[On September 14, 2018 the Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory hosted Stacy Alaimo (UT Arlington) and Richard Keller (UW Madison) on a panel moderated by Zsuzsa Gille (Sociology) a part of the symposium Unnatural Disasters: Climate Change and the Limits of the Knowable. Below is a response to the panel by Brian F. O'Neill (Sociology).] Of Asphalt and Aquatic Snails: Tracing the Precarity of the Anthropocene Written by Brian O'Neill (Sociology) [gallery ids="1817,1818,1819" type="slideshow" orderby="rand"]

Dr. Zsuzsa Gille moderated the discussions (Image 1) by Dr. Alaimo (Image 2) and Dr. Keller (Image 3) at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign National Center for Supercomputing Applications. Images © Brian F. O’Neill

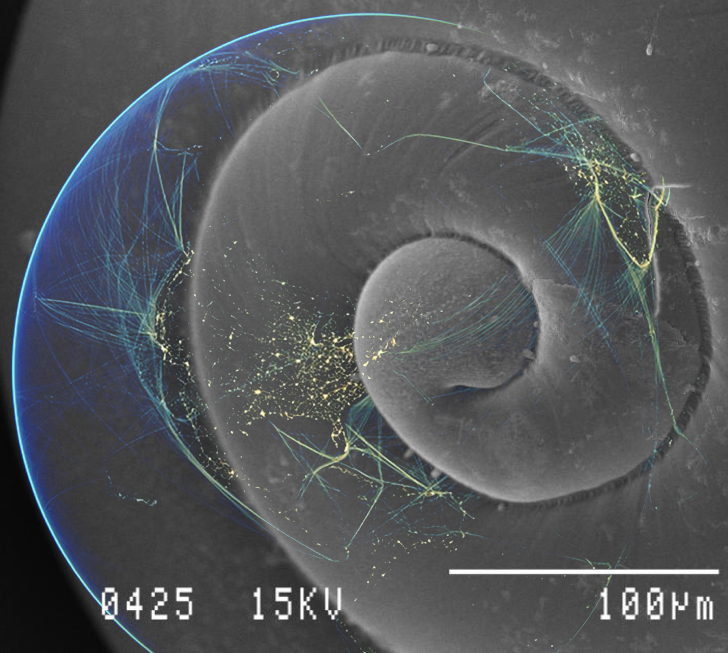

What can the seemingly disparate stories of urban heat islands and ocean acidification tell us about the Anthropocene? To what extent has the Earth shifted to a novel geologic epoch concomitant with human domination of the planet? Does the term “Anthropocene” itself lay too much emphasis on the human dimension of the processes involved? In what ways might this era be “more-than-human,” as Anna Tsing has argued, and be imbricating non-human forces and actors such as asphalt and aquatic snails? On Friday, September 14, 2018, Richard Keller and Stacy Alaimo provided an engaging discussion to explore and problematize contemporary thinking about the Anthropocene and rethink certain “natural disasters.” Each traced the often-precarious positions that humans hold in planet earth and across diverse societies. Perhaps surprisingly for a conference about climate change, their investigations do not lead us to a networked vision of the globe that seeks to encompass and assert a common human predicament; rather they speak to an Anthropos embedded in often unforeseen consequences, even the smallest moments of which have global importance. [caption id="attachment_1820" align="aligncenter" width="519"] Alaimo argued that scholars must consider “scale shifting,” to see humans and other species within the landscape if we are to develop a “trans-corporeal ecological political practice” that can converge with the world, various species, and vulnerabilities. Referencing Donna Haraway, she argued that the inundation of totalizing visions of the world seen from an omniscient point in outer-space is a “god’s eye trick,” which has the delusional effect of placing humans apart from their world. Composite image from Independent.co.uk and Nora.nerc.ac.uk.[/caption] Richard Keller began the event with his talk based on his 2015 book Fatal Isolation: The Devastating Paris Heat Wave of 2003. Keller argued that the issues of urban heat islands and heat waves remain extremely relevant. They represent “perfect storms” at the intersection of extreme heat, contemporary urban living, and social vulnerability in an age of unpredictable, often volatile climatic change. When nearly 15,000 people died in France in August of 2003, it was not merely from an anomalous climatic event. They died of extreme heat, but also of their precarious social positions. Furthermore, it is a problem of extreme heat, reaching 100°F (40°C) and higher during the day, but also of abnormally high night-tine temperatures (e.g. 72°F or 22°C), such that there was no abatement during the nights. The daily absorption of heat into the concrete, asphalt, and buildings during the long summer days kept the temperatures high even during the night. Indeed, Paris apartments are designed to retain heat during long winters, a design feature that exacerbated the problem of extreme heat. Although the human body can withstand very high temperatures, it must have at least some small reprieve from the heat periodically. In Paris in 2003, some residents were bombarded with heat day and night. Nighttime temperatures in some Paris apartments were reported as being as high as 110°F (43°C). Who is at risk? Keller explained that women and the elderly are especially vulnerable, but other crucial factors to consider are poverty and social isolation. Keller argued that in part due to the biopolitics of aging, whereby the elderly are construed as societal leeches, as having a certain lack of citizenship, they have increasingly become estranged from their social networks. Women who were elderly were less likely than men to be married, which made them more socially isolated. In addition, the lack of running water in older apartments, where bathrooms were located down the hall or on another floor, made it difficult for residents to find relief from the heat by taking a shower. Finally, social ties assist in one getting through such extreme events, and without them, cities face devastation like that of Paris in 2003. Rather than tracing social vulnerability along a horizontal geographical axis, Keller found that vulnerability during the Paris heat wave corresponded to a vertical one. Grey market rentals, with zinc roofs, lack of water, and cramped spaces facilitated the devastating outcomes that Paris experienced. In the end, though, Keller argued that we must be hopeful. Sociability and social networks among urban populations are the way to a better future. When people learn to rely on one another in their often dense urban environments, these “unnatural disasters” might be avoided or alleviated. Stacy Alaimo took the audience from the world of the contemporary city to the deep sea, where aquatic snails are dissolving due to ocean acidification. Ocean acidification is caused by a reduction in the pH of the ocean because of increased oceanic CO2 uptake from the atmosphere. Ocean acidification, she explained, occupies something of a twilight zone. It is a serious threat lurking silent and largely unseen by the world. In a literal sense, it lies outside of “the terrain of human concern” and remains “unthought” within a global climate change debate that prefers the imagery of the “god’s eye,” like a Google Earth globe seen from nowhere, but able to see everywhere. However, the dissolving calcium carbonite shells of aquatic snails show us the precarity and fragility of life. Alaimo argues that such problems should invite us to “scale up our thinking.” Alaimo stated that natural scientists and marine biologists are terrified by such observations, even though they are trained in a scientific paradigm of objectivity. These findings raise the question of how one can change the course of these events, rather than providing formal documentation of the catastrophe? Does ocean acidification, like climate change, like the energy crisis, etc. necessarily call for global transcendence? For Alaimo, the task is to build an environmentalism that at once encapsulates the multi-scalar and multi-species lives of these problems, while not obscuring environmental devastation. The problem with the god’s eye trick, and the concept of the Anthropocene is that one cannot simply “scale up,” and transcend in order to leave everything else behind. Instead, if these problems can be faced, it is through an engagement and intimacy with all earthly species and within the messy, material world that the Anthropos shares with other species. Both Keller and Alaimo showed that climate change is becoming manifest in novel and unexpected ways. However, such problems do not call for a transcendent globalized environmentalism. Rather, they call for attention to the corporeal manner by which humans become enveloped in myriad material processes. Indeed, in Anna Tsing’s keynote address she argued for studying the “feral,” unplanned effects and “betrayals” of nature to humans. Nature often proceeds in its own directions fed by the projects and programs of human ingenuity. Rather than being entranced by more typical scientific objects, creatures such as the aquatic snail or objects like the heat trapping asphalt of the big city can yield insights into the dynamics and agencies of the “more-than-human Anthropocene.”

Alaimo argued that scholars must consider “scale shifting,” to see humans and other species within the landscape if we are to develop a “trans-corporeal ecological political practice” that can converge with the world, various species, and vulnerabilities. Referencing Donna Haraway, she argued that the inundation of totalizing visions of the world seen from an omniscient point in outer-space is a “god’s eye trick,” which has the delusional effect of placing humans apart from their world. Composite image from Independent.co.uk and Nora.nerc.ac.uk.[/caption] Richard Keller began the event with his talk based on his 2015 book Fatal Isolation: The Devastating Paris Heat Wave of 2003. Keller argued that the issues of urban heat islands and heat waves remain extremely relevant. They represent “perfect storms” at the intersection of extreme heat, contemporary urban living, and social vulnerability in an age of unpredictable, often volatile climatic change. When nearly 15,000 people died in France in August of 2003, it was not merely from an anomalous climatic event. They died of extreme heat, but also of their precarious social positions. Furthermore, it is a problem of extreme heat, reaching 100°F (40°C) and higher during the day, but also of abnormally high night-tine temperatures (e.g. 72°F or 22°C), such that there was no abatement during the nights. The daily absorption of heat into the concrete, asphalt, and buildings during the long summer days kept the temperatures high even during the night. Indeed, Paris apartments are designed to retain heat during long winters, a design feature that exacerbated the problem of extreme heat. Although the human body can withstand very high temperatures, it must have at least some small reprieve from the heat periodically. In Paris in 2003, some residents were bombarded with heat day and night. Nighttime temperatures in some Paris apartments were reported as being as high as 110°F (43°C). Who is at risk? Keller explained that women and the elderly are especially vulnerable, but other crucial factors to consider are poverty and social isolation. Keller argued that in part due to the biopolitics of aging, whereby the elderly are construed as societal leeches, as having a certain lack of citizenship, they have increasingly become estranged from their social networks. Women who were elderly were less likely than men to be married, which made them more socially isolated. In addition, the lack of running water in older apartments, where bathrooms were located down the hall or on another floor, made it difficult for residents to find relief from the heat by taking a shower. Finally, social ties assist in one getting through such extreme events, and without them, cities face devastation like that of Paris in 2003. Rather than tracing social vulnerability along a horizontal geographical axis, Keller found that vulnerability during the Paris heat wave corresponded to a vertical one. Grey market rentals, with zinc roofs, lack of water, and cramped spaces facilitated the devastating outcomes that Paris experienced. In the end, though, Keller argued that we must be hopeful. Sociability and social networks among urban populations are the way to a better future. When people learn to rely on one another in their often dense urban environments, these “unnatural disasters” might be avoided or alleviated. Stacy Alaimo took the audience from the world of the contemporary city to the deep sea, where aquatic snails are dissolving due to ocean acidification. Ocean acidification is caused by a reduction in the pH of the ocean because of increased oceanic CO2 uptake from the atmosphere. Ocean acidification, she explained, occupies something of a twilight zone. It is a serious threat lurking silent and largely unseen by the world. In a literal sense, it lies outside of “the terrain of human concern” and remains “unthought” within a global climate change debate that prefers the imagery of the “god’s eye,” like a Google Earth globe seen from nowhere, but able to see everywhere. However, the dissolving calcium carbonite shells of aquatic snails show us the precarity and fragility of life. Alaimo argues that such problems should invite us to “scale up our thinking.” Alaimo stated that natural scientists and marine biologists are terrified by such observations, even though they are trained in a scientific paradigm of objectivity. These findings raise the question of how one can change the course of these events, rather than providing formal documentation of the catastrophe? Does ocean acidification, like climate change, like the energy crisis, etc. necessarily call for global transcendence? For Alaimo, the task is to build an environmentalism that at once encapsulates the multi-scalar and multi-species lives of these problems, while not obscuring environmental devastation. The problem with the god’s eye trick, and the concept of the Anthropocene is that one cannot simply “scale up,” and transcend in order to leave everything else behind. Instead, if these problems can be faced, it is through an engagement and intimacy with all earthly species and within the messy, material world that the Anthropos shares with other species. Both Keller and Alaimo showed that climate change is becoming manifest in novel and unexpected ways. However, such problems do not call for a transcendent globalized environmentalism. Rather, they call for attention to the corporeal manner by which humans become enveloped in myriad material processes. Indeed, in Anna Tsing’s keynote address she argued for studying the “feral,” unplanned effects and “betrayals” of nature to humans. Nature often proceeds in its own directions fed by the projects and programs of human ingenuity. Rather than being entranced by more typical scientific objects, creatures such as the aquatic snail or objects like the heat trapping asphalt of the big city can yield insights into the dynamics and agencies of the “more-than-human Anthropocene.”