[On October 10, the Unit for Criticism & Interpretive Theory hosted the lecture “Life After the Nation-State: Biopolitics and Beyond” as part of the Fall 2017 Modern Critical Theory Lecture Series. The speaker was Richard Keller (University of Wisconsin). Below is a response to the lecture from Michael Uhall (Political Science)]

Living with Biopolitical Nightmares Written by Michael Uhall (Political Science)Richard Keller raises an urgent question for everyone who wants to understand politics today: Is biopolitics obsolete?

When we talk about biopolitics, we’re talking not only about Michel Foucault’s ambiguous, yet remarkably fertile foray into the historical mutations of power. We’re also talking about an entire research paradigm addressing itself to the capacious and idiosyncratic set of cross-cutting political theories that both criticize and integrate questions about biology and the life sciences. Our biopolitical archives consist of diverse fields ranging from the history of eugenics and racialization to contemporary problematics in bioethics, the medical humanities, and posthumanism. For Foucault, biopolitics refers to the partial transformation of sovereign power into various modes of biopower. He describes sovereign power in terms of direct political authority over death – characterized by him as the power to let subjects live and to make subjects die – whereas biopower articulates itself through anthropometric regimes exemplifying the obverse power to make subjects live and to let subjects die.

Other theorists approach and expand upon biopolitics in a variety of ways: in terms of philosophical narratives exceeding the constraints of modernity’s advent (e.g., Giorgio Agamben, whose eight-volume Homo Sacer series maintains that an originary conceptual distinction between βίος, or bios, and ζωή, or zoe, leads to globally disastrous biopolitical consequences), as a potentially affirmative site of interaction between our largely deracinated political communities and the vital materiality of the body itself (e.g., Roberto Esposito, who describes biopolitical modernity in terms of a self-consuming immunitarian dynamic), and through a broadly postcolonial lens (e.g. Achille Mbembe, who argues that biopower generates itself by imposing conditions of material and social death upon colonial subjects).

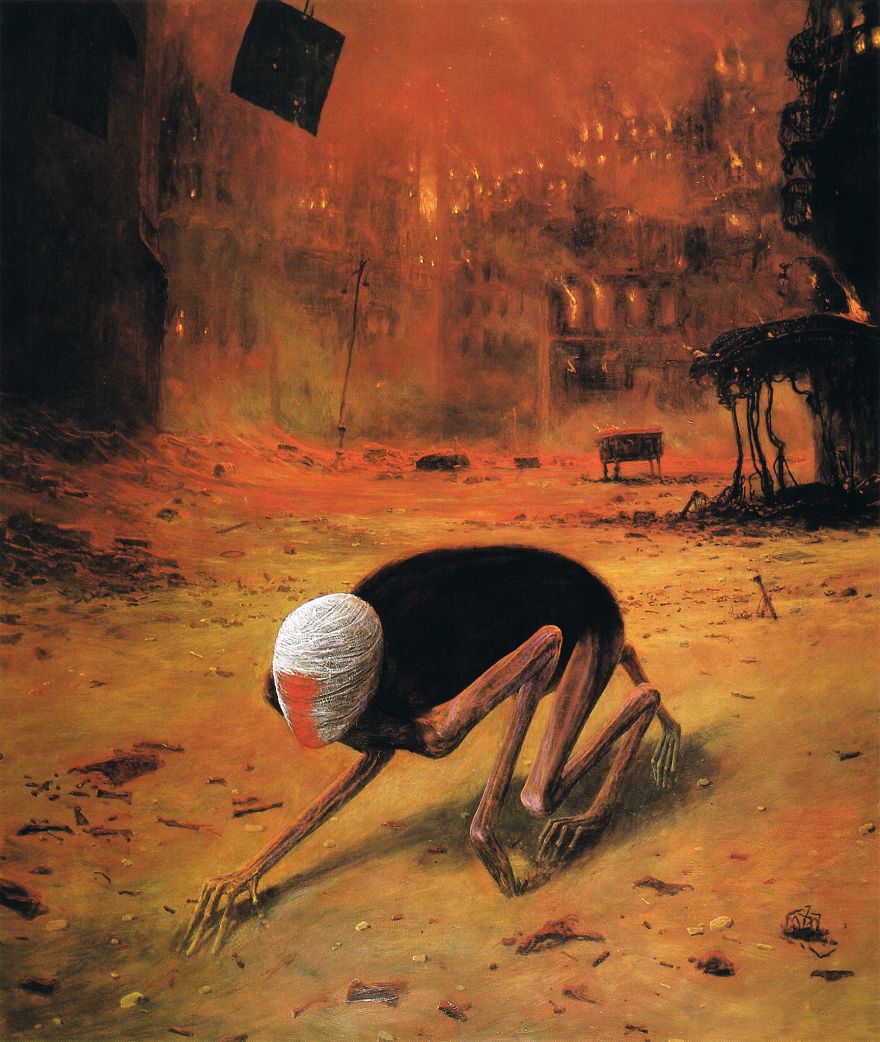

Figure 2: “Untitled” by Zdzisław Beksiński.[/caption]

Keller addresses some of these questions by examining several intriguing texts, all of which highlight the role and significance of liminality for any new biopolitics after the state. Specifically, he highlights recent work by John M. Willis, Debarati Sanyal, and Peter Redfield. In various ways, all of these scholars direct our attention to novel forms of biopolitics that exceed the “normal” conditions of state biopower. Indeed, these three examinations of refugeeism, religious securitarianism, and state failure raise the question of whether or not this strange thing we call biopolitics (it is by now almost a platitude that “biopolitics” is too polysemic to be defined) was ever as European, state-centric, or Western in its diagnostic structure as it appears to be in the Foucauldian discourse.

Something to consider, however – and Keller does discuss this – is the degree to which the fetish for privatization in modern Western culture inflects the domain of biopolitics as we find it. The concern here is that state failures prove vulnerable for corporate opportunism. However, it is certainly true that Foucault himself always sutured together biopolitics and political economy into various hideous historical hybrids of domination. Indeed, even Foucault’s late lectures on the “Birth of Biopolitics” largely concern themselves with the emergence of neoliberalism as cultural form and norm. In this regard, we should wonder about the degree to which biopolitical liminality offers avenues of escape rather than more opportunities for market segmentation. (Potential examples abound: compare Google’s provision of emergency balloons intended to provide Internet access in Puerto Rico with stories of United States soldiers calling firearm customer service hotlines for technical advice during the heat of battle.)

[caption id="attachment_1747" align="aligncenter" width="462"]

Figure 2: “Untitled” by Zdzisław Beksiński.[/caption]

Keller addresses some of these questions by examining several intriguing texts, all of which highlight the role and significance of liminality for any new biopolitics after the state. Specifically, he highlights recent work by John M. Willis, Debarati Sanyal, and Peter Redfield. In various ways, all of these scholars direct our attention to novel forms of biopolitics that exceed the “normal” conditions of state biopower. Indeed, these three examinations of refugeeism, religious securitarianism, and state failure raise the question of whether or not this strange thing we call biopolitics (it is by now almost a platitude that “biopolitics” is too polysemic to be defined) was ever as European, state-centric, or Western in its diagnostic structure as it appears to be in the Foucauldian discourse.

Something to consider, however – and Keller does discuss this – is the degree to which the fetish for privatization in modern Western culture inflects the domain of biopolitics as we find it. The concern here is that state failures prove vulnerable for corporate opportunism. However, it is certainly true that Foucault himself always sutured together biopolitics and political economy into various hideous historical hybrids of domination. Indeed, even Foucault’s late lectures on the “Birth of Biopolitics” largely concern themselves with the emergence of neoliberalism as cultural form and norm. In this regard, we should wonder about the degree to which biopolitical liminality offers avenues of escape rather than more opportunities for market segmentation. (Potential examples abound: compare Google’s provision of emergency balloons intended to provide Internet access in Puerto Rico with stories of United States soldiers calling firearm customer service hotlines for technical advice during the heat of battle.)

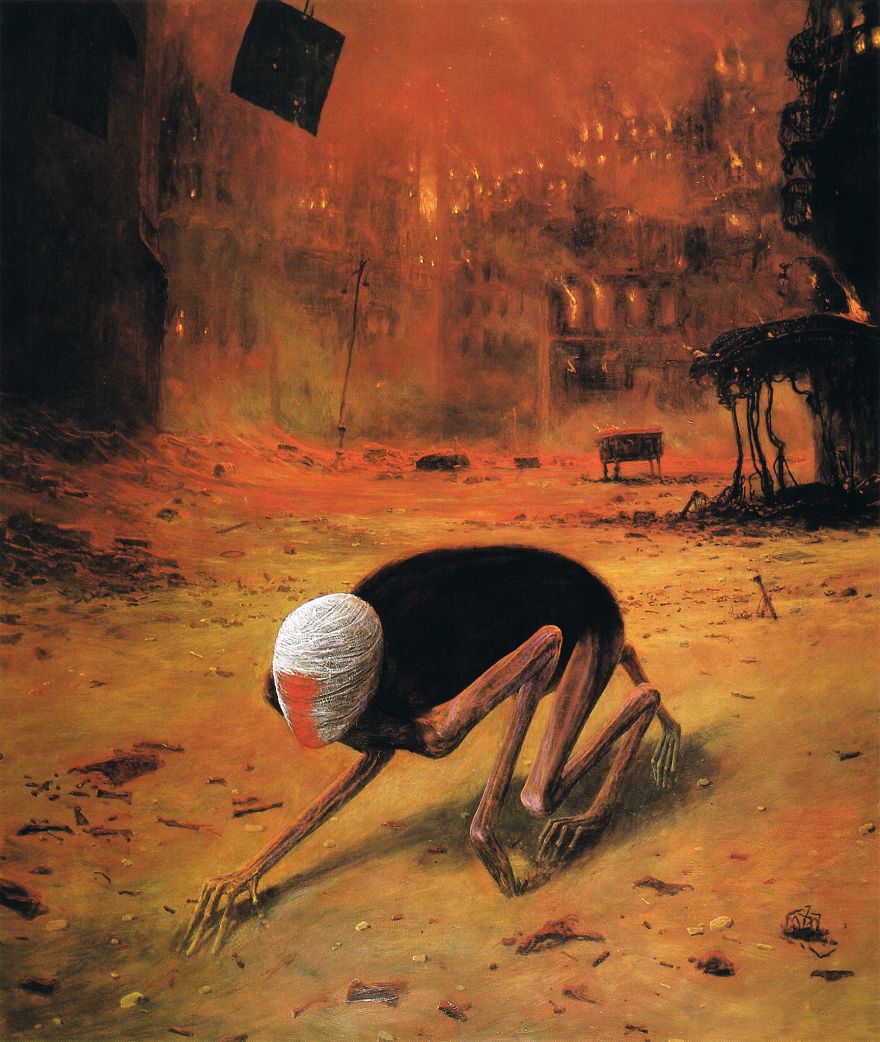

[caption id="attachment_1747" align="aligncenter" width="462"] Figure 3: “Untitled” by Zdzisław Beksiński.[/caption]

I’m reminded of nothing so much as K. W. Jeter’s nightmarish imaginary of future human subjects so biopolitically constrained that they are not even allowed to die – those he refers to in his dystopian cyberpunk novel Noir (1998) as “the indeadted.” The near-future world Jeter depicts could easily be ours, and in many ways, it is. Consider only the afterlife of e-waste and the practices of shipbreaking>. There is no functional government, no state that has not collapsed; the de facto sovereigns of this dying Earth are massive corporations that do not “rule” so much as they sequester themselves within the high temples of profit. All products and services come at a price no one can afford. Consider the following as a snapshot of that future, a future where the wolf flow of climax capitalism binds everyone and everything together in a surveilled economy of infinite productivity from which there no longer appears to be an escape:

Figure 3: “Untitled” by Zdzisław Beksiński.[/caption]

I’m reminded of nothing so much as K. W. Jeter’s nightmarish imaginary of future human subjects so biopolitically constrained that they are not even allowed to die – those he refers to in his dystopian cyberpunk novel Noir (1998) as “the indeadted.” The near-future world Jeter depicts could easily be ours, and in many ways, it is. Consider only the afterlife of e-waste and the practices of shipbreaking>. There is no functional government, no state that has not collapsed; the de facto sovereigns of this dying Earth are massive corporations that do not “rule” so much as they sequester themselves within the high temples of profit. All products and services come at a price no one can afford. Consider the following as a snapshot of that future, a future where the wolf flow of climax capitalism binds everyone and everything together in a surveilled economy of infinite productivity from which there no longer appears to be an escape:

Figure 1: “Untitled” by Zdzisław Beksiński.

Figure 1: “Untitled” by Zdzisław Beksiński.

Figure 2: “Untitled” by Zdzisław Beksiński.[/caption]

Keller addresses some of these questions by examining several intriguing texts, all of which highlight the role and significance of liminality for any new biopolitics after the state. Specifically, he highlights recent work by John M. Willis, Debarati Sanyal, and Peter Redfield. In various ways, all of these scholars direct our attention to novel forms of biopolitics that exceed the “normal” conditions of state biopower. Indeed, these three examinations of refugeeism, religious securitarianism, and state failure raise the question of whether or not this strange thing we call biopolitics (it is by now almost a platitude that “biopolitics” is too polysemic to be defined) was ever as European, state-centric, or Western in its diagnostic structure as it appears to be in the Foucauldian discourse.

Something to consider, however – and Keller does discuss this – is the degree to which the fetish for privatization in modern Western culture inflects the domain of biopolitics as we find it. The concern here is that state failures prove vulnerable for corporate opportunism. However, it is certainly true that Foucault himself always sutured together biopolitics and political economy into various hideous historical hybrids of domination. Indeed, even Foucault’s late lectures on the “Birth of Biopolitics” largely concern themselves with the emergence of neoliberalism as cultural form and norm. In this regard, we should wonder about the degree to which biopolitical liminality offers avenues of escape rather than more opportunities for market segmentation. (Potential examples abound: compare Google’s provision of emergency balloons intended to provide Internet access in Puerto Rico with stories of United States soldiers calling firearm customer service hotlines for technical advice during the heat of battle.)

[caption id="attachment_1747" align="aligncenter" width="462"]

Figure 2: “Untitled” by Zdzisław Beksiński.[/caption]

Keller addresses some of these questions by examining several intriguing texts, all of which highlight the role and significance of liminality for any new biopolitics after the state. Specifically, he highlights recent work by John M. Willis, Debarati Sanyal, and Peter Redfield. In various ways, all of these scholars direct our attention to novel forms of biopolitics that exceed the “normal” conditions of state biopower. Indeed, these three examinations of refugeeism, religious securitarianism, and state failure raise the question of whether or not this strange thing we call biopolitics (it is by now almost a platitude that “biopolitics” is too polysemic to be defined) was ever as European, state-centric, or Western in its diagnostic structure as it appears to be in the Foucauldian discourse.

Something to consider, however – and Keller does discuss this – is the degree to which the fetish for privatization in modern Western culture inflects the domain of biopolitics as we find it. The concern here is that state failures prove vulnerable for corporate opportunism. However, it is certainly true that Foucault himself always sutured together biopolitics and political economy into various hideous historical hybrids of domination. Indeed, even Foucault’s late lectures on the “Birth of Biopolitics” largely concern themselves with the emergence of neoliberalism as cultural form and norm. In this regard, we should wonder about the degree to which biopolitical liminality offers avenues of escape rather than more opportunities for market segmentation. (Potential examples abound: compare Google’s provision of emergency balloons intended to provide Internet access in Puerto Rico with stories of United States soldiers calling firearm customer service hotlines for technical advice during the heat of battle.)

[caption id="attachment_1747" align="aligncenter" width="462"] Figure 3: “Untitled” by Zdzisław Beksiński.[/caption]

I’m reminded of nothing so much as K. W. Jeter’s nightmarish imaginary of future human subjects so biopolitically constrained that they are not even allowed to die – those he refers to in his dystopian cyberpunk novel Noir (1998) as “the indeadted.” The near-future world Jeter depicts could easily be ours, and in many ways, it is. Consider only the afterlife of e-waste and the practices of shipbreaking>. There is no functional government, no state that has not collapsed; the de facto sovereigns of this dying Earth are massive corporations that do not “rule” so much as they sequester themselves within the high temples of profit. All products and services come at a price no one can afford. Consider the following as a snapshot of that future, a future where the wolf flow of climax capitalism binds everyone and everything together in a surveilled economy of infinite productivity from which there no longer appears to be an escape:

Figure 3: “Untitled” by Zdzisław Beksiński.[/caption]

I’m reminded of nothing so much as K. W. Jeter’s nightmarish imaginary of future human subjects so biopolitically constrained that they are not even allowed to die – those he refers to in his dystopian cyberpunk novel Noir (1998) as “the indeadted.” The near-future world Jeter depicts could easily be ours, and in many ways, it is. Consider only the afterlife of e-waste and the practices of shipbreaking>. There is no functional government, no state that has not collapsed; the de facto sovereigns of this dying Earth are massive corporations that do not “rule” so much as they sequester themselves within the high temples of profit. All products and services come at a price no one can afford. Consider the following as a snapshot of that future, a future where the wolf flow of climax capitalism binds everyone and everything together in a surveilled economy of infinite productivity from which there no longer appears to be an escape: