[On October 29, 2012 the Department of Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese hosted a colloquium with Ignacio Sánchez Prado (Washington University). His talk, "Alfonso Cuarón, Carlos Reygadas and the End of National Cinema in Mexico," is discussed by Sarah M. West a graduate affiliate in Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese.]

Sarah M. West (Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese)

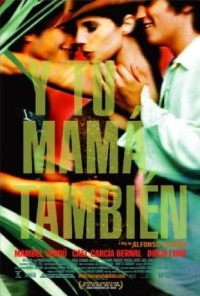

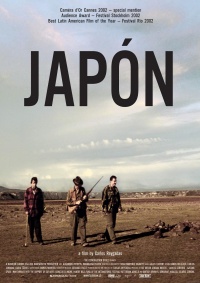

In this colloquium, Ignacio Sánchez Prado presented on the theme from his forthcoming book, tentatively entitled Mexican Film in the Age of NAFTA, about the perpetuation of Mexican nationalism being undone by late-20th century Mexican cinema. He exemplified this through the analysis of two Mexican films: Japón (2002) by cinematographer Carlos Reygadas and Y tu mamá también (2001) by Alfonso Cuarón.

Y tu mamá también examplifies the reconfiguration of a Mexican polity under the stresses of a neoliberal state. Sánchez Prado identified such features as an emerging middle class, lacking "Mexicanness," as well as a new positioning of Mexico in "Global Art Cinema." He posited that the film makes use of the disembodied, male voice-over as the only position for the discussion of politics in the film, a device that places the realm of politics outside of the characters' reach and the film's plot. For Sánchez Prado, this is proof that it has become impossible to inscribe politics in the actual fabric of a film in the neoliberal moment. However, the contradictions and inequalities of neoliberalism are represented in a desire to represent Mexico as commodifiable, an idea toward which filmmaker Cuarón seems sympathetic as a producer of commercial cinema.

Sánchez Prado understands the blindness of the urban middle class to the provincia and of the lack of memory of any national identity that does not involve Mexican elite as part of a new relationship between cinema and the neoliberal polity. The new Mexican national cinema is not concerned with representing the reality of the nation or in constructing a homogenous national discourse. Rather, the new Mexican national cinema constructs an allegory of neoliberal subjectivity, proving, according to Sánchez Prado, the exhaustion of the construct of "the nation" to represent Mexico's polity.

Reygadas' movie, Japón, was interpreted by Sánchez Prado in a somewhat similar way. He identifies the presentation of both aesthetics in the Mexican provincia and the manipulation of audience affect and vision as two recurring themes in Reygadas' cinematics. The cinematographer inserts his work into a genealogy of art cinema producers: by mimicking their camera work and using non-professional actors, he connects his film to the practices of a global community of art cinema makers. Such techniques stray from traditional Mexican cinema in which landscapes are used to embed ideological meaning. Reygadas elongates shots of landscape to induce boredom in viewers, enabling them to view the scene more critically. As a result, Mexicanness is suspended, as is reflected in the title of the film (English translation: Japan). This new, global effect allows Mexican cinema to be included in the international art cinema niche. Reygadas erodes national signifiers through boredom and other affectual manipulations until all such signifiers are stripped away and the viewer can extract no such meanings from the scene. This perpetuates the neoliberal ideology of Mexico for both national and international circulation. Simultaneously it creates interesting and productive spaces for the commodification of Mexican landscapes for a new Mexican art cinema niche.

At the conclusion of the colloquium, the audience directed several questions to Sánchez Prado that addressed concern over the relationship of form and politics and of genuine political expression in a neoliberal setting. The presenter offered a useful view of late-20th-century Mexican cinema reflecting the current political situation that Mexico is experiencing in the age of neoliberal ideology and policy. The new Mexican art cinema has filled this role because “nationalism” is no longer sufficient to represent the Mexican body politic.