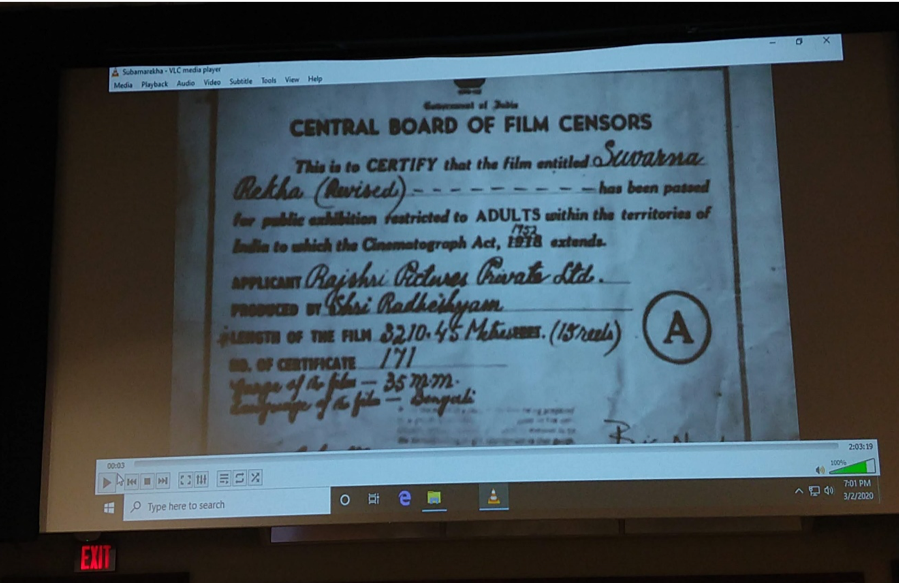

[On March 7, 2020, the Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory hosted a film screening of Ritwik Ghatak's Subarnarekha (1962) by visiting scholar Moinak Biswas (Film Studies, Jadavpur University). Below is a response by Susmita Das (Institute of Communications Research).] Thinking (and Teaching) History through Film Form Written by Susmita Das (Institute of Communications Research) As we settled into our seats in the Armory theater, the movie was paused on the film’s certificate of exhibition. Subarnarekha or Suvarna Rekha was released as an “A” film in 1962, meaning the film was intended for Adult audiences. But what mature content could a Bengali film set against the Partition contain? I wondered. [caption id="attachment_2090" align="alignnone" width="899"] Image taken by the author at the film screening[/caption] “This is one of the most violent films that people had seen in Indian cinema,” Prof. Moinak Biswas began. [caption id="attachment_2093" align="align-left" width="238"]

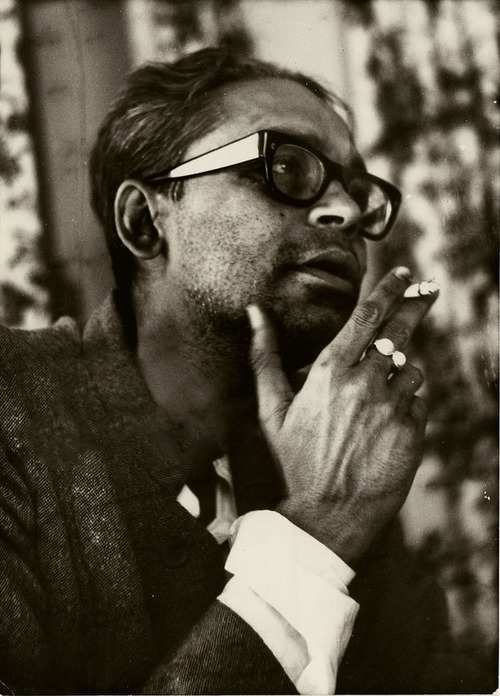

Image taken by the author at the film screening[/caption] “This is one of the most violent films that people had seen in Indian cinema,” Prof. Moinak Biswas began. [caption id="attachment_2093" align="align-left" width="238"] Image of Ritwik Ghatak[/caption] Ritwik Ghatak (1925-1976), the director of Subarnarekha, was a visionary of Bengali and Indian cinema whose films responded to the Partition of India in 1947 through a trilogy of which Subarnarekha was the third and final part. Ghatak’s films were misunderstood by film critics and attacked for “professing despair” at a time when his leftist contemporaries believed that a socialist utopia was right there (as Prof. Biswas explained in his lecture the next day). Ghatak responded to his critics in 1966 with two essays in Bengali. In these essays (translated into English by Prof. Biswas), Ghatak not only mourns his critics’ gross misinterpretation of Subarnarekha’s message, but also the death of film criticism:

Image of Ritwik Ghatak[/caption] Ritwik Ghatak (1925-1976), the director of Subarnarekha, was a visionary of Bengali and Indian cinema whose films responded to the Partition of India in 1947 through a trilogy of which Subarnarekha was the third and final part. Ghatak’s films were misunderstood by film critics and attacked for “professing despair” at a time when his leftist contemporaries believed that a socialist utopia was right there (as Prof. Biswas explained in his lecture the next day). Ghatak responded to his critics in 1966 with two essays in Bengali. In these essays (translated into English by Prof. Biswas), Ghatak not only mourns his critics’ gross misinterpretation of Subarnarekha’s message, but also the death of film criticism:

“There was not the slightest intention in my mind to profess ‘despair.’ I have tried to capture the great crisis that… has come to take on monstrous proportions. The first casualty of that [crisis] is our sensitivity. It has been gradually benumbed; and I wanted to strike at that.”

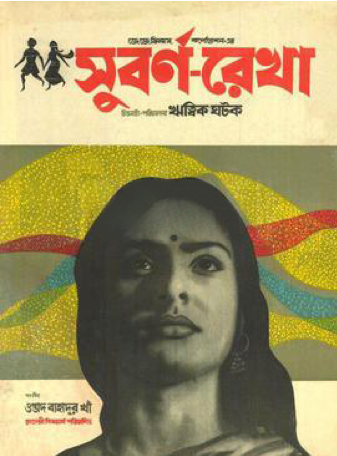

Indeed, Subarnarekha strikes. In the final act of the film, Ishwar lands at his sister Sita’s house after years of separation as a customer for paid sex; the magnitude of political and social violence impregnating this moment is overwhelming. [caption id="attachment_2094" align="align-right" width="337"] Sita in Subarnarekha Movie Poster[/caption] Sita throws herself on a boti (a vegetable cutter) and ends her life. Sita’s suicide is what Prof. Biswas describes as one of the most violent acts shown in Indian cinema and which earned the film its A certificate. The sequence is an achievement in blocking and staging that film and media scholars will recognize in the use of unconventional camera placements, movements, and focuses to visually depict the act through implication rather than through dramatization. Ghatak, with his cinematographer and editor, stage the sequence using oblique angles, extreme close ups, harsh shadows, in-focus and out-of-focus shots, peculiar pans and tracks, non-diegetic score, and – my favorite – asynchronous sounds, to jolt us out of our numbness. [Start time: 1:45:30 (6330s) - End time: 1:49:56 (6596s)] Revealing the climax of the film at the start of his lecture, Prof. Biswas instructs us to watch for Ghatak’s use of different conventions in narrative transition, stating that this is what makes Ghatak a modernist while qualifying, “but not in the European sense.” Prof. Biswas explains that Ghatak employs three different conventions to intertwine linear storytelling with historical time. In Subarnarekha, Ghatak uses “scrolls,” a simple technique borrowed from English chronicle plays to convey the passage of linear time in the characters’ lives. The scrolls break up the narrative into three episodes; the episodes are brought into conversation with historical time through unlikely “coincidences” and odd insertions of mythic characters, verses, words and phrases lifted directly from the Upanishads (ancient Sanskrit texts), Sishutirtha, a poem by Rabindranath Tagore, and the words uttered by Mahatma Gandhi at the moment of his death. In the above clip, the source-less “hey Ram” (1:48:20 or 6500s) is one such example. While Subarnarekha is renowned as part of the Partition Trilogy (a term better suited to the economics of film promotion, perhaps), it is not about Partition only, Prof. Biswas contends. The “great crisis,” taking on “monstrous proportions,” was homelessness, a crisis so great in magnitude that it cannot be shown as one event alone—which, Prof. Biswas argues, Ghatak works out in Subarnarekha with film form and content, convention and technique. Sita’s suicide, therefore, is only a sublimation of the complete derailment of lives that occurs as an effect of multiple historical tragedies. Prof. Biswas presents Ghatak’s Subarnarekha almost as a didactic text that teaches us to think history when we think of what constitutes “ordinary lives in the wake of Partition” (or a loss of home) and what makes up “the epochal resonance of homelessness in human experience.” Ghatak’s Subarnarekha advances a dialect to speak of that experience, working out a form that can visualize a violence of monstrous proportions.

Sita in Subarnarekha Movie Poster[/caption] Sita throws herself on a boti (a vegetable cutter) and ends her life. Sita’s suicide is what Prof. Biswas describes as one of the most violent acts shown in Indian cinema and which earned the film its A certificate. The sequence is an achievement in blocking and staging that film and media scholars will recognize in the use of unconventional camera placements, movements, and focuses to visually depict the act through implication rather than through dramatization. Ghatak, with his cinematographer and editor, stage the sequence using oblique angles, extreme close ups, harsh shadows, in-focus and out-of-focus shots, peculiar pans and tracks, non-diegetic score, and – my favorite – asynchronous sounds, to jolt us out of our numbness. [Start time: 1:45:30 (6330s) - End time: 1:49:56 (6596s)] Revealing the climax of the film at the start of his lecture, Prof. Biswas instructs us to watch for Ghatak’s use of different conventions in narrative transition, stating that this is what makes Ghatak a modernist while qualifying, “but not in the European sense.” Prof. Biswas explains that Ghatak employs three different conventions to intertwine linear storytelling with historical time. In Subarnarekha, Ghatak uses “scrolls,” a simple technique borrowed from English chronicle plays to convey the passage of linear time in the characters’ lives. The scrolls break up the narrative into three episodes; the episodes are brought into conversation with historical time through unlikely “coincidences” and odd insertions of mythic characters, verses, words and phrases lifted directly from the Upanishads (ancient Sanskrit texts), Sishutirtha, a poem by Rabindranath Tagore, and the words uttered by Mahatma Gandhi at the moment of his death. In the above clip, the source-less “hey Ram” (1:48:20 or 6500s) is one such example. While Subarnarekha is renowned as part of the Partition Trilogy (a term better suited to the economics of film promotion, perhaps), it is not about Partition only, Prof. Biswas contends. The “great crisis,” taking on “monstrous proportions,” was homelessness, a crisis so great in magnitude that it cannot be shown as one event alone—which, Prof. Biswas argues, Ghatak works out in Subarnarekha with film form and content, convention and technique. Sita’s suicide, therefore, is only a sublimation of the complete derailment of lives that occurs as an effect of multiple historical tragedies. Prof. Biswas presents Ghatak’s Subarnarekha almost as a didactic text that teaches us to think history when we think of what constitutes “ordinary lives in the wake of Partition” (or a loss of home) and what makes up “the epochal resonance of homelessness in human experience.” Ghatak’s Subarnarekha advances a dialect to speak of that experience, working out a form that can visualize a violence of monstrous proportions.