of leftist reform is for leftist groups to recognize that the movements for the liberation of people of color and black radical communities are central to revolution, not a distraction from the movement. Dawson also called for a better understanding of financial capitalism, and more nuanced analyses of the capitalism that governs the world. Gilmore added that enlivening the concept of racial capitalism today requires projects that study political economies outside of the U.S. and Europe as a means of creating a more accurate reflection of global capitalism. Invoking Cedric Robinson, Gilmore maintained that capitalism and racial oppression co-developed, one is not necessarily a function of the other. To grapple with this requires studies that “combine specificity with the general trend of capitalism in the world today.” Gilmore cited examples such C.K. Lee’s work on women factory workers in China and Hong Kong and Vijay Prashad’s work on the Global South. Such studies as these have demonstrated that not all capital relations emanate from the global north, but all capital relations are racial. Furthermore, Gilmore also outlined that scholarship on racial capitalism needs to address both the vulnerabilities of the surface of the Earth and its inhabitants through work on climate change and land grabs. The effects of climate change, which vulnerable populations already experience, will create new forms of racial oppression. [caption id="attachment_1933" align="alignnone" width="800"]

Bill Whitfield, member of the Black Panther chapter in Kansas City, serving free breakfast to children before they go to school. (Credit: William P. Straeter/AP Photo). Source.[/caption] In their acknowledgment of deep legacies within the Black radical tradition, as well as crucial work by Indigenous, Latinx, and Asian American activist groups, both Gilmore and Dawson emphasized that our current political, economic, and social landscape is quite different from the earlier era. A discussion of these legacies led to a discussion of contemporary issues of racial oppression, social justice, and economic inequality. Melamed asked how work on racial capitalism could be used to create reform and unify leftist movements. Dawson’s vision draws on earlier legacies of social reform such as Harry Haywood’s efforts in the early communist movements. A key element of leftist reform is for leftist groups to recognize that the movements for the liberation of people of color and black radical communities are central to revolution, not a distraction from the movement. Dawson also called for a better understanding of financial capitalism, and more nuanced analyses of the capitalism that governs the world. Gilmore added that enlivening the concept of racial capitalism today requires projects that study political economies outside of the U.S. and Europe as a means of creating a more accurate reflection of global capitalism. Invoking Cedric Robinson, Gilmore maintained that capitalism and racial oppression co-developed, one is not necessarily a function of the other. To grapple with this requires studies that “combine specificity with the general trend of capitalism in the world today.” Gilmore cited examples such C.K. Lee’s work on women factory workers in China and Hong Kong and Vijay Prashad’s work on the Global South. Such studies as these have demonstrated that not all capital relations emanate from the global north, but all capital relations are racial. Furthermore, Gilmore also outlined that scholarship on racial capitalism needs to address both the vulnerabilities of the surface of the Earth and its inhabitants through work on climate change and land grabs. The effects of climate change, which vulnerable populations already experience, will create new forms of racial oppression. [caption id="attachment_1933" align="alignnone" width="800"] The magnitude of the 2018 wildfires in California are evidence of climate change, which affects vulnerable populations, such as those on the coasts first. Gilmore notes that natural disasters aren't natural at all, but the result of systems built upon racial capitalism. [/caption] Gilmore and Dawson noted that academic scholarship and activist movements operate on different temporalities, so it is important for students to pursue projects that produce knowledge for the social movements in which they are invested. Gilmore concluded by suggesting that the main project for racial capitalism now is to dismantle capitalism. For Gilmore, the undoing of capitalism is not merely a shift in the economic system, but a means of “transforming the world into a new series of economic, political, cultural, and other relations.” [1] James Baldwin, “Unnameable Objects, Unspeakable Crimes,” 1966. [2] Throughout the symposium, California and its many contradictions served as a site where discussions of both legacies and current developments in Racial Capitalism were grounded. Ofelia Ortiz Cueavas (UC Davis), presented on “California Racial Capitalism,” while Cheryl I. Harris (UCLA) discussed California’s 1850 “Act for Governance and Protection of Indians,” as an example of early laws that sought to present as “race-neutral,” but were mobilized against Indigenous populations and populations of color disproportionately. During the conversation between Dawson and Gilmore, Jodi Melamed noted that both Dawson and Gilmore share California as a “formative site of [their] thinking and activism.”

The magnitude of the 2018 wildfires in California are evidence of climate change, which affects vulnerable populations, such as those on the coasts first. Gilmore notes that natural disasters aren't natural at all, but the result of systems built upon racial capitalism. [/caption] Gilmore and Dawson noted that academic scholarship and activist movements operate on different temporalities, so it is important for students to pursue projects that produce knowledge for the social movements in which they are invested. Gilmore concluded by suggesting that the main project for racial capitalism now is to dismantle capitalism. For Gilmore, the undoing of capitalism is not merely a shift in the economic system, but a means of “transforming the world into a new series of economic, political, cultural, and other relations.” [1] James Baldwin, “Unnameable Objects, Unspeakable Crimes,” 1966. [2] Throughout the symposium, California and its many contradictions served as a site where discussions of both legacies and current developments in Racial Capitalism were grounded. Ofelia Ortiz Cueavas (UC Davis), presented on “California Racial Capitalism,” while Cheryl I. Harris (UCLA) discussed California’s 1850 “Act for Governance and Protection of Indians,” as an example of early laws that sought to present as “race-neutral,” but were mobilized against Indigenous populations and populations of color disproportionately. During the conversation between Dawson and Gilmore, Jodi Melamed noted that both Dawson and Gilmore share California as a “formative site of [their] thinking and activism.”