[On March 30, 2019, the Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory hosted the panel “Racial Legacies of Debt, Development and Investment,” which was chaired by Susan Koshy (Director, Unit for Criticism) as part of the Racial Capitalism symposium. The panel featured the following talks: “Debt, Development and Dispossession: Afterlives of Slavery,” by Cheryl Harris (UCLA) and “‘In Search of the Next 'El Dorado': Mining for Capital in a Frontier Market with Colonial Legacies,” by Kimberly Kay Hoang (U Chicago). Below is a response by Lila Ann M. Dodge (Anthropology).] Between a New Global Order and the Enduring Matrix of Dispossession Written by Lila Ann M. Dodge (Anthropology) On March 29th and 30th, the Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory brought together several generations of thinkers and activists working on sites where the racial underpinnings of contemporary capitalism are being rearticulated or exposed in new ways. The symposium’s title, Racial Capitalism, refers to the foundational theorization of “racial capitalism” by the late political and cultural theorist Cedric Robinson: in his 1983 work Black Marxism, Robinson argued that capitalism developed within European societies that were already deeply racialist. The Black radical thinkers whose work Robinson analyzes in part three of the book—W. E. B. DuBois, C. L. R. James, and Richard Wright—eventually found Marxism inadequate for their purposes because it did not own up to its own racialist underpinnings. Chaired by Susan Koshy, the panel, “Racial Legacies of Debt, Development, and Investment,” brought Cheryl Harris and Kimberly Kay Hoang into conversation around financial, legal, and geographic dimensions of contemporary practices of wealth accumulation and its correlate racial dispossession.

- Second edition book cover of Robinson’s Black Marxism, published by the University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

Dr. Harris, Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Professor of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties at the UCLA School of Law, presented a paper titled “Debt, Development, and Dispossession: Afterlives of Slavery.” She began by recognizing the traditional native land on which the event took place, and with an “incantation,” a quote from James Baldwin stressing the persistence of history in the present. Harris examined debt as a mechanism that, precisely by means of the law, serves ongoing capital accumulation through the dispossession and expropriation of the labor—and assets—of people and communities of color in the United States. Building on her earlier work on the fusion of whiteness and property in the U.S. legal system, Harris asked how “the throw-away” is given value, and led the audience through a series of historical, legal, and critical moments that reveal how the “afterlife of slavery” inhabits a “race-neutral” system, reproducing racial dispossession that generates profit for the state and other privileged parties. Spurred by the work of artist Cameron Rowland, Harris began by underlining the productivity of incarceration. The 13th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1865, made slavery illegal in the U.S. except “as punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted…within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” Harris argues that the 13th Amendment thereby transferred the right to use unfree labor from private individuals to the state. Today, the products of prisoners’ labor that Rowland exhibits are sold through nonprofits to government agencies: Harris suggests that, under austerity conditions, these products represent “savings” to the state that are worth more than the profit they might make on the public market. [caption id="attachment_1917" align="aligncenter" width="440"] Cameron Rowland’s Leveler (Extension) Rings for Manhole Openings, 2016. Cast aluminum, pallet, distributed by Corcraft, 118 x 127 x 11 inches. Rental at cost. As pictured in Terence Trouillot’s article “Cameron Rowland 91020000” for The Brooklyn Rail, March 4th, 2016.[/caption] The policing practices that the people of Ferguson, Missouri, brought to public attention following the killing of Michael Brown in 2014 made Harris’ second focal moment. Far in advance of Brown’s murder, the city of Ferguson was issuing arbitrary municipal citations which were overwhelmingly levied on African Americans: the resulting fines generated income for the city, or if unpaid, arrests and time behind bars. The Department of Justice report on the Ferguson Police Department published in 2015 states on page two that “Ferguson’s law enforcement practices are shaped by the City’s focus on revenue rather than by public safety needs.” It likewise confirms racial bias in the police department and court, citing “emails circulated by police supervisors and court staff that stereotype racial minorities as criminals” (page 5). Harris turned to the 19th century to show how these practices issue from a long history of operating debt and development as a “race neutral means of implementing racial dispossession.” Though the United States expanded territorially from East to West, Harris argued that innovations in racial dispossession also moved West to East. California entered the Union as a “free state” in 1850, yet racial subordination underwrote its development. In California’s “narrative of development,” Harris noted, “the project of racial conquest was justified as bestowing benefit on populations in need of improvement.” Harris highlighted California’s 1850 “Act for Governance and Protection of Indians,” which includes some of the first known laws prohibiting and penalizing vagrancy. Under this law, any Indian considered by a white person to be loitering or vagrant could be arrested and penalized with forced labor, which was moreover leased out to individuals. Comparing these to the Black Codes and subsequent laws passed in Southern states after the Civil War, Harris showed how the California vagrancy laws provided a model for post-Emancipation laws that ostensibly lie on race-neutral ground but effectively criminalize unemployment and homelessness, and innovated forms of debt-peonage, convict-leasing and chain-gang labor that produced value through the enforcement of these laws. Harris concluded by unpacking two current cases where “debt crises” are enabling collective dispossession. In Flint, Michigan, the majority African-American city’s debt prompted the state governor to appoint an emergency manager who switched Flint’s water supply in order to save money, but this debt was produced partly by the state’s reduction of revenue to the city. With the ensuing water crisis, Harris contends that debt was offered in solution as well, by increasing Flint’s borrowing power to participate in creating a regional water authority. In Los Angeles, California, Harris traces new predatory lending in the name of “improvement” that disproportionally put people of color into subprime loan status. LA County’s PACE program offers energy efficient home improvements for low and medium income households, paid for by a lien taken against the house. The subcontractors for the program sold “improvements” to homeowners with large price-tags and limited proof of efficacy that have left people with large debts that they cannot afford, that lead swiftly to foreclosures, and that are concentrated in neighborhoods where people of color live. Harris notes that the narrative of improvement continues to serve racial dispossession through permanent emergencies that allow for increased surveillance of cities and neighborhoods and the extraction of “savings.” In Harris’ analysis, the “hollowing out” of value of black geographies and assets actually increases their value, in terms of potential return on debt and investment. [caption id="attachment_1916" align="aligncenter" width="1317"]

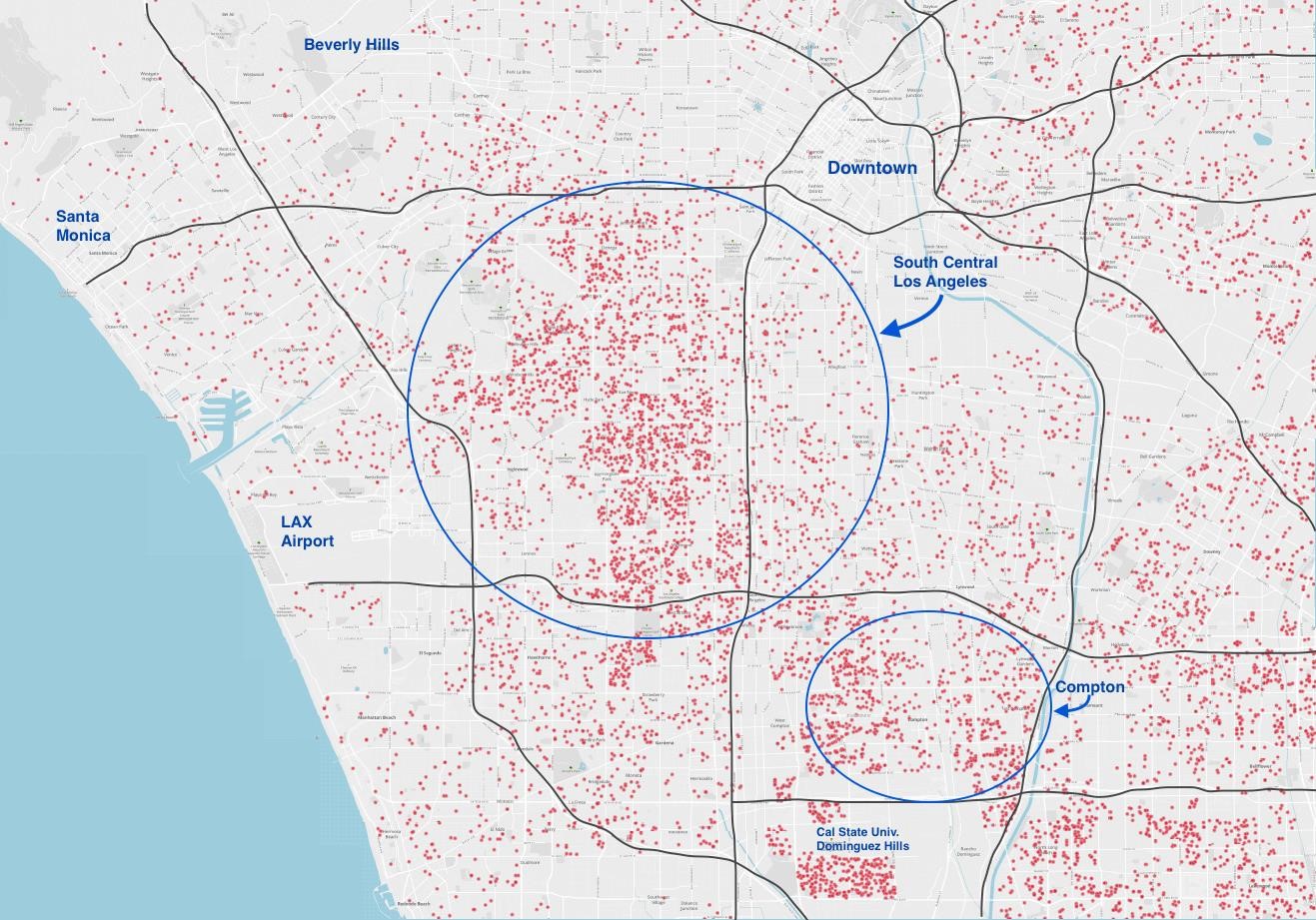

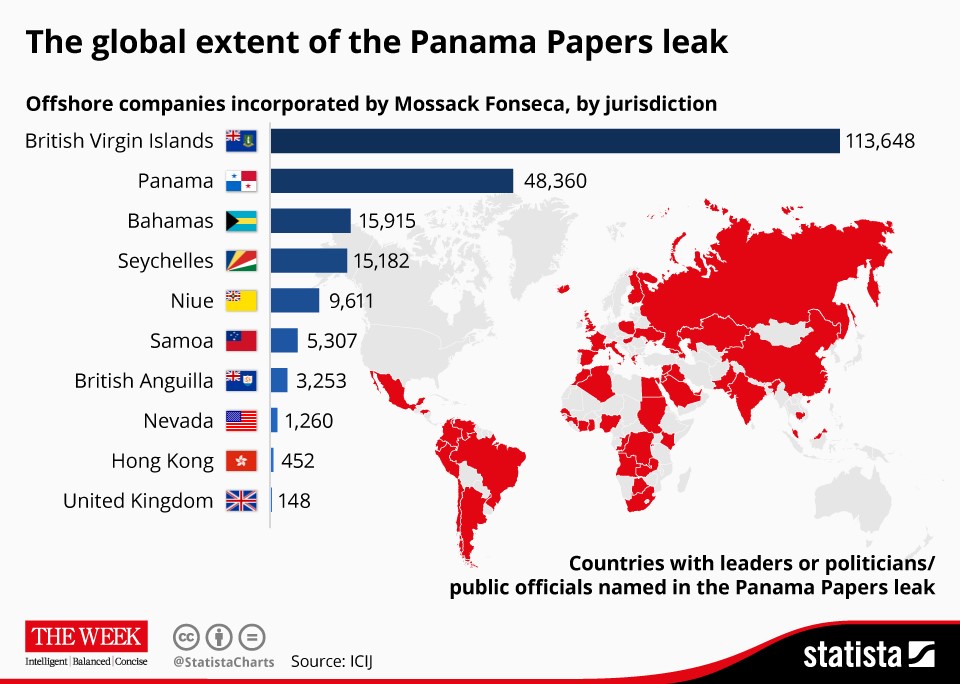

Cameron Rowland’s Leveler (Extension) Rings for Manhole Openings, 2016. Cast aluminum, pallet, distributed by Corcraft, 118 x 127 x 11 inches. Rental at cost. As pictured in Terence Trouillot’s article “Cameron Rowland 91020000” for The Brooklyn Rail, March 4th, 2016.[/caption] The policing practices that the people of Ferguson, Missouri, brought to public attention following the killing of Michael Brown in 2014 made Harris’ second focal moment. Far in advance of Brown’s murder, the city of Ferguson was issuing arbitrary municipal citations which were overwhelmingly levied on African Americans: the resulting fines generated income for the city, or if unpaid, arrests and time behind bars. The Department of Justice report on the Ferguson Police Department published in 2015 states on page two that “Ferguson’s law enforcement practices are shaped by the City’s focus on revenue rather than by public safety needs.” It likewise confirms racial bias in the police department and court, citing “emails circulated by police supervisors and court staff that stereotype racial minorities as criminals” (page 5). Harris turned to the 19th century to show how these practices issue from a long history of operating debt and development as a “race neutral means of implementing racial dispossession.” Though the United States expanded territorially from East to West, Harris argued that innovations in racial dispossession also moved West to East. California entered the Union as a “free state” in 1850, yet racial subordination underwrote its development. In California’s “narrative of development,” Harris noted, “the project of racial conquest was justified as bestowing benefit on populations in need of improvement.” Harris highlighted California’s 1850 “Act for Governance and Protection of Indians,” which includes some of the first known laws prohibiting and penalizing vagrancy. Under this law, any Indian considered by a white person to be loitering or vagrant could be arrested and penalized with forced labor, which was moreover leased out to individuals. Comparing these to the Black Codes and subsequent laws passed in Southern states after the Civil War, Harris showed how the California vagrancy laws provided a model for post-Emancipation laws that ostensibly lie on race-neutral ground but effectively criminalize unemployment and homelessness, and innovated forms of debt-peonage, convict-leasing and chain-gang labor that produced value through the enforcement of these laws. Harris concluded by unpacking two current cases where “debt crises” are enabling collective dispossession. In Flint, Michigan, the majority African-American city’s debt prompted the state governor to appoint an emergency manager who switched Flint’s water supply in order to save money, but this debt was produced partly by the state’s reduction of revenue to the city. With the ensuing water crisis, Harris contends that debt was offered in solution as well, by increasing Flint’s borrowing power to participate in creating a regional water authority. In Los Angeles, California, Harris traces new predatory lending in the name of “improvement” that disproportionally put people of color into subprime loan status. LA County’s PACE program offers energy efficient home improvements for low and medium income households, paid for by a lien taken against the house. The subcontractors for the program sold “improvements” to homeowners with large price-tags and limited proof of efficacy that have left people with large debts that they cannot afford, that lead swiftly to foreclosures, and that are concentrated in neighborhoods where people of color live. Harris notes that the narrative of improvement continues to serve racial dispossession through permanent emergencies that allow for increased surveillance of cities and neighborhoods and the extraction of “savings.” In Harris’ analysis, the “hollowing out” of value of black geographies and assets actually increases their value, in terms of potential return on debt and investment. [caption id="attachment_1916" align="aligncenter" width="1317"] Map of neighborhoods affected by PACE loan debt, as shown in Dr. Harris’ presentation. Produced by Public Counsel, “Nemore v. Renovate America and Ocana v. Renew Financial: Frequently Asked Questions.”[/caption] Dr. Hoang, Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Chicago, presented an excerpt from her current book project, Playing in the Gray, in a paper titled “In Search of the Next ‘El Dorado’: Mining for Capital in a Frontier Market with Colonial Legacies.” In it she studies those at the opposite end of the processes Harris described: the people “who operate with great impunity” in achieving profit, under the aegis of the law. She began by referencing the Panama Papers leak and 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB), two scandals that rocked global finance in 2015, exposing the involvement of political figures and offshore entities in massive accumulation of wealth. Yet Hoang focuses on the smaller transactions, between less prominent people in smaller developing countries, fueling the new global order: the rise of East and Southeast Asia and the declining dominance of the U.S. and Europe now divides the world between “ultra-high net-worth individuals and poor people in both contexts.” Hoang is researching the social relationships that enable investments: sketching a global network of individuals, her qualitative work counters the impossibility of statistically tracing the national origin of capital flows given that investments pass through complex national circuits, tagged only in the final country before investment. [caption id="attachment_1918" align="aligncenter" width="960"]

Map of neighborhoods affected by PACE loan debt, as shown in Dr. Harris’ presentation. Produced by Public Counsel, “Nemore v. Renovate America and Ocana v. Renew Financial: Frequently Asked Questions.”[/caption] Dr. Hoang, Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Chicago, presented an excerpt from her current book project, Playing in the Gray, in a paper titled “In Search of the Next ‘El Dorado’: Mining for Capital in a Frontier Market with Colonial Legacies.” In it she studies those at the opposite end of the processes Harris described: the people “who operate with great impunity” in achieving profit, under the aegis of the law. She began by referencing the Panama Papers leak and 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB), two scandals that rocked global finance in 2015, exposing the involvement of political figures and offshore entities in massive accumulation of wealth. Yet Hoang focuses on the smaller transactions, between less prominent people in smaller developing countries, fueling the new global order: the rise of East and Southeast Asia and the declining dominance of the U.S. and Europe now divides the world between “ultra-high net-worth individuals and poor people in both contexts.” Hoang is researching the social relationships that enable investments: sketching a global network of individuals, her qualitative work counters the impossibility of statistically tracing the national origin of capital flows given that investments pass through complex national circuits, tagged only in the final country before investment. [caption id="attachment_1918" align="aligncenter" width="960"] Map produced by Statista.[/caption] Hoang presented some of her data on investment in Vietnam, analyzing capital flows in and out of the country through a postcolonial lens. Vietnam’s economy is increasingly dominated by inter-Asian capital, which new competition between the U.S. and China and the regulatory outcomes of the 2008 financial crisis facilitate by allowing Vietnamese businesspeople and politicians to turn down Western money in favor of Asian investment. Nevertheless, U.S. investors still have a role to play in Vietnam’s speculative market: linking her presentation to Harris’, Hoang noted how “narratives of development bestow this precious boon” of profit, as illustrated by her interview excerpts with an American running speculative mining operations in Vietnam. In a context of “heterogeneous state-market relations,” access to Vietnamese markets requires connections with the Communist party. For foreign investors, Hoang contends, “the speculation is socialized through personal ties that shape markets and mitigate risk” especially by giving investors an apparently insider view of the market. However, behind the opacity of legal structures and information, foreign investors take the initial risk of expending large amounts of capital in “frontier” markets to discover a new “El Dorado,” but Vietnamese government officials are able to push them out once a market has been developed. Hoang describes this as a reconstitution of historical dynamics of globalization, as patterned by colonization, neoliberalism, and competition between state capital and private capital. She concluded by turning back to the U.S., citing Penny Pritzker’s transfer of her offshore accounts to a Delaware company benefiting her children after she became U.S. Secretary of Commerce. The question and answer session began the important work of mapping Harris’ and Hoang’s insights together within an analytic of racial capitalism. Hoang expressed uncertainty about how racial logic functions at her global scale of analysis, given that the ultra-rich she studies tend to identify as “global citizens.” It might be just here that Harris’ work on whiteness as property is applicable. The convergence of Hoang’s and Harris’ attention on legal codes and on the production of “frontiers” seem to be promising launch-pads for further conversation.

Map produced by Statista.[/caption] Hoang presented some of her data on investment in Vietnam, analyzing capital flows in and out of the country through a postcolonial lens. Vietnam’s economy is increasingly dominated by inter-Asian capital, which new competition between the U.S. and China and the regulatory outcomes of the 2008 financial crisis facilitate by allowing Vietnamese businesspeople and politicians to turn down Western money in favor of Asian investment. Nevertheless, U.S. investors still have a role to play in Vietnam’s speculative market: linking her presentation to Harris’, Hoang noted how “narratives of development bestow this precious boon” of profit, as illustrated by her interview excerpts with an American running speculative mining operations in Vietnam. In a context of “heterogeneous state-market relations,” access to Vietnamese markets requires connections with the Communist party. For foreign investors, Hoang contends, “the speculation is socialized through personal ties that shape markets and mitigate risk” especially by giving investors an apparently insider view of the market. However, behind the opacity of legal structures and information, foreign investors take the initial risk of expending large amounts of capital in “frontier” markets to discover a new “El Dorado,” but Vietnamese government officials are able to push them out once a market has been developed. Hoang describes this as a reconstitution of historical dynamics of globalization, as patterned by colonization, neoliberalism, and competition between state capital and private capital. She concluded by turning back to the U.S., citing Penny Pritzker’s transfer of her offshore accounts to a Delaware company benefiting her children after she became U.S. Secretary of Commerce. The question and answer session began the important work of mapping Harris’ and Hoang’s insights together within an analytic of racial capitalism. Hoang expressed uncertainty about how racial logic functions at her global scale of analysis, given that the ultra-rich she studies tend to identify as “global citizens.” It might be just here that Harris’ work on whiteness as property is applicable. The convergence of Hoang’s and Harris’ attention on legal codes and on the production of “frontiers” seem to be promising launch-pads for further conversation.