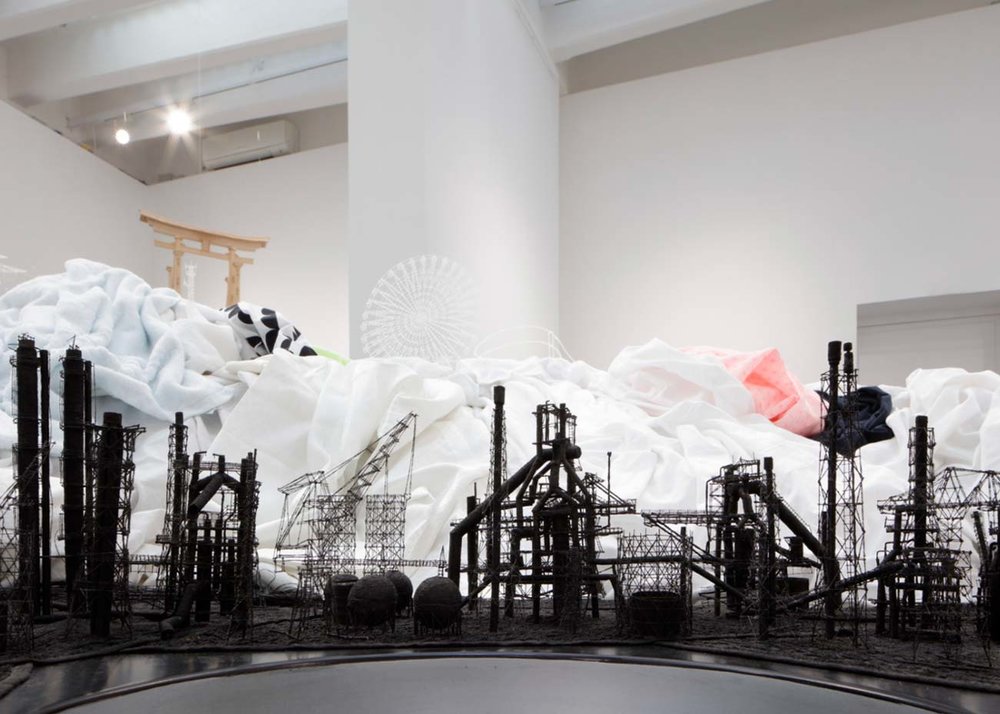

[On March 29, 2019, the Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory hosted the panel "Undermining Indigenous Sovereignty: Techniques of Wastelanding and Welfare Provision," which was chaired by Jenny Davis (UIUC) as part of the Racial Capitalism symposium. The panel featured the following talks: "Settler Colonialism's Hiroshima," by Iyko Day (Mt. Holyoke) and "'There for the Taking': Colonial Entitlement and the Relations of Reproduction," by Alyosha Goldstein (U New Mexico). Below is a response by Austin D. Hoffman (Anthropology).] Defining the Social Technologies of Non-Worlding: Challenging Nuclear Hegemony and Neoliberal Colorblindness Written by Austin D. Hoffman (Anthropology) As Frantz Fanon wrote in his seminal work The Wretched of the Earth, “Marxist analysis should always be slightly stretched every time we have to do with the colonial problem.” This analytical stretching is precisely what Professors Iyko Day and Alyosha Goldstein employed in their panel entitled “Undermining Indigenous Sovereignty: Techniques of Wastelanding and Welfare Provision,” for the Unit’s Racial Capitalism symposium. Both scholars draw from neo-Marxist theories to highlight the ongoing processes of dispossession and accumulation that are constitutive of settler colonial racial capitalism. In doing so, their presentations echo Patrick Wolfe’s pithy statement—now almost taken as a truism—that settler colonialism “is a structure not an event.” Day began her talk, “Settler Colonialism’s Hiroshima,” by taking up the question of how the 1945 atomic bombings in Japan structure our knowledge of a post-war, nuclearized world, and how the dominant perceptions of this event rely on forms of “colonial unknowing,” a concept that Goldstein helped theorize. By mapping capitalism’s logistical networks, she traces a “supply chain of violence” back to the sites of accumulation that allowed for the production of these weapons of mass destruction in the first place. Some of these sites include the Belgian Congo, the Northwest Territories in Canada, and Navajo communities in New Mexico. These areas have been disastrously affected by uranium mining, radioactivity, and nuclear testing. Uranium mining in particular requires hyper-exploitable and disposable labor; yet even though Indigenous lands, resources, and workers are essential to nuclear modernity, they are construed as non-places and non-persons by the settler colonial state. While connecting these geopolitical dots, Day uses Robin Kelley’s critique of Wolfe to call attention to the fact that settler colonial studies has often obscured or entirely erased the experiences of African peoples. Citing the example of South Africa, Kelley challenges Wolfe’s assertion that settlers only wanted Native land and not their labor, and argues that proletarianization can also be a fundamental goal of the settler state. As he puts it, “[t]hey wanted the land and the labor, but not the people.” Day’s examples of Indigenous nuclear non-sites also demonstrate how colonial land theft and capitalistic worker exploitation operate in tandem to create “radioactive wastelands of logistical violence.” It is here that she revisits Marx’s theory of primitive accumulation, as described in Capital. More specifically she uses Rosa Luxemburg’s reformulation of primitive accumulation as a continuing element of capitalist expansion, rather than a discrete and temporary phase of capitalism as Marx theorized. By viewing these radioactive wastelands as new frontiers of extraction, Day shows how imperial capitalism’s logistical operations function as “the handmaiden of a perfected, systematic, contemporary form of primitive accumulation.” Part of what allows this ongoing dispossession is the symbolic power of uranium itself. Day illustrates this through Ryan Coogler’s wildly popular film Black Panther. In the film, the fictitious metal vibranium, which serves as a metaphor for uranium, is the source of immense magical and deadly powers. The film fits in with a long tradition of popular discourse about uranium that views the chemical element as an almost otherworldly and limitless fount of energy. The fact that the hero Black Panther’s powers emanate from it is indicative of, as Day says, the “hegemonic ability of uranium to manufacture consent as humanity’s green energy savior, while simultaneously being the apocalyptic symbol of military annihilation.” [caption id="attachment_1910" align="aligncenter" width="550"] From Allan deSouza's Terrain series (a slide from Day's lecture). Entitled Terrain 8. Medium: Hair, eyelashes, and ear wax. Source: http://allandesouza.com/index.php?/photography/terrain00/.[/caption] How can such a magical hegemony be challenged? How might the violent non-worlding of Indigenous peoples and the occlusion of living labor be subverted? Day attempts to do this by examining Asian and Asian-American visual culture. By connecting nuclear non-sites to the works of multi-media artist Allan deSouza and sculptor Takahiro Iwasaki, Day endeavors to rethink these spaces and histories outside of anthropocene cataclysms. Popular media of nuclear disasters and fallout (what some refer to as “ruin porn”) rarely includes human beings. Consider the iconic image of the mushroom cloud rising over Hiroshima, the eerie deserted cityscapes of the Chernobyl exclusion zone, or even the “blighted” neighborhoods of post-industrial Detroit. They all give the impression of a gradual process of degradation devoid of human agency and labor; they serve as abstractions perpetuating what Marx called “the phantom-like objectivity of capital.” Both deSouza and Iwasaki reveal the abstractions of capitalist production by using forms of detritus. In deSouza’s Terrain series, he uses his own bodily detritus—eyelashes, ear wax, nail clippings, and pubic hair—as a medium to construct grotesque landscapes that subtly satirize the masculinist and nationalist motifs in the art and photography of American 19th and 20th century artists like Thomas Cole and Ansel Adams (Day extensively unpacks the “romantic anticapitalist” ethos of these American icons in her book 2016 book Alien Capital). Through a less intimate but no less provocative medium, Iwasaki uses domestic detritus like towels, brushes, thread, duct tape, dust, and other mundane items to construct architectural miniatures of landmarks and sceneries that not only mirror the imagery of desertion and disaster, but also preserve Japan’s industrial past. [caption id="attachment_1909" align="aligncenter" width="1000"]

From Allan deSouza's Terrain series (a slide from Day's lecture). Entitled Terrain 8. Medium: Hair, eyelashes, and ear wax. Source: http://allandesouza.com/index.php?/photography/terrain00/.[/caption] How can such a magical hegemony be challenged? How might the violent non-worlding of Indigenous peoples and the occlusion of living labor be subverted? Day attempts to do this by examining Asian and Asian-American visual culture. By connecting nuclear non-sites to the works of multi-media artist Allan deSouza and sculptor Takahiro Iwasaki, Day endeavors to rethink these spaces and histories outside of anthropocene cataclysms. Popular media of nuclear disasters and fallout (what some refer to as “ruin porn”) rarely includes human beings. Consider the iconic image of the mushroom cloud rising over Hiroshima, the eerie deserted cityscapes of the Chernobyl exclusion zone, or even the “blighted” neighborhoods of post-industrial Detroit. They all give the impression of a gradual process of degradation devoid of human agency and labor; they serve as abstractions perpetuating what Marx called “the phantom-like objectivity of capital.” Both deSouza and Iwasaki reveal the abstractions of capitalist production by using forms of detritus. In deSouza’s Terrain series, he uses his own bodily detritus—eyelashes, ear wax, nail clippings, and pubic hair—as a medium to construct grotesque landscapes that subtly satirize the masculinist and nationalist motifs in the art and photography of American 19th and 20th century artists like Thomas Cole and Ansel Adams (Day extensively unpacks the “romantic anticapitalist” ethos of these American icons in her book 2016 book Alien Capital). Through a less intimate but no less provocative medium, Iwasaki uses domestic detritus like towels, brushes, thread, duct tape, dust, and other mundane items to construct architectural miniatures of landmarks and sceneries that not only mirror the imagery of desertion and disaster, but also preserve Japan’s industrial past. [caption id="attachment_1909" align="aligncenter" width="1000"] From Takahiro Iwasaki's Out of Disorder series. Entitled Out of Disorder (Mountains and Sea). Medium: Sheets, towels, thread, dust. Source: https://japanobjects.com/features/takahiro-iwasaki.[/caption] Day argues that these artistic works recast the wasteland as a vision of the real, thus decommodifying and defetishizing it. deSouza’s queering of the idyllic colonial landscape and Iwasaki’s repurposing of anthropocene refuse serve as visual allegories of capitalist abstraction. Viewed together, they recenter the human labor at the heart of nuclear modernity, as well as the lives it continues to ravage. Their art demystifies the capitalist social relations that present themselves as opaque and objective, functioning, in Day’s words, as “repositories of the intimate, fleshy and filthy effects of historical processes that we have forgotten.” Goldstein’s research also endeavors to unravel the tortuous logics of colonialism in the present. Like Day, he focuses on Indigenous dispossession, but does so by analyzing sites of social reproduction rather than sites of accumulation. His paper, “There for the Taking: Colonial Entitlement and the Relations of Reproduction,” takes a Marxist-feminist approach to explore the “perpetual remaking” of gendered and racialized capitalist social relations, with a particular focus on how certain forms of social reproduction also reproduce a chronic vulnerability to violence and violation. Goldstein examines American adoption and foster care systems as imperialist and white supremacist social technologies that preempt Indigenous futurity. He points out that he is not speaking against the legitimacy of adoption and foster care in general, but only insofar as they operate as an “ensemble of colonial practices.” His paper centers on the 2018 Brackeen v Zinke decision in the US District Court for the Northern District of Texas, which granted custody of a two-year-old Navajo-Cherokee boy to a white couple against the wishes of the Navajo Nation. This case is poised to undermine the protections of the 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA). As the Bureau of Indian Affairs states, this act was instituted to “protect the best interest of Indian children and to promote the stability and security of Indian tribes and families.” But right-wing advocacy groups such as the Goldwater Institute have challenged the constitutionality of ICWA by claiming that it is a “racist” law that grants “special rights” to tribal nations, which they allege undermines US sovereignty. Even though the Brackeens won their case, several other states and couples have since joined them to pursue further litigation in an effort to declare the entirety of ICWA as unconstitutional. [caption id="attachment_1908" align="aligncenter" width="449"]

From Takahiro Iwasaki's Out of Disorder series. Entitled Out of Disorder (Mountains and Sea). Medium: Sheets, towels, thread, dust. Source: https://japanobjects.com/features/takahiro-iwasaki.[/caption] Day argues that these artistic works recast the wasteland as a vision of the real, thus decommodifying and defetishizing it. deSouza’s queering of the idyllic colonial landscape and Iwasaki’s repurposing of anthropocene refuse serve as visual allegories of capitalist abstraction. Viewed together, they recenter the human labor at the heart of nuclear modernity, as well as the lives it continues to ravage. Their art demystifies the capitalist social relations that present themselves as opaque and objective, functioning, in Day’s words, as “repositories of the intimate, fleshy and filthy effects of historical processes that we have forgotten.” Goldstein’s research also endeavors to unravel the tortuous logics of colonialism in the present. Like Day, he focuses on Indigenous dispossession, but does so by analyzing sites of social reproduction rather than sites of accumulation. His paper, “There for the Taking: Colonial Entitlement and the Relations of Reproduction,” takes a Marxist-feminist approach to explore the “perpetual remaking” of gendered and racialized capitalist social relations, with a particular focus on how certain forms of social reproduction also reproduce a chronic vulnerability to violence and violation. Goldstein examines American adoption and foster care systems as imperialist and white supremacist social technologies that preempt Indigenous futurity. He points out that he is not speaking against the legitimacy of adoption and foster care in general, but only insofar as they operate as an “ensemble of colonial practices.” His paper centers on the 2018 Brackeen v Zinke decision in the US District Court for the Northern District of Texas, which granted custody of a two-year-old Navajo-Cherokee boy to a white couple against the wishes of the Navajo Nation. This case is poised to undermine the protections of the 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA). As the Bureau of Indian Affairs states, this act was instituted to “protect the best interest of Indian children and to promote the stability and security of Indian tribes and families.” But right-wing advocacy groups such as the Goldwater Institute have challenged the constitutionality of ICWA by claiming that it is a “racist” law that grants “special rights” to tribal nations, which they allege undermines US sovereignty. Even though the Brackeens won their case, several other states and couples have since joined them to pursue further litigation in an effort to declare the entirety of ICWA as unconstitutional. [caption id="attachment_1908" align="aligncenter" width="449"] Goldwater Institute Logo. The Goldwater Institute is a right-wing think tank leading the litigation against ICWA. It was founded in 1988, named in honor of the arch-conservative senator Barry Goldwater, who voted against the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[/caption] There are obvious parallels between the attacks on ICWA and those against Affirmative Action and other anti-discrimination laws. As Goldstein pointed out, proponents of neoliberal colorblindness attempt to destroy institutional protections against racism and colonial dispossession through a litigious alchemy that somehow makes these same protections the source of racism and colonial dispossession. He has previously written about how these logics are premised on the idea that “specifying indigenous rights would contaminate the universal rights of humankind with a corrosive particularity.” Goldstein situates the efforts to declare ICWA as unconstitutional alongside other settler colonial biopolitical weapons such as boarding schools, which “insinuate settler futurity over Indigenous life and social relations.” Since Native American children are placed in foster care at disproportionate rates, adoption policies that favor placement with heteronormative white families serve to erode and eliminate the kinship systems and sociohistorical continuity of First Nations. ICWA was passed as a defensive measure against this slow assimilationist violence. While Goldstein acknowledged in the Q&A that ICWA is problematic in some ways because it reinscribes biological frames of tribal citizenship, he is clear that litigation against ICWA is a transparent endeavor to preserve and extend the conditions of social reproduction of capitalism, private property relations, and normative sociality. [caption id="attachment_1911" align="aligncenter" width="360"]

Goldwater Institute Logo. The Goldwater Institute is a right-wing think tank leading the litigation against ICWA. It was founded in 1988, named in honor of the arch-conservative senator Barry Goldwater, who voted against the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[/caption] There are obvious parallels between the attacks on ICWA and those against Affirmative Action and other anti-discrimination laws. As Goldstein pointed out, proponents of neoliberal colorblindness attempt to destroy institutional protections against racism and colonial dispossession through a litigious alchemy that somehow makes these same protections the source of racism and colonial dispossession. He has previously written about how these logics are premised on the idea that “specifying indigenous rights would contaminate the universal rights of humankind with a corrosive particularity.” Goldstein situates the efforts to declare ICWA as unconstitutional alongside other settler colonial biopolitical weapons such as boarding schools, which “insinuate settler futurity over Indigenous life and social relations.” Since Native American children are placed in foster care at disproportionate rates, adoption policies that favor placement with heteronormative white families serve to erode and eliminate the kinship systems and sociohistorical continuity of First Nations. ICWA was passed as a defensive measure against this slow assimilationist violence. While Goldstein acknowledged in the Q&A that ICWA is problematic in some ways because it reinscribes biological frames of tribal citizenship, he is clear that litigation against ICWA is a transparent endeavor to preserve and extend the conditions of social reproduction of capitalism, private property relations, and normative sociality. [caption id="attachment_1911" align="aligncenter" width="360"] Parents gathered in support for the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) at a rally in South Dakota, 2013. Source: https://www.indianz.com/News/2013/03/29/native-sun-news-rally-in-suppo.asp[/caption] This talk resonated with Day’s by showing that the violent dispossession of Indigenous peoples is based on a denial of claims to both land and personhood. Indeed, for the colonizer, the legal doctrine of Fillius Nullius (nobody’s child) serves as an indispensable correlate to Terra Nullius (nobody’s land). By attending to the juridico-legal intricacies of capitalist social reproduction—a process that is inherently unstable and susceptible to sabotage—Goldstein gestures to the theoretical openings that allow us to imagine how things could be otherwise.

Parents gathered in support for the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) at a rally in South Dakota, 2013. Source: https://www.indianz.com/News/2013/03/29/native-sun-news-rally-in-suppo.asp[/caption] This talk resonated with Day’s by showing that the violent dispossession of Indigenous peoples is based on a denial of claims to both land and personhood. Indeed, for the colonizer, the legal doctrine of Fillius Nullius (nobody’s child) serves as an indispensable correlate to Terra Nullius (nobody’s land). By attending to the juridico-legal intricacies of capitalist social reproduction—a process that is inherently unstable and susceptible to sabotage—Goldstein gestures to the theoretical openings that allow us to imagine how things could be otherwise.